The cab let them off near the Arlington Bridge Equestrian Statues. Everything was beautiful: a classic winter wonderland, with pristine snow caked on tree limbs and statues. They walked to the Lincoln Memorial, approaching it from behind and keeping to the pathways, which had already been plowed—the National Park Service had its own snow-removal teams. Once there, they headed around to the front. The wooden platform and podium that had been set up for Jerrison’s speech, which they’d both seen on the news now, had been taken down. There was no obvious sign of where the president had been shot, but two young men were arguing on the steps about whether he’d been hit here or here. Jan thought that was a bit morbid, but still, she and Eric walked up the steps to look, too.

“I once went to Dealey Plaza,” Eric said.

Her face must have conveyed that he’d lost her. “In Dallas. Where Kennedy was shot.”

“Ah,” she said.

“There’s no commemorative plaque, no marker. But there is a white X painted on the roadway. If you wait for the light to turn red, you can go out into the middle of the street and stand on the spot where Oswald’s killing shot got him.”

The two people arguing about where Jerrison had been hit had come to an agreement. They took turns standing in the middle of one of the broad steps, each photographing the other. When they moved away, Jan and Eric walked to the same spot and gazed out at what, had the bullet taken a slightly altered trajectory, would have been the last sight Seth Jerrison had ever seen. Of course, it was different now: there were only a few dozen people around instead of the thousands who had been here for the speech, there was snow on the ground, and the sky was clear instead of the overcast it had been on Friday. But the Reflecting Pool stretched out in front of them, leading to the Washington Monument.

Unlike the boisterous pair who had preceded them in this spot, Eric and Jan stood in silence, but he did put his arm around her shoulders. When they’d had their fill, they walked up into the memorial and stared for a few minutes at the statue of the Great Emancipator. They then headed down the marble steps and started walking east. There were two paths they could take: along the south side of the Reflecting Pool or along the north; they opted for the north. A few other people were out strolling, and some joggers came toward them. They reached the World War II Memorial—which was Jan’s least favorite of the various war memorials; it was the most recently built, and the Vietnam and Korea ones were tough acts to follow. Then they headed up 17th Avenue to the corner of Constitution, and made their way around the gentle curve of Ellipse Road.

And there it was.

Or, more precisely, there it had been, on the other side of what was left of the metal fence.

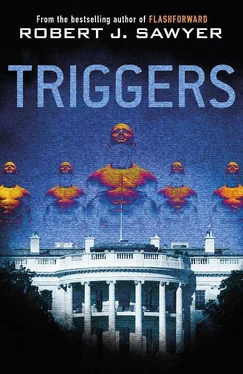

The White House.

Jan had seen pictures on the news, but that wasn’t the same as beholding the ruins in real life. She found herself shaking her head. Her breath, visible in the chill air, gave a faint reminder of the smoke that had been billowing from the ruins two days ago.

She looked at Eric to see if he wanted to go closer; he nodded.

Secretary of Defense Peter Muilenburg studied the giant display in the windowless room. The aircraft carriers were on station, or right on schedule to reach their stations. As he watched, the red digital timer changed from “1 day 0 hours 0 minutes” to “0 days 23 hours 59 minutes.” There was no seconds display, but his pulse, which he was feeling with a finger on his left radial artery, served well enough: he was the conductor for this orchestra, and his heartbeat the metronome.

It was hard to take his eyes off the destruction in front of him, but Eric Redekop turned to look at Janis. She was just thirty-two, for God’s sake—by the time she was his age, what crazy weapons would the world be facing? How small would they be? How much damage would they be able to do? It was almost inconceivable the amount of destructive power that would be in the hands of individuals by then.

The part of him that was anchored in the here and now had been worried about where this relationship might eventually lead—about whether he’d leave her a widow in her sixties.

The part of him that half—but only half—believed all the stuff he read in science magazines and medical journals had thought that surely they’d pass the tipping point sometime in the next couple of decades and the average human life span would increase by more than a year for every year that passed, meaning that he and Jan would both have much, much longer lives than their parents or grandparents, and that, as the decades, and maybe even centuries, rolled by, an eighteen-year age difference would seem utterly trivial.

But the part of him that came to the fore now was the one that had been lurking at the back of his mind since 9/11, and had been reinforced so many times since, including when the Sears Tower went down. Now that Jerrison was safe, and Eric finally had time to take it all in, he realized it didn’t matter what miracles future medical science might hold; the planet was fucked. The world had transitioned from a place where wars were fought between nations, declared in legislative assemblies and concluded with negotiated treaties, to a place where small cabals and even individuals could wreak havoc on a massive scale. And scale was indeed the issue: the weapons kept getting smaller, and the damage they were capable of kept getting larger.

And that meant that the age difference between him and Jan didn’t matter; none of it mattered. The world wasn’t going to last long enough for him to get really old or for Jan to collect a pension. It was over; they were done —it was only a matter of time before someone wrecked everything for everyone.

He looked at her lovely, youthful face—horrified though it was right now as it studied the caved-in ruins of what had been the home of the most powerful man in the world.

“Do you know who the Great Gazoo is?” he said.

She looked at him, tilting her head slightly in a way that made him think she was sifting memories, but whether the answer came from her own childhood or from Josh Latimer’s he had no way to tell. “A cartoon character,” she said. “From The Flintstones.”

He nodded. “He was from the planet Zetox,” he said, pleased, despite the circumstances, for knowing that bit of trivia. “Do you know why he was exiled to primitive Earth?”

She tilted her head again; he rather suspected that hardly anyone besides him remembered the answer to that—but he did; it had chilled him when it had first been explained in the episode in which Gazoo was introduced, and he’d never forgotten it.

The Great Gazoo—the smug little flying green guy whose introduction for so many indicated the point at which The Flintstones had jumped the shark—had been precisely the kind of terrorist Eric now feared the world would soon face. “He’d invented the ultimate weapon,” he said to Jan. “A button that if pressed would destroy the entire universe. So his people sent him somewhere with primitive technology so he could never build anything like that again.”

She looked at him, getting it. “But it doesn’t have to turn out that way,” she said.

He gestured at the White House: the central mansion reduced to blackened ruins, the east and west wings gutted by fire. “How else can it turn out?”

She let out a sigh. “I don’t know. But that can’t be the only way.”

Others had tarried here to look at the wreckage. A small knot of Japanese tourists was standing a short distance away, listening to a guide; Eric didn’t understand anything she was saying, but she sounded sad.

Читать дальше