“Really?” said Singh.

“Yes. I know all about what just went down between you and Private Adams.”

“Fascinating,” Singh said. “That means it wasn’t a dumping of memories—you didn’t just get a copy of my memories transferred to you when the power surge hit; you’re still somehow connected to me on an ongoing basis.” He frowned, clearly thinking about this.

“Anyway, it’s interesting what Private Adams said to you just now,” Susan said. She gestured to indicate it was all right for Singh to move closer to the president.

“Thank you,” Singh said, coming further into the room. “Mr. President, those gentlemen you recall playing basketball with: you said one of them was named Lamarr. Please think about him, and see if you can conjure up anything else about him.”

Seth’s eyebrows rose. “Oh. Um. Sure, Lamarr. Lamarr…um…” The president seemed to hesitate, then: “Lamarr Brown.”

“And his skin color?”

He took a moment to breathe, then. “He’s…oh, well, um, okay. Yes, he’s black. I’ve got a mental picture of him now, kind of. Black…short hair…gold earring…a scar above his right eye.”

“His right eye?”

“Sorry, my right; his left.”

“Private Adams described the same man, and added another detail. Something about Lamarr’s smile.”

The president frowned, concentrating. “Big gap between his two front teeth.” He paused. “But…but I don’t…I’ve never met…”

“No, you haven’t. And you don’t play basketball, either.” Singh tried to inject a little levity. “It’s not actually true that white men can’t jump, but you, a particular white man, can’t, because of your foot injury, isn’t that right?”

“Right.”

“And when you first recalled these men, you saw them as white,” said Singh. “Now you see them as black.”

“Um, yes.”

“My patient upstairs, as you’ve doubtless guessed, is African-American. And, unlike you, he knows all three of the gentlemen—who also are African-American.”

Seth said nothing.

Singh went on. “With due respect, Mr. President, let us not dance around the issue. If I ask you to picture a man—any man, an average man—you picture a white face, no doubt. It might interest you to know that a goodly number of African-Americans, not to mention Sikhs like myself, picture white faces, too: many of us are acutely aware that we are a minority in our neighborhoods and workplaces. Your default person is white, but my patient on the floor above grew up in South Central Los Angeles, an almost exclusively black community, and his default person is black.”

“So?” said the president, sounding, Susan thought, perhaps slightly uncomfortable.

“The point,” said Singh, “is that in storing memories of people, we store only how they differ from our default. You said one of the men was fat—and my patient described him the same way. But then you volunteered that the other two were thin, which might mean scrawny, which is why I asked you to clarify. If these people were notably thin, that detail might have been stored: scrawny is noteworthy; normal is not. Likewise, for my patient, his friends’ skin color was not noteworthy. And when you are reading his memories, all you have access to is what he’s actually stored: distinctive features, such as the gap between Lamarr’s teeth, or the scar above his eye, interesting items of clothing, and so on. And out of those paltry cues, your mind confabulated the rest of the image.”

“Confabulated?”

“Sorry, Mr. President. It means to fill in a gap in memory with a fabrication that the brain believes is true. See, people think that human memory is like computer memory: that somewhere in your head is a hard drive, or video recorder, or something, with a flawless, highly detailed record of everything you’ve seen and done. But that’s just not true. Rather, your brain stores a few details that will allow it to build a memory up when you try to recall it.”

“Okay,” Susan said, looking at Singh. “And you’re linked to this Lucius Jono fellow, right—and he might be the one linked to the president?”

“Yes.”

“What’s your most recent memory of him?”

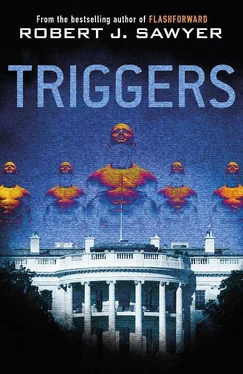

“It’s hard to say,” said Singh. “No, wait—wait. He is—or quite recently was—down in the cafeteria, eating…um, a bacon cheeseburger and onion rings.” He paused. “So that’s what bacon tastes like! Anyway, it’s got to be a recent memory; he’s talking about the destruction of the White House and the electromagnetic pulse.”

“All right,” said Susan. “I’m going to go speak to him. If we’re lucky, the circle only contains five people.”

The president said something, but Susan couldn’t make it out. She moved closer. “I’m sorry, sir?”

He tried again. “We haven’t had much luck so far today.”

She looked out the large windows and saw smoke in the sky. “No, sir, we haven’t.”

Secret Service agent Manny Cheung hadn’t recognized Gordon Danbury after his fall in the elevator shaft; it was, as the female agent who had first looked at his body on the roof of the elevator had said, not a pretty sight. But Danbury’s fingerprints had been intact, and running them had quickly turned up his identity. Cheung had known “Gordo”—as he was called—pretty well, or so he’d thought, although he’d never been to his house.

That was being rectified now. Although the Secret Service protected the president, it was the FBI that investigated attacks on him. But the two FBI agents dispatched to Danbury’s home had asked Cheung to join them since he’d been familiar with the deceased. Gordo lived an hour’s drive southwest of DC, in Fredericksburg, Virginia—far enough away that his place hadn’t been affected by the electromagnetic pulse.

It didn’t take long to find what they were looking for. Danbury had an old Gateway desktop computer, with a squarish matte-finish LCD monitor, an aspect ratio that was hard to get these days; both were connected to a UPS box. He’d left them on, with a Microsoft Word document open on the screen. The document said:

Mom,

You’ll never understand why I did this, I know, but it was the right thing. They won’t let me get away, but that doesn’t matter. I’m in heaven now, receiving my reward.

Praise be to God.

Cheung glanced around; there was no sign of a printer. “He expected to die today,” he said. “And he knew we’d find this.”

The FBI agents were both white, but one was stocky and the other thin. The stocky one said, “But he ran.”

“If he hadn’t, he’d have been gunned down,” said Cheung. “Sure, Gordo was a sharpshooter, but he’d have been facing a swarm of armed Secret Service agents; they’d have had no trouble taking him out, and he had to know that. Once he shot the president, he knew he’d be neutralized.”

“Did you know he was religious?” asked the thin FBI man, whose name was Smith, as he pointed at the glowing words.

“No,” said Cheung. “Never heard him mention it.”

“ ‘Praise be to God,’ ” Smith said. “Odd way to phrase it.”

Cheung frowned, then gestured at the computer. “May I?”

“Just a minute,” said the heavier agent, Kranz. He took a series of photos of the computer as they’d found it and dusted the keyboard for prints, on the off chance that the note hadn’t actually been typed up by Danbury.

“Okay,” Kranz said when he was done. “But don’t change or close the file.”

“No, no.” Cheung looked at the screen. The document name, showing in the title bar, was “Mom”—and since it had a name, he must have saved the file at least once. He brought up Word’s file menu, which listed recently opened documents at the bottom, and he noted which folder “Mom” was in. He then hit the Windows and E keys simultaneously to bring up Windows Explorer, navigated to that folder, and found “Backup of Mom.” “An older version of the file,” he said to the two FBI men, “prior to the last save.” He clicked on it, and it opened.

Читать дальше