Michael Cremo - Forbidden Archeology - The Hidden History of the Human Race

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Cremo - Forbidden Archeology - The Hidden History of the Human Race» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Torchlight Publishing, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race

- Автор:

- Издательство:Torchlight Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:9780892132942

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

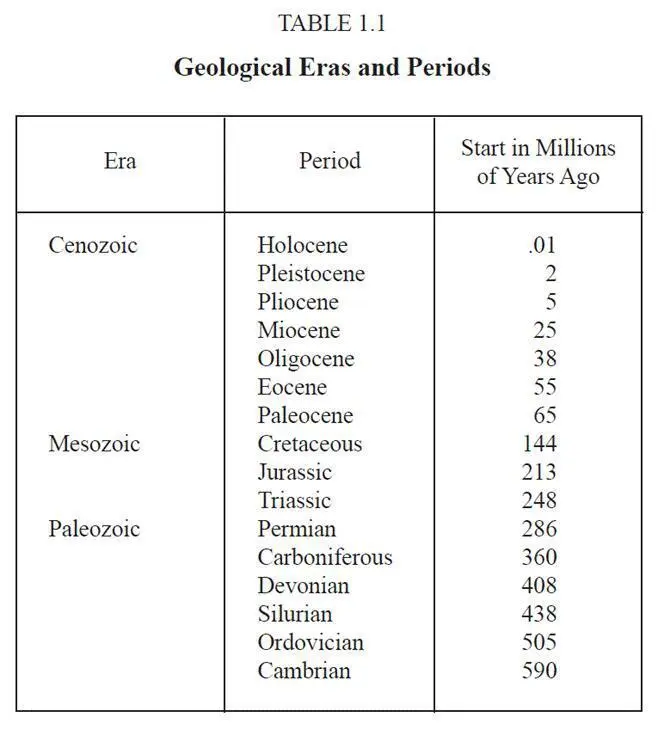

The geological time divisions were largely formulated in the nineteenth century, on the basis of stratigraphic considerations. Initially, there was no way to assign quantitative dates to these divisions, and thus geologists referred to them qualitatively—a particular period was simply said to be earlier or later than another. In the twentieth century, scientists began to assign quantitative dates by means of radiometric methods, and they have continued to revise these dates periodically up to the present time. Thus today many roughly equivalent systems of dates are used by different geologists and paleontologists.

In general, we will use the dates in Table 1.1 throughout this book. When authors from the nineteenth century or early twentieth century assign a fossil to, say, the Miocene period, we will state that the fossil is from 5 to 25 million years old. The author in question may have had no quantitative estimate of the age of his fossil, or he may have had an estimate quite different from 5 to 25 million years. However, if the modern dates from Table 1.1 are correct for the Miocene, and the early author correctly assigned his fossil to the Miocene on the basis of stratigraphy, then it is valid for us to use the modern dates. We will do this since it helps us compare the old discovery with modern discoveries, which are generally given quantitative radiometric dates.

In some cases, the geological periods assigned to certain strata in the nineteenth century have been revised by modern geologists. For example, some Miocene strata have been reassigned to the Pliocene period. In general, whenever strata in a given locality have been identified, we have tried to look up the periods assigned to them in current geological literature. We have then given dates to these strata on the basis of the modern period assignments.

However, this method is often inadequate for assigning dates to nineteenth century Pliocene and Pleistocene sites. In recent years, dates ranging from 2.7 to 15.0 million years have been assigned to the start of the Pliocene, with many vertebrate paleontologists favoring 10–12 million years. Other scientists have used the potassium-argon method to assign a date of 4.5–6.0 million years to the start of the Pliocene, and in Table 1.1 this date is listed as 5 million years (Berggren and Van Couvering 1974).

The Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary is defined as the base of the Calabrian, a marine stratigraphic subdivision from Italy, and this is now thought to be approximately 1.8 million years old. However, for this book the terrestrial mammalian fauna associated with the Pliocene and Pleistocene are of primary importance, since evidence pertaining to ancient human beings is typically dated on the basis of associated mammalian bones. A key faunal subdivision associated with the Pliocene and Pleistocene is the Villafranchian, which is divided into early, middle, and late sections, with dates ranging from 3.5 – 4.0 million years to 1.0 –1.3 million years. Since many vertebrate paleontologists assigned the Villafranchian entirely to the Pleistocene, the starting date of the Pleistocene was sometimes given as 3.5 – 4.0 million years. At present, however, the Villafranchian is divided between the Pleistocene and Pliocene, and the basal Calabrian date of 1.8–2.0 million years is assigned to the beginning of the Pleistocene (Berggren and Van Couvering 1974).

As a result, the best way to arrive at a quantitative date for a nineteenth century site with Villafranchian (or later) fauna is to refer to modern estimates for the age of that site in years, and we have tried to do this as much as possible.

For sites with pre-Villafranchian fauna, the period will be Early Pliocene or earlier, and it is adequate for the purposes of this book to arrive at a date using Table 1.1 and the period presently assigned to the site.

In this book, we will take the modern system for granted, accepting it, for the sake of argument, as a fixed reference frame to use in studying the history of ancient humans and near humans. However, it is clear on closer examination that this reference frame is by no means fixed, and it may be that further study will reveal as much ambiguity in the evidence for its different time divisions and fossil markers as we have found in the evidence for ancient humans.

Certainly, experts in geology have sometimes expressed dissatisfaction with the established geological time divisions. For example, Edmund m. Spieker (1956, p. 1803) made the following remarks in a lecture delivered to the American Association of Petroleum Geologists: “I wonder how many of us realize that the time scale was frozen in its present form by 1840. . . . How much world geology was known in 1840? A bit of Western Europe, none too well, and a lesser fringe of eastern North America. All of Asia, Africa, South America, and most of North America were virtually unknown. How dared the pioneers assume that their scale would fit the rocks in these vast areas, by far most of the world? Only in dogmatic assumption. . . . And in many parts of the world, notably India and South America, it does not fit. But even there it was applied! The founding fathers went forth across the earth and in Procrustean fashion made it fit the sections they found, even in places where the actual evidence literally proclaimed denial. So flexible and accommodating are the ‘facts’ of geology.”

1.8 The Appearance of the Hominids

The first apelike beings appeared in the Oligocene period, which began about 38 million years ago. The first apes thought to be on the line to humans appeared in the Miocene, which extends from 5 to 25 million years ago. These include the dryopithecine ape Proconsul africanus and Ramapithecus, which is now thought to be an ancestor of the orangutan.

Then came the Pliocene period. During the Pliocene, the first hominids, or erect-walking humanlike primates, are said to appear in the fossil record. The term hominid should be distinguished from hominoid, which designates the taxonomic superfamily including apes and humans. The earliest known hominid is Australopithecus , the “southern ape,” and is dated back as far as 4 million years, in the Pliocene.

This near human, say scientists, stood between 4 and 5 feet tall and had a cranial capacity of between 300 and 600 cubic centimeters (cc). From the neck down, Australopithecus is said to have been very similar to modern humans, whereas the head displayed some apelike and some human features.

One branch of Australopithecus, known as the “gracile” or lighter branch, is thought to have given rise to Homo habilis around 2 million years ago, at the beginning of the Pleistocene period. Homo habilis appears similar to Australopithecus except that his cranial capacity is said to have been larger, between 600 and 750 cc.

Homo habilis is thought to have given rise to Homo erectus (the species that includes Java man and Peking man) around 1.5 million years ago. Homo erectus is said to have stood between 5 and 6 feet tall and had a cranial capacity varying between 700 and 1,300 cc. most paleoanthropologists now believe that from the neck down, Homo erectus was, like Australopithecus and Homo habilis, almost the same as modern humans. The forehead, however, still sloped back from behind massive brow ridges, the jaws and teeth were large, and the lower jaw lacked a chin. It is believed that Homo erectus lived in Africa, Asia, and Europe until about 200,000 years ago.

Paleoanthropologists believe that anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ) emerged gradually from Homo erectus. Somewhere around 300,000 or 400,000 years ago the first early Homo sapiens or archaic Homo sapiens are said to have appeared. They are described as having a cranial capacity almost as large as that of modern humans, yet still manifesting to a lesser degree some of the characteristics of Homo erectus, such as the thick skull, receding forehead, and large brow ridges. Examples of this category are the finds from Swanscombe in England, Steinheim in Germany, and Fontechevade and Arago in France. Because these skulls also possess, to some degree, Neanderthal characteristics (Gowlett 1984, p. 85; Bräuer 1984, p. 328; stringer et al. 1984, p. 90), they are also classified as pre-Neanderthal types. Most authorities now postulate that both anatomically modern humans and the classic Western European Neanderthals evolved from the pre-Neanderthal or early Homo sapiens types of hominids (Spencer 1984, pp. 1– 49).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.