How much journaling do you have to do before you experience a measurable change? Quoting an article that appeared on March 2, 2009, on the Very Short List (VSL): Science website: 11

Twenty years ago, University of Texas psychologist James Pennebaker concluded that students who wrote about their most meaningful personal experiences for 15 minutes a day several days in a row felt better, had healthier blood work, and got higher grades in school. But a new study from the University of Missouri shows that a few minutes of writing will also suffice .

Researchers asked 49 college students to take two minutes on two consecutive days and write about something they found to be emotionally significant. The participants registered immediate improvements in mood and performed better on standardized measures of physiological well-being. An extended inward look isn’t necessary, the study concludes; merely “broaching the topic on one day and briefly exploring it the next” is enough to put things in perspective .

Four minutes can make a measurable difference. That exploding sound is the sound of my mind being blown.

One fun way of having a daily journaling practice is to write a different prompt on each piece of paper, put them all in a fishbowl (a dry one, I recommend), then pick out one or two at random each day. Here are some suggested prompts:

• What I am feeling now is…

• I am aware that…

• What motivates me is…

• I am inspired by…

• Today, I aspire to…

• What hurts me is…

• I wish…

• Others are…

• I made a happy mistake…

• Love is…

Here are instructions for the accurate self-assessment exercise. Notice that in addition to the usual journaling, we also added a primer to open your mind into a frame conducive to this exercise.

JOURNALING FOR SELF-ASSESSMENT

Prime

Before we begin journaling, let’s prime the mind.

Let’s spend 2 minutes thinking about one or more instances in which you responded positively to a challenging situation and the outcome was very satisfying to you. You felt you did great. If you are considering more than one instance, think about whether any connections or patterns are emerging.

Now, let’s take a moment to relax mentally.

(30-second pause) Journal

Prompts (2 minutes per prompt):

• Things that give me pleasure are…

• My strengths are…

Prime

Now let’s spend 2 minutes thinking about one or more instances in which you responded negatively to a challenging situation and the outcome was very unsatisfying to you. You felt that you performed badly, and you wish there were something you could change. If you are considering more than one instance, think about whether any connections or patterns are emerging.

Now, let’s take a moment to relax mentally.

(30-second pause) Journal

Prompts (2 minutes per prompt):

• Things that annoy me are…

• My weaknesses are…

Take a few minutes to read what you wrote to yourself.

My Emotions Are Not Me

As we deepen our self-awareness, we eventually arrive at a very important key insight: we are not our emotions.

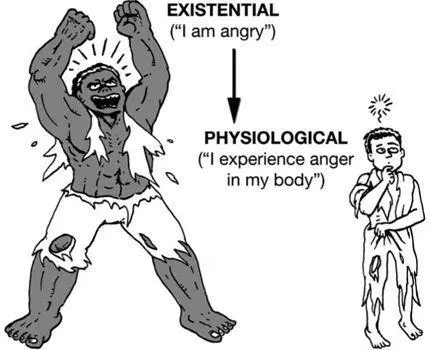

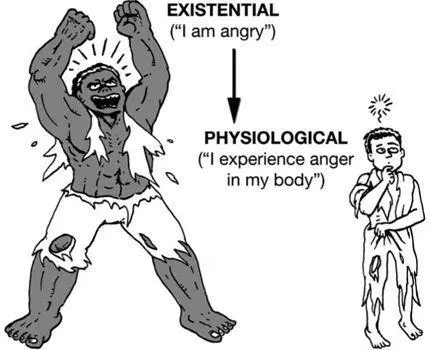

We usually think of our emotions as being us. This is reflected in the language we use to describe them. For example, we say, “I am angry” or “I am happy” or “I am sad,” as if anger, happiness, or sadness are us, or become who we are. To the mind, our emotions become our very existence.

With enough mindfulness practice, you may eventually notice a subtle but important shift—you may begin to feel that emotions are simply what you feel, not who you are. Emotions go from being existential (“I am”) to experiential (“I feel”). With even more mindfulness practice, there may be another subtle but important shift—you may begin to see emotions simply as physiological phenomena. Emotions become what we experience in the body, so we go from “I am angry” to “I experience anger in my body.”

This subtle shift is extremely important because it suggests the possibility of mastery over our emotions. If my emotions are who I am, then there is very little I can do about it. However, if emotions are simply what I experience in my body, then feeling angry becomes a lot like feeling pain in my shoulders after an extreme workout; both are just physiological experiences over which I have influence. I can soothe them. I can ignore them and go get some ice cream, knowing I will feel better in a few hours. I can experience them mindfully. Fundamentally, I can act on them because they are not my core being.

In meditative traditions, we have a beautiful metaphor for this insight. Thoughts and emotions are like clouds—some beautiful, some dark—while our core being is like the sky. Clouds are not the sky; they are phenomena in the sky that come and go. Similarly, thoughts and emotions are not who we are; they are simply phenomena in mind and body that come and go.

Possessing this insight, one creates the possibility of change within oneself.

CHAPTER FIVE

Riding Your Emotions like a Horse

Developing Self-Mastery

One can have no smaller or greater mastery than mastery of oneself.

—Leonardo da Vinci

The theme of this chapter can be summarized in these four words:

From Compulsion to Choice

Once upon a time in ancient China, a man on a horse rode past a man standing on the side of the road. The standing man asked, “Rider, where are you going?” The man on the horse answered, “I don’t know. Ask the horse.”

This story provides a metaphor for our emotional lives. The horse represents our emotions. We usually feel compelled by our emotions. We feel we have no control over the horse, and we let it take us wherever it wants to. Fortunately, it turns out that we can tame and guide the horse. It begins with understanding the horse and observing its preferences, tendencies, and behaviors. Once we understand the horse, we learn to communicate and work with it skillfully. Eventually, it takes us wherever we want to go. Hence we create choice for ourselves. We can then choose to ride into the sunset and look cool like John Wayne.

The last chapter, when we explored self-awareness, is about understanding the horse. In this chapter, we will make use of self-awareness to gain mastery over our emotions. In other words, we will learn to ride the horse.

About Self-Regulation

When we think of self-regulation, we usually think only of self-control, like the not-screaming-at-the-CEO type of self-control. If that is all you are thinking, my friends, you are missing all the good, yummy stuff. Self-regulation goes far beyond self-control. Daniel Goleman identifies five emotional competencies under the domain of self-regulation:

1. Self-control: Keeping disruptive emotions and impulses in check

2. Trustworthiness: Maintaining standards of honesty and integrity

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![Chade-Meng Tan - Search Inside Yourself - Increase Productivity, Creativity and Happiness [ePub edition]](/books/703803/chade-thumb.webp)