Various - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Various - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Издательство: Иностранный паблик, Жанр: periodic, foreign_edu, Путешествия и география, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848

- Автор:

- Издательство:Иностранный паблик

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Let us have peace with the French by all means, and with all the world beside; but let us not fall into the despicable and stupid blunder of supposing that human passion and human prejudice, the lust for power, and the cravings of ambition, can ever be eradicated by any system of commercial arrangement. Britain is naturally an object of envy to all the continental states. It is her strength and position which have hitherto maintained the balance of power – and of that the European states are fully and painfully aware. Every step which can tend to weaken the fidelity of her colonies, is regarded with intense interest abroad, and more especially in France. The people of that country envy us for our wealth, and dislike us for our power; and war with Britain, could the French afford it, would at any time find a host of advocates. We are not believers in the probability of such an event, if we keep ourselves reasonably prepared; but the very first relaxation upon our part would inevitably tend to accelerate it. It is quite possible that France may yet have to undergo another dynastic convulsion. The death of Louis Philippe may be the signal for intestine disorder. The Count of Paris is a mere boy, and popularity is not on the side of his uncle and guardian. A powerful party still exists, acknowledging no king save the rightful heir of St Louis; and the fanatical republican section is still strong and virulent. These are things which it would be imprudent to disregard, and of which no man living can venture to predict the result. The death of the Queen of Spain would, according to all appearances, give rise to a rupture with France, and possibly test, within a shorter period than we could have believed, the sufficiency of our national defences. There is at this moment every reason why our real strength and power should be made apparent to the world, and our weakness, where it does exist, immediately remedied and repaired.

Had the Duke of Wellington proposed, like Friar Bacon in Greene's old play,

the outcry could not have been greater. An iron wall might perhaps have been rather popular in the mining districts. But his Grace proposes no such thing. He only suggests the propriety of a small augmentation of the regular forces at home, the strengthening of our neglected fortifications, and the gradual reimbodiment of the militia. It is for the British nation, or rather its representatives, to adopt or reject the proposal. Now, it is worth while that we should keep in mind what is our actual disposable force at present.

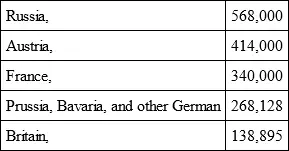

According to the most recent authorities, the armies of the principal European powers would rank as follows:

The disproportion of force exhibited by this list is sufficiently obvious; but when we descend to particulars, it will in reality be found much greater. Abroad, the majority of the male population are trained to the use of arms: with us it is notoriously the reverse. France, in the course of one week, could materially increase the amount of her regular army; whilst here that would be obviously impossible. Beyond Algeria, France has almost no colonies as stations for her standing force. We have to provide for the East and West Indies, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Cape, Ceylon, Hong Kong, the Mauritius, Gibraltar, Malta, the Ionian Islands, and others. The profession of the British soldier is any thing but a sinecure. A great portion of his life must be spent abroad; he may be called upon to undergo the most rapid vicissitudes of climate, to pass from one hemisphere to another in the discharge of his anxious duty. There is no service in the world more trying or severe; and it very ill becomes Mr Cobden, or any of his class, to sneer at that establishment, which is kept up for the direct promotion of our commerce. So large a portion of the territorial surface of the world is nowhere defended at so little cost either of money or of men. Indeed, as recent events have shown, we are but too apt to save the one at the expense of the other. No doubt, if the free-trade policy is carried out to the uttermost – if our colonies are to be thrown away as useless, and our foreign stations dismantled, we might submit to a still further reduction. France will be too happy to receive Gibraltar or Malta from our hands, and will cheerfully free us from the expense of maintaining garrisons there. Let us but make over to that affectionate and domesticated people the keys of the Mediterranean, and we shall soon see with what eagerness they will co-operate in the dissemination of Mr Cobden's free-trade dogmas.

Apart from the colonies, we have a serious difficulty at home. Ireland – that most wretched and ungrateful country, which no experience can improve – is as far from tranquillity as ever. The hard-working population of Britain submitted last year without a murmur to an exorbitant taxation, for the purpose of relieving the distress occasioned by the failure of the potato crop. The return is a howl of defiance from the brutal demagogue, and an immediate increase of murder and of crime. Notwithstanding every kind of remedial measure – notwithstanding their exemption, which is an injustice to us, from many of the heaviest burdens of the state – notwithstanding the mistaken policy which fostered their institutions and their schools, the Roman Catholics of Ireland stand out in bad pre-eminence, as the most cold-blooded, unthankful, and cowardly assassins of the world. In order to repress that outrage, which is so villanously rife among them, and which nothing but physical force can restrain from breaking out into open rebellion, we are compelled at all times to keep the largest portion of our remanent disposable force quartered in Ireland. The consequence is, that a mere handful of our standing army is left in Great Britain.

If Mr Cobden should like to see a little terrestrial paradise, in which few birds, with that gaudy plumage which is so offensive to his eyes, can be found, he had better come down to Scotland, and pay us another visit. He is kind enough, we observe, to make himself the mouthpiece of our sentiments upon this matter of the defences; and, certainly, if there be any truth in the adage that we are entitled at least to see what we are paying for, Scotland has no reason to be peculiarly warlike in her sentiments. Mr Cobden will find us quite as affectionate and domesticated a people as the French; and he may rely upon it, that he will not be shocked by any over-blaze of scarlet. From a turbulent, we have gradually settled down to be a quiet race; and as a natural consequence, we share in none of those benefits which are heaped so liberally upon the "persecuted Irish." Our only excitements are a Church squabble, which does not require the interference of the military, but exhausts itself in the public prints; or a bread row, which is always over, long before a detachment can be brought from the nearest station, it may be at the distance of some hundred miles. We are never noticed in Parliament, except to be praised for our good behaviour, or to have some remaining fragment of our national establishments reduced. We pay for an army and a navy which we never see; indeed, of late years the French and Danish flags have been far more frequently displayed upon our coasts than the broad pendant of Great Britain. In many of our counties a soldier is an unknown rarity; and the only drum that has been heard for the last thirty years, is in the peaceable possession of the town-crier. England, we apprehend, except in the immediate neighbourhood of the metropolis and of Manchester, is not much better supplied: in short, so far as Britain is concerned, we have a remarkably insufficient force, and one which has been declared by the highest military authority alive, wholly incompetent for our protection in the case of an attempted invasion. Cobden, who has no veneration for successful warriors, having feathered his nest very pleasantly otherwise, admits that he has not the slightest practical knowledge of the trade of war. We therefore demur to his position that this is a question for civilians to determine, and that military and naval men have nothing to do with it. His previous admission involves an inconsistency. He might as well say, that, having no acquaintance whatever with engineering, he is entitled to deliver his opinions in opposition to Walker or Stephenson, on the construction of a skew bridge, or the practicability of boring a tunnel. If one of those vessels in the Tagus, which, according to Cobden, are kept there for the sole purpose of instructing our seamen in the culture of the geranium, was to spring a leak, we should assuredly apply to Jack Chips, the carpenter, to stop it, before invoking the aid of the peripatetic apostle of free-trade. And just so is it with the state of our national defences. Manchester must excuse us, if we prefer the testimony of the Duke of Wellington upon this point to the more dubious experiences of Cobden. It is, of course, quite another question, whether the leak shall be stopped, or the vessel permitted to founder peaceably. Mr Cobden may be heard upon that point, under special reference to the magnitude of the stake which he hazards, but we decline receiving his opinion on the subject of military fortifications. He can no more pronounce a judgement on the adequate state of our defences, than he can parse a paragraph of Xenophon; and therefore, by approaching the subject, he has been guilty of presumption and impertinence.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.