Various - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Various - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Издательство: Иностранный паблик, Жанр: periodic, foreign_edu, Путешествия и география, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849

- Автор:

- Издательство:Иностранный паблик

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Variety affects appearance and quality; and how these are to be consulted in reference to the market in which the grain is to be sold, may be gathered from the following: —

"When wheat is quite opaque, indicating not the least translucency, it is in the best state for yielding the finest flour – such flour as confectioners use for pastry; and in this state it will be eagerly purchased by them at a large price. Wheat in this state contains the largest proportion of fecula or starch, and is therefore best suited to the starch-maker, as well as the confectioner. On the other hand, when wheat is translucent, hard, and flinty, it is better suited to the common baker than the confectioner and starch manufacturer, as affording what is called strong flour, that rises boldly with yeast into a spongy dough. Bakers will, therefore, give more for good wheat in this state than in the opaque; but for bread of finest quality the flour should be fine as well as strong, and therefore a mixture of the two conditions of wheat is best suited for making the best quality of bread. Bakers, when they purchase their own wheat, are in the habit of mixing wheat which respectively possesses those qualities; and millers who are in the habit of supplying bakers with flour, mix different kinds of wheat, and grind them together for their use. Some sorts of wheat naturally possess both these properties, and on that account are great favourites with bakers, though not so with confectioners; and, I presume, to this mixed property is to be ascribed the great and lasting popularity which Hunter's white wheat has so long enjoyed. We hear also of ' high mixed ' Danzig wheat, which has been so mixed for the purpose, and is in high repute amongst bakers. Generally speaking, the purest coloured white wheat indicates most opacity, and, of course, yields the finest flour; and red wheat is most flinty, and therefore yields the strongest flour: a translucent red wheat will yield stronger flour than a translucent white wheat, and yet a red wheat never realises so high a price in the market as white – partly because it contains a larger proportion of refuse in the grinding, but chiefly because it yields less fine flour, that is, starch."

In regard to wheat, it has been supposed, that the qualities referred to in the above extract, as especially fitting certain varieties for the use of the confectioner, &c., were owing to the existence of a larger quantity of gluten in these kinds of grain. Chemical inquiry has, however, nearly dissipated that idea, and with it certain erroneous opinions, previously entertained, as to their superior nutritive value. Climate and physiological constitution induce differences in our vegetable productions, which chemical research may detect and explain, but may never be able to remove or entirely control.

The bran, or external covering of the grain of wheat, has recently also been the subject of scientific and economical investigation. It has been proved, by the researches of Johnston, confirmed by those of Miller and others, that the bran of wheat, though less readily digestible, contains more nutritive matter than the white interior of the grain. Brown, or household bread, therefore, which contains a portion of the bran, is to be preferred, both for economy and for nutritive quality, to that made of the finest flour.

Upon the economy of mixing potato with wheaten flour, and of home-made bread, Mr Stephens has the following: —

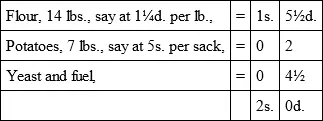

"It is assumed by some people, that a mixture of potatoes amongst wheaten flour renders bread lighter and more wholesome. That it will make bread whiter, I have no doubt; but I have as little doubt that it will render it more insipid, and it is demonstrable that it makes it dearer than wheaten flour. Thus, take a bushel of 'seconds' flour, weighing 56 lbs. at 5s. 6d. A batch of bread, to consist of 21 lbs., will absorb as much water, and require as much yeast and salt, as will yield 7 loaves, of 4 lbs. each, for 2s. 4d., or 4d. per loaf. 'If, instead of 7 lbs. of the flour, the same weight of raw potatoes be substituted, with the hope of saving by the comparatively low price of the latter article, the quantity of bread that will be yielded will be but a trifle more than would have been produced from 14 lbs. of flour only , without the addition of the 7 lbs. of potatoes; for the starch of this root is the only nutritive part, and we have proved that but one-seventh or one-eighth of it is contained in every pound, the remainder being water and innutritive matter. Only 20 lbs. of bread, therefore, instead of 28 lbs., will be obtained; and this, though white, will be comparatively flavourless, and liable to become dry and sour in a few days; whereas, without the latter addition, bread made in private families will keep well for 3 weeks, though, after a fortnight, it begins to deteriorate, especially in the autumn.' The calculation of comparative cost is thus shown: —

The yield, 20 lbs., or 5 loaves of 4 lbs. each, will be nearly 5d. each, which is dearer than the wheaten loaves at 4d. each, and the bread, besides, of inferior quality.

"'There are persons who assert – for we have heard them – that there is no economy in baking at home. An accurate and constant attention to the matter, with a close calculation of every week's results for several years – a calculation induced by the sheer love of investigation and experiment – enables us to assure our readers, that a gain is invariably made of from 1½d. to 2d. on the 4 lb. loaf. If all be intrusted to servants, we do not pretend to deny that the waste may neutralise the profit ; but, with care and investigation, we pledge our veracity that the saving will prove to be considerable.' These are the observations of a lady well known to me."

In the natural history of barley the most remarkable fact is, the high northern latitudes in which it can be successfully cultivated. Not only does it ripen in the Orkney and Shetland and Faroe Islands, but on the shores of the White Sea; and near the North Cape, in north latitude 70°, it thrives and yields nourishment to the inhabitants. In Iceland, in latitude 63° to 66° north, it ceases to ripen, not because the temperature is too low, but because rains fall at an unseasonable time, and thus prevent the filling ear from arriving at maturity.

The oat is distinguished by its remarkable nutritive quality, compared with our other cultivated grains. This has been long known in practice in the northern parts of the island, where it has for ages formed the staple food of the mass of the population, though it was doubted and disputed in the south so much, as almost to render the Scotch ashamed of their national food. Chemistry has recently, however, set the matter at rest, and is gradually bringing oatmeal again into general favour. We believe that the robust health of many fine families of children now fed upon it, in preference to wheaten flour, is a debt they owe, and we trust will not hereafter forget, to chemical science.

On oatmeal Mr Stephens gives us the following information: —

"The portion of the oat crop consumed by man is manufactured into meal . It is never called flour, as the millstones are not set so close in grinding it as when wheat is ground, nor are the stones for grinding oats made of the same material, but most frequently only of sandstone – the old red sandstone or greywacke. Oats, unlike wheat, are always kiln-dried before being ground; and they undergo this process for the purpose of causing the thick husk, in which the substance of the grain is enveloped, to be the more easily ground off, which it is by the stones being set wide asunder; and the husk is blown away, on being winnowed by the fanner, and the grain retained, which is then called groats . The groats are ground by the stones closer set, and yield the meal. The meal is then passed through sieves, to separate the thin husk from the meal. The meal is made in two states: one fine , which is the state best adapted for making into bread, in the form called oat-cake or bannocks; and the other is coarser or rounder ground, and is in the best state for making the common food of the country people – porridge, Scottice , parritch. A difference of custom prevails in respect to the use of these two different states of oatmeal, in different parts of the country, the fine meal being best liked for all purposes in the northern, and the round or coarse meal in the southern counties; but as oat-cake is chiefly eaten in the north, the meal is there made to suit the purpose of bread rather than of porridge; whereas, in the south, bread is made from another grain, and oatmeal is there used only as porridge. There is no doubt that the round meal makes the best porridge, when properly made – that is, seasoned with salt, and boiled as long as to allow the particles to swell and burst, when the porridge becomes a pultaceous mass. So made, with rich milk or cream, few more wholesome dishes can be partaken by any man, or upon which a harder day's work can be wrought. Children of all ranks in Scotland are brought up on this diet, verifying the poet's assertion —

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.