Various - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Various - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Издательство: Иностранный паблик, Жанр: periodic, foreign_edu, Путешествия и география, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851

- Автор:

- Издательство:Иностранный паблик

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

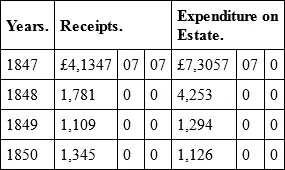

Price of the Estate, £163,779.

– Inverness Courier.

Couple this with the facts that, in 1850, in the face of average prices of wheat at about 40s. a quarter, the importation of all sorts of grain into Great Britain and Ireland was about 9,500,000 quarters – of course displacing domestic industry employed previous to 1846 in this production; so that the acres under wheat cultivation in Ireland have sunk from 1,048,000 in 1847, to 664,000 in 1849; and there will be no difficulty in explaining the immense influx of the destitute from the country into the great towns – augmenting thus the enormous mass of destitution, pauperism, and wretchedness, with which they are already overwhelmed.

Such is a picture, however brief and imperfect, of the social condition of our population, after twenty years of Liberal government, self-direction, and increasing popularisation, enhanced, during the last five years, by the blessings of Free Trade and a restricted and fluctuating currency. The question remains the most momentous on which public attention can now be engaged. Is this state of things unavoidable , or are there any means by which, under Providence, it may be removed or alleviated? Part of it is unavoidable, and by no human wisdom could be averted. But by far the greater part is directly owing to the selfish and shortsighted legislation of man, and might at once be removed by a wise, just, and equal system of government.

There is an unavoidable tendency, in all old and wealthy states, for riches to concentrate in the highest ranks, and numbers to become excessive in the lowest. This arises from the different set of principles which, at the opposite ends of the chain of society, regulate human conduct in the direction of life. Prudence, and the desire of elevation, are predominant at the one extremity; recklessness, and the thirst for gratification, at the other. Life is spent in the one in striving to gain, and endeavouring to rise; in the other, in seeking indulgence, and struggling with its consequences. Marriage is contracted in the former, generally speaking, from prudential or ambitious motives; in the latter, from the influence of passion, or the necessity of a home. In the former, fortune marries fortune, or rank is allied to rank; in the latter, poverty is linked to poverty, and destitution engenders destitution. These opposite set of principles come, in the progress of time, to exercise a great and decisive influence on the comparative numbers and circumstances of the affluent and the destitute classes. The former can rarely, if ever, maintain their own numbers; the latter are constantly increasing in numbers, with scarcely any other limit on their multiplication but the experienced impossibility of rearing a family. Fortunes run into fortunes by intermarriage, the effects of continued saving, and the dying out of the direct line of descendants among the rich. Poverty is allied to poverty by the recklessness invariably produced by destitution among the poor. Hence the rich, in an old and wealthy community, have a tendency to get richer, and the poor poorer; and the increase of wealth only increases this tendency, and renders it more decided with every addition made to the national fortunes. This tendency is altogether irrespective of primogeniture, entails, or any other device to retain property in a particular class of society. It exists as strongly in the mercantile class, whose fortunes are for the most part equally divided, as in the landed, where the estate descends in general to the eldest son; and was as conspicuous in former days in Imperial Rome, when primogeniture was unknown, and is now complained of as as great a grievance in Republican France, where the portions of children are fixed by law, as it is in Great Britain, where the feudal institutions still prevail among those connected with real estates.

In the next place, this tendency in old and opulent communities has been much enhanced, in the case of Great Britain, by the extraordinary combination of circumstances – some natural, some political – which have, in a very great degree, augmented its manufacturing and commercial industry. It would appear to be a general law of nature, in the application of which the progress of society makes no or very little change – that machinery and the division of labour can add scarcely anything to the powers of human industry in the cultivation of the soil – but that they can work prodigies in the manufactories or trades which minister to human luxury or enjoyment. The proof of this is decisive. England, grey in years, and overloaded with debt, can undersell the inhabitants of Hindostan in cotton manufactures, formed in Manchester out of cotton grown on the banks of the Ganges or the Mississippi; but she is undersold in grain, and to a ruinous extent, by the Polish or American cultivators, with grain raised on the banks of the Vistula or the Ohio. It is the steam-engine and the division of labour which have worked this prodigy. They enable a girl or a child, with the aid of machinery, to do the work of a hundred men. They substitute the inanimate spindle for human hands. But there is no steam-engine in agriculture. The spade and the hoe are its spindles, and they must be worked by human hands. Garden cultivation, exclusively done by man, is the perfection of husbandry. By a lasting law of nature, the first and best employment of man is reserved, and for ever reserved, for the human race. Thus it could not be avoided that in Great Britain, so advantageously situated for foreign commerce, possessing the elements of great naval strength in its forests, and the materials in the bowels of the earth from which manufacturing greatness was to arise, should come, in process of time, to find its manufacturing bear an extraordinary and scarce paralleled proportion to its agricultural population.

Consequent on this was another circumstance, scarcely less important in its effects than the former, which materially enhanced the tendency to excess of numbers in the manufacturing portions of the community. This was the encouragement given to the employment of women and children in preference to men in most manufacturing establishments – partly from the greater cheapness of their labour, partly from their being better adapted than the latter for many of the operations connected with machines, and partly from their being more manageable, and less addicted to strikes and other violent insurrections, for the purpose of forcing up wages. Great is the effect of this tendency, which daily becomes more marked as prices decline, competition increases, and political associations among workmen become more frequent and formidable by the general popularising of institutions. The steam-engine thus is generally found to be the sole moving power in factories; spindles and spinning-jennies the hands by which their work is performed; women and children the attendants on their labour. There is no doubt that this precocious forcing of youth, and general employment of young women in factories, is often a great resource to families in indigent circumstances, and enables the children and young women of the poor to bring in, early in life, as much as enables their parents, without privation, often to live in idleness. But what effect must it have upon the principle of population, and the vital point for the welfare of the working-classes – the proportion between the demand for and the supply of labour? When young children of either sex are sure, in ordinary circumstances, of finding employment in factories, what an extraordinary impulse is given to population around them, under circumstances when the lasting demand for labour in society cannot find them employment! The boys and girls find employment in the factories for six or eight years; so far all is well: but what comes of these boys and girls when they become men and women, fathers and mothers of children, legitimate and illegitimate, and their place in the factories is filled by a new race of infants and girls, destined in a few years more to be supplanted, in their turn, by a similar inroad of juvenile and precocious labour? It is evident that this is an important and alarming feature in manufacturing communities; and, where they have existed long, and are widely extended, it has a tendency to induce, after a time, an alarming disproportion between the demand for, and the supply of full-grown labour over the entire community. And to this we are in a great degree to ascribe the singular fact, so well and painfully known to all persons practically acquainted with such localities, that while manufacturing towns are the places where the greatest market exists for juvenile or infant labour – to obtain which the poor flock from all quarters with ceaseless alacrity – they are at the same time the places where destitution in general prevails to the greatest and most distressing extent, and it is most difficult for full-grown men and women to obtain permanent situations or wages, on which they can maintain themselves in comfort. Their only resource, often, is to trust, in their turn, to the employment of their children for the wages necessary to support the family. Juvenile labour becomes profitable – a family is not felt as a burden, but rather as an advantage at first ; and a forced and unnatural impulse is given to population by the very circumstances, in the community, which are abridging the means of desirable subsistence to the persons brought into existence.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.