Various - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Various - Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Издательство: Иностранный паблик, Жанр: periodic, foreign_edu, Путешествия и география, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849

- Автор:

- Издательство:Иностранный паблик

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

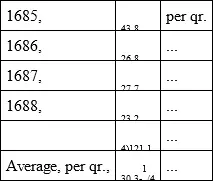

In corroboration of this view, if so eminent an authority as Adam Smith requires any corroboration, we subjoin the market prices of wheat at Oxford for the four years of James's reign. The averages are struck from the highest and lowest prices calculated at Lady-day and Michaelmas.

But the Oxford returns are always higher than those of Mark Lane, which latter again are above the average of the whole country. So that, in forming an estimate from such data, of the general price over England, we may be fairly entitled to deduct two shillings a quarter, which will give a result closely approximating to that of Gregory King. We may add, that this calculation was approved of and repeated by Dr Davenant, who is admitted even by Mr Macaulay to be a competent authority.

Keeping the above facts in view, let us attend to Mr Doubleday's statement of the condition of the working men, in those despotic days, when national debts were unknown. It is diametrically opposed in every respect to that of Mr Macaulay: and, from the character and research of the writer, is well entitled to examination: —

"The condition of the working classes was proportionably happy. Their wages were good, and their means far above want, where common prudence was joined to ordinary strength. In the towns the dwellings were cramped, by most of the towns being walled; but in the country, the labourers were mostly the owners of their own cottages and gardens, which studded the edges of the common lands that were appended to every township. The working classes, as well as the richer people, kept all the church festivals, saints' days, and holidays. Good Friday, Easter and its week, Whitsuntide, Shrove Tuesday, Ascension-day, Christmas, &c., were all religiously observed. On every festival, good fare abounded from the palace to the cottage; and the poorest wore strong broad-cloth and homespun linen, compared with which the flimsy fabrics of these times are mere worthless gossamers and cobwebs, whether strength or value be looked at. At this time, all the rural population brewed their own beer, which, except on fast-days, was the ordinary beverage of the working man. Flesh meat was commonly eaten by all classes. The potato was little cultivated; oatmeal was hardly used; even bread was neglected where wheat was not ordinarily grown, though wheaten bread (contrary to what is sometimes asserted) was generally consumed. In 1760, a later date, when George III. began to reign, it was computed that the whole people of England (alone) amounted to six millions. Of these, three millions seven hundred and fifty thousand were believed to eat wheaten bread; seven hundred and thirty-nine thousand were computed to use barley bread; eight hundred and eighty-eight thousand, rye bread; and six hundred and twenty-three thousand, oatmeal and oat-cakes. All, however, ate bacon or mutton, and drank beer and cider; tea and coffee being then principally consumed by the middle classes. The very diseases attending this full mode of living were an evidence of the state of national comfort prevailing. Surfeit, apoplexy, scrofula, gout, piles, and hepatitis; agues of all sorts, from the want of drainage; and malignant fevers in the walled towns, from want of ventilation, were the ordinary complaints. But consumption in all its forms, marasmus and atrophy, owing to the better living and clothing, were comparatively unfrequent: and the types of fever, which are caused by want, equally so."

We shall fairly confess that we have been much confounded by the dissimilarity of the two pictures; for they probably furnish the strongest instance on record of two historians flatly contradicting each other. The worst of the matter is, that we have in reality few authentic data which can enable us to decide between them. So long as Gregory King speaks to broad facts and prices, he is, we think, accurate enough; but whenever he gives way, as he does exceedingly often, to his speculative and calculating vein, we dare not trust him. For example, he has entered into an elaborate computation of the probable increase of the people of England in succeeding years, and, after a show of figures which might excite envy in the breast of the Editor of The Economist , he demonstrates that the population in the year 1900 cannot exceed 7,350,000 souls. With half a century to run, England has already more than doubled the prescribed number. Now, though King certainly does attempt to frame an estimate of the number of those who, in his time, did not indulge in butcher meat more than once a week, we cannot trust an assertion which was, in point of fact, neither more nor less than a wide guess; but we may, with perfect safety, accept his prices of provisions, which show that high living was clearly within the reach of the very poorest. Beef sold then at 1 1/ 3d., and mutton at 2- 1/ 4d. per lb.; so that the taste of those viands must have been tolerably well known to the hundreds of thousands of families whom Mr Macaulay has condemned to the coarsest farinaceous diet.

It is unfortunate that we have no clear evidence as to the poor-rates, which can aid us in elucidating this matter. Mr Macaulay, speaking of that impost, says, "It was computed, in the reign of Charles II., at near seven hundred thousand pounds a-year, much more than the produce either of the excise or the customs, and little less than half the entire revenue of the crown. The poor-rate went on increasing rapidly , and appears to have risen in a short time to between eight and nine hundred thousand a-year – that is to say, to one-sixth of what it now is. The population was then less than one-third of what it now is." This view may be correct, but it is certainly not borne out by Mr Porter, who says that, "so recently as the reign of George II., the amount raised within the year for poor-rates and county-rates in England and Wales, was only £730,000. This was the average amount collected in the years 1748, 1749, 1750." To establish anything like a rapid increase, we must assume a much lower figure than that from which Mr Macaulay starts. A rise of £30,000 in some sixty years is no remarkable addition. Mr Doubleday, as we have seen, estimates the amount of the rate at only £300,000.

But even granting that the poor-rate was considered high in the days of James, it bore no proportion to the existing population such as that of the present impost. The population of England has trebled since then, and we have seen the poor-rates rise to the enormous sum of seven millions. Surely that is no token of the superior comfort of our people. We shall not do more than allude to another topic, which, however, might well bear amplification. It is beyond all doubt, that, before the Revolution, the agricultural labourer was the free master of his house and garden, and had, moreover, rights of pasturage and commonty, all which have long ago disappeared. The lesser freeholds, also, have been in a great measure absorbed. When a great national poet put the following lines into the mouth of one of his characters, —

"Even therefore grieve I for those yeomen,

England's peculiar and appropriate sons,

Known in no other land. Each boasts his hearth

And field as free, as the best lord his barony,

Owing subjection to no human vassalage,

Save to their king and law. Hence are they resolute,

Leading the van on every day of battle,

As men who know the blessings they defend;

Hence are they frank and generous in peace,

As men who have their portion in its plenty.

No other kingdom shows such worth and happiness

Veiled in such low estate – therefore I mourn them,"

we doubt not that he intended to refer to the virtual extirpation of a race, which has long ago been compelled to part with its birthright, in order to satisfy the demands of inexorable Mammon. Even whilst we are writing, a strong and unexpected corroboration of the correctness of our views has appeared in the public prints. Towards the commencement of the present month, November, a deputation from the agricultural labourers of Wiltshire waited upon the Hon. Sidney Herbert, to represent the misery of their present condition. Their wages, they said, were from six to seven shillings a-week, and they asked, with much reason, how, upon such a pittance, they could be expected to maintain their families. This is precisely the same amount of nominal wage which Mr Macaulay assigns to the labourer of the time of King James. But, in order to equalise the values, we must add a third more to the latter, which is at once decisive of the question. Perhaps Mr Macaulay, in a future edition, will condescend to explain how it is possible that the labourer of our times can be in a better condition than his ancestor, seeing that the price of wheat is nearly doubled, and that of butcher-meat fully quadrupled? We are content to take his own authorities, King and Davenant, as to prices; and the results are now before the reader.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 66, No. 410, December 1849» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.