Kelly thought the tragedy of love wasn’t that we weren’t loved but that we weren’t loved by the people we’d been given. The problem with seeking revenge was that if he couldn’t find the one he was seeking, then who might get hurt instead.

One night, Kelly parked the truck down the street from the green house, the only lit rooms for blocks. In the darkness it would be harder to see out the windows than to see in, and from the far edge of the yard he watched the mother setting the table for a dinner for three. The mother’s car was in the driveway but the brother’s was gone and Kelly wondered who she was expecting, the older son or the husband. When no one else came he watched from the dark as she called the boy in to dinner, as the boy sat down in the bright room and ate his food silently, eyes cast to the task. The mother’s mouth moved but what was she saying. If she was asking questions the boy didn’t answer.

Kelly flexed his muscles, hopped from foot to foot to keep warm in the black and lightless air. He was starting to get his step back, remembering how to keep his torso and his head in a constant bob, an unpredictable weave. The painter with the big hands had taught him to fight by never taking the same step twice but Kelly thought a better tactic was to broadcast his every intention and still come out ahead. For now he was making a case. He was glad the boy came to visit. He thought no matter how long he spent with the boy he would never want to hurt him. He was aware of what lurked within and he had made moves to cordon that action from thought, present want. He would stretch his life beyond the mistakes of his past, and for this the boy was both the test and the answer.

W

The gym posted its rules on every wall. There was a maximum number of times you were allowed to spar in a week but no one kept close count. Most of the others sparred at sixty or eighty percent of full speed but if they held back against him he surged into the space of their hesitance. His head snapped back under jab after jab; in the locker-room mirror, his belly and ribs looked punched in, bruises sprawled over scrawny skin. He wasn’t eating again or when he ate he didn’t eat right. He was stronger than he looked but he wasn’t strong enough. His was a musculature fit for climbing the exposed structures of the zone, for swinging the sledge and dragging scrap. The others appeared molded for boxing alone, for punching into and through a man. Every opponent all veins and teeth, hungry eyes bursting from tight skin, angry under the brow of a padded helmet. They had taken the given and built the desired. He had made what body was necessary for his work and now he sought to bring it to a new task.

He didn’t want a trainer, couldn’t pay, wouldn’t ask. He trained by fighting. By getting hurt. Education by knockdown. Gloved fists pummeled his stomach but the next time a boxer came for Kelly he’d find the same tactics denied. Experience had made him who he was. If he could get hurt he could get better. A man raised his tattooed forearms over his face and Kelly battered his defenses until the man cried out. Kelly liked the way winning was temporary. You earned it but it didn’t last. He liked how after he showed his opponent he would give no quarter, then the man spit and swore and came at him senseless, his entire body open to the blow.

When Kelly got his insurance he went to the doctor but he didn’t tell the girl with the limp he went. The doctor measured his blood pressure, listened to the thumping chambers of his heart, counseled him to avoid strenuous activity. He laughed and told the doctor what he did for a living. The doctor lifted his chin, probed around his neck and jaw, put a light to his eyes and ears and nose and throat. His fingers and hands were blacked from work and his body was bruised as rotten meat and the doctor suggested nothing he didn’t believe he could be paid for. Kelly had insurance but the doctor said mostly it would only promise that if he died he would die in a bed.

Now Kelly walked the zone like a squared spiral, moving outward from his starting point in a series of right turns, every rotation allowing another block’s length to stretch the circle. He bought graph paper, plotted each block of buildings, their various modes of inhabitation. He got to know every boarded house, every chain-link fence. He found members of the city watch in the zone and he signaled to them, offered to buy them coffee. Each questioning began with the necessary small talk, family, children, church, work. The endless sameness of the weather. Eventually they invoked the holiness of their task: if the police wouldn’t protect their communities they would protect the city themselves.

Whenever Kelly encountered the volunteer built like a linebacker again, the linebacker pulled Kelly into a headlock or else faked a jab to his stomach. Then to resist punching back. To resist locking his arms around the slab of the man’s belly and lifting, trying to put him on the ground. Later the linebacker answered Kelly’s questions over coffee, handling his crude maps, adding landmarks Kelly would never have known. The locations of legendary shootings, rapes, hate crimes. The names of families long extinct or fled.

What exactly are you doing here, the linebacker asked, and Kelly shrugged.

I’m looking for someone, he said. Somewhere in the zone, he said, then waved his hands across the graph-paper maps spread out across the diner table. Somewhere out here.

It’s a big city to hunt a person in, the linebacker said. You’ll need something better than luck if you want to see it through.

The linebacker carried a pistol, a black shape inside a black holster tucked under his jacket. He taught gun-safety classes, he said, helped others get concealed-carry permits. He sold guns out of his house but only to men he trusted.

Whatever you need, the linebacker said, I can help.

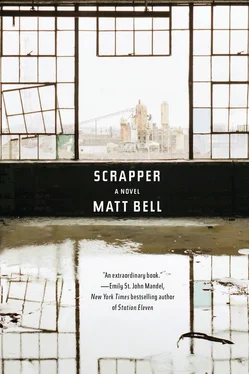

The year dwindled. The farther Kelly moved from the center of the good story the more dangerous the story seemed. Somewhere in the zone there would be a space where no one suffered names. He wouldn’t ascribe complexity to every actor. The more blank the image the more able to inspire terror, to excuse hurt. He moved through the frigid desperation, a lone striver walking rooms where many had lived, studying floor plans that had housed the generations, three children to a bed, two beds to a bedroom, houses standing through booms unimaginable, eras resigned to the unknown expanses of the past. When he arrived home he added the squares of graph paper to the case notes, tucked them loosely in the back of the notebook. On nights the girl with the limp worked latest he thumbtacked the maps to the walls of his living room, placing each block beside its neighbors, each sheet covered with simple diagrams, streets drawn in a shaky hand, outlined squares and rectangles for houses, filled in black if they were confirmed vacant. He paced the room, poured a drink, considered the spreading stain. In the zone Kelly had seen the lengthy shapes of the world, how what was to come was set down by what had passed, the long story of progress bendable only by degrees. He’d acquire the tools, he’d choose the space, he’d find the man in the red slicker, he’d take him and make him pay.

Because what if a degree was enough. What if the slimmest fraction of a degree made all the difference.

How to press an advantage. How to break through a defense. How to feint and have the feint believed. How to make a man of eighteen or twenty-one or twenty-five worry the peak of his powers wouldn’t be enough. How to accept the same when it was your turn to fall. To stay in the ring three minutes at a time, to take the fists upon your head and body until each punch stuck in the meat of your bones. How to stay. How to stay. How to bear anything no matter the hurt. How in another age agony had meant contest . How there was nothing in the fight not brought there by an act of will. How to take the other’s will and push it out of the square. How to have all your options reduced to violence, no way out except to strike or be struck.

Читать дальше