The suspect, he thought. The volunteers were right: he had been thinking about the suspect. Maybe there was something more he wanted done. Or else something he wanted to do.

He wasn’t scrapping anymore but nights the girl with the limp worked he drove the oldest neighborhoods, cruised the streets bordering overgrown fields and crumbling industrial parks. He bought a police scanner, affixed it to the dash, listened for arsons and burglaries, domestic violence, the reported sounds of gunfire. Dispatch spoke at a remove, spared the details. Most nights he heard her voice on the airwaves, disappearing fast into a squelch of turning static. Her radio voice was pleasantly dispassionate, speaking from within an unfolding tragedy but without inflection. She narrated codes, directions, the street addresses, and the names of cross streets. Sometimes he went the places she named. If he didn’t know how to get there he plugged the address into the dash and then there were two female voices telling him where to go. The satellites pointed him in the direction of her mind. He often beat the first responders to the scene but what could he do next, what else except drive by a burning building and hope everyone inside had escaped the flames.

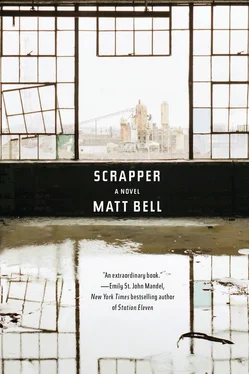

He wasn’t scrapping but it didn’t keep him out of the oldest buildings. The night he found the boy he had come home to his apartment and found all his relics uncharged, their thrum dissipated. His life had changed but he didn’t want to lose what he’d gathered, needed more. He pry-barred the lock on a door in a house he was sure was empty and walked its rooms, ran his fingers through the carpet, put his palms against the plaster walls. There was a mailbox out front with a series of numbers meant to separate this home from all others. Someone could live here again but who. Someone had owned this house but where had they gone. He listened to the boards creak, waited to hear the way the house held both a whisper and a hush. The absence of expectation: nothing more would happen in this house. The phone would not ring, the kitchen timer would not go off, no one would knock on the door. He’d gotten used to so much quiet but never this.

The boy still appeared on the television but less and less. What had happened to the boy was a crime but who would solve it. The scene had given the heavy detective nothing, thanks to Kelly’s obscuring work, his covering of every surface in drywall dust and tracked dirt. He gauged his responsibility, tried to assign fault in right proportion. He tried to imagine what might happen next, if the kidnapper knew his name, the name of the boy. He tried to imagine if the balance of power might be upset, if he could come to know the watcher, the man in the red slicker.

From the relics he’d found in the zone Kelly had learned it wasn’t possible to know what the hearts of others would treasure or protect. He was coming to believe that if he wanted something saved he had to save it himself.

THEY ATE COLD SANDWICHES and hot soup in a diner, split a piece of apple pie for dessert. She told him about her week, rehashed all the stories that made the newspaper. Even worse, she said, were the ones that never would, the lower cries of human misery answered at her terminal every hour of her working day: a mother with her kitchen on fire, a wife with a voice slurred by drink or bruises, a child calling for help from the last pay phone on earth, lost and unable to explain where she was, where she was supposed to be. The car crashes, the slip and falls, the temporary troubles and the irreversible blows. The insane cruelty of chance, the magnificent dangers of the everyday, all filtered through her station.

When I started this job, she said, I thought the voices went right through me. I took each call, passed its information to someone who could help, moved on.

The first month, she said, I couldn’t remember the calls by the time I got home. I dealt with them and then I forgot. But I didn’t stay uninvolved forever. I became something else.

A salvor, Kelly said. Salvor. A word he’d been thinking of ever since the first step out of the basement in the blue house. One possible future.

She said, One day I came home and I told someone else what I’d heard on the phone. I’d never done this before, never talked about the day. The someone else was a man but who he was isn’t important. The story I told him was about a boy who had fallen into a sewer opening while playing with some friends. They shouldn’t have been doing what they were but their mistake wasn’t my concern. My concern was getting the boy out of the hole.

There’s always a boy to be rescued, he said. Or else a girl.

Public works, she said. The fire department. Both called and put on the case and when I hung up the phone I didn’t know how the case would end but I believed it would be resolved. It was so simple, a boy at the bottom of a ladder, too scared to climb back up, maybe hurt.

She stopped talking, stuck her fork through the pie to scrape the plate below, carving the slice into smaller pieces without taking a bite.

The fire department radioed back, she said. This happens. They need more information than what I’ve provided, or else the person calling has made a mistake. It’s so hard to be accurate in the presence of trauma. The firemen and the men from public works had arrived at the open sewer cover to find the first two boys, the one who stayed and the one who made the call. From the street the men couldn’t see the third boy at the bottom of the hole and when they went down into the sewer — it was ten feet down, nothing any man and a flashlight couldn’t handle — the boy wasn’t there. There was nowhere for a boy to go but the firemen searched the shallow passage, trolled the water, shined their lights across every foot of the sewer entrance, all its holes and cubbies, any place a boy might have hidden.

Why would he hide? she asked. From who? Public works unlocked the gratings at each end of the chamber and a further search was organized. Even as they searched they must have known they wouldn’t find the boy, because how would he have gotten past those same grates? At first they thought the boys had made up the fallen friend, but he was real enough. It turned out the friend’s parents hadn’t seen him since before school. They never saw him again.

She said, Once there was this single mystery, the missing boy in the sewer. Now there are so many. Your boy too. Because you saved him — at last she lifted a bite of cold pie to her mouth — but from who?

It’s not the unsolvable that bothers me, she said. It’s the solvable unsolved.

She wasn’t as emotive as every other woman he’d dated. He didn’t know the shapes of all her thoughts, had no taxonomy for her modes of expression and speech and careful withholding. After her third bite of pie he realized he didn’t have to respond. As with every other conversation it was often enough for him to be the listener, to remember what he’d been told.

There was a grocery in his new neighborhood but he didn’t need more food. He bought a handle of whiskey, a twelve-pack of beer, a carton of cigarettes, a squat spiral notebook, and a package of black pens. Back in his apartment he started at the beginning, listed details, whatever precursors of memory he might be able to tug. What had he seen. What did it mean. Who had hurt the boy. The boy had given the detective only the mask, the gloves, a red slicker; no identifying details, no sure guesses of height or weight. As if he’d been abducted by a ghost or an idea. Kelly could picture someone more solid but the imagined man wore a face born from movies, crime procedurals.

In the notebook he wrote what he had not told the heavy detective: How before he’d returned to the basement, he had tried to pretend he’d never seen the boy. And how when he returned it was for a moment the blankness he’d seen.

Читать дальше