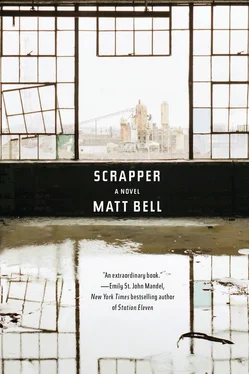

It wasn’t the cost of the object history wanted preserved, only the object. And this was the week a scrapper died inside a closed hospital, cutting steel beams, buried beneath a collapsing roof. This was the week a scrapper was shot by a private security guard inside a tenantless apartment building. This was the week a scrapper dropped an acetylene torch from atop a ladder, cutting the hose between the tank and the torch, igniting the insulation falling out of the ceiling. This was the week a scrapper climbed a power pole to cut through the dead wire and found the wire fully charged. When the fire trucks arrived the men had to wait, hoses in hand, until the utility company could turn off the power. By then the scrapper was fused to the pole and the firemen had to cut down the top half to take him away.

This life Kelly was living. How long did he expect it to last.

What are you thinking, the girl asked.

He looked up, shook his head, thought her name, said it aloud: Jackie. Sometimes it was so easy to say it.

Later they lay beside each other in her bed, hands touching, legs intertwined, and into the silent dark she said she didn’t like to talk about her past either but she couldn’t put off the future forever. She asked if he knew what he was getting into. Her limp wouldn’t be the last thing. Already there were attacks where she struggled to breathe, where her vision blurred and she lost sensation in her fingers and toes. Involuntary systems got confused, voluntary ones unresponsive. Once she’d shit herself at work. She was older than he was and she wasn’t going to live forever.

He shushed her, said it didn’t matter. He said, Okay. He said, Tell me everything. Tell me what will happen and I’ll tell you if I can handle it.

She said physical activity could make it worse. She had to be careful not to overheat herself or else it would cause an attack. No matter what she did there would be attacks and there would be relapses and after every attack she would be worse than she was before. There was no going back. The disease was progressive, untreatable, incurable. The doctors believed they knew how to slow it down but a delay was the best they could hope for.

Some patients smoked pot. Some self-infected themselves with hookworm to train their immune systems to fight. It was all guesswork. She took her pills and lived her life.

He nodded, slid closer, made a move.

No, she said. First tell me how much of this you want.

We’re together, he said. And not because of this. If we come to an end this won’t be why.

THE MORNING OF THE FIRST snow, Kelly drove an unexplored length of the zone, coasting the truck slowly from driveway to driveway, assessing doors left open, windows missing, porches collapsed by the removal of their metal supports. Some of the houses had been scrapped already but he knew he would find one more recently closed, with boards in the windows and an intact door. A space empty but not yet shredded. The zone sprawled beneath the falling snow, cast its imperfection wider than he could accept, but eventually he chose a house — two floors, blue paint on the siding, gray boards over the windows, a yellow door, surrounded on both sides by vacant lots, with only a burnt shell standing watch across the street — then went to the door and knocked, yelled greetings loaded with question marks.

He waited, yelled again.

He raised his hood, returned to the truck for a pry bar. He moved out of the front yard and along the side of the house, the brown grass crunching beneath the snow. Beside the blue house was a metal gate in a chain-link fence but the gate wasn’t latched. At the first window he pulled back the covering board, found the glass gone. He peeked in, searched for furniture, a television or a radio. Instead stained carpet, signs of water damage, a kitchen with no dirty dishes but an intact gas range, a sink and faucet he could wrench from the countertops.

He lifted himself through the window. Leading away from the kitchen was a staircase to the second floor and also a basement door, closed and latched with a padlock. He’d cut the lock later, after the other work was done. Upstairs the bedrooms were small, sloped to fit beneath the peaked roof, but there was enough room to swing a sledge. Back downstairs he opened the front door — the door not even locked, but he hadn’t thought to check before climbing in the window — then crossed the snowy yard to the truck for the rest of his tools. Already his first footprints were buried beneath the accumulation and afterward he wouldn’t be able to convince himself there had been others, no matter how insistently he was asked.

In the master bedroom he flicked the light switch to check the power, then aimed above the outlets and swung. He took what other scrappers might have left behind. With a screwdriver he removed each metal junction box from the bedroom, then in the bathroom he cut free the old copper plumbing from under the sink and inside the walls. He smoked and watched the snowfall through a bedroom window, the world hushed wet under its weight. In the South he’d forgotten the feeling of a house in winter, the unexpected nostalgia of watching the world disappear under snowfall. He put his forehead to the cool glass, watched the stillness fill the pane.

Downstairs he dismantled the kitchen, disconnected the stove from the wall, cut the steel sink from the counter. He worked quietly in what he thought was the wintry hush of the house but later he would be told about the amateur soundproofing in the basement, about the mattresses nailed to the walls, about the eggshell foam pressed between the basement rafters.

The soundproofing meant the boy screaming in the basement wasn’t screaming for Kelly but for anyone. There would be talk of providence but what was providence but a fancy word for luck? If the upstairs of the blue house had been plumbed with PVC Kelly might not have gone down into the basement. But then copper in the bathroom, but then the copper price.

It wasn’t until he cut the padlock’s loop and opened the basement door that he heard the boy’s voice, the boy’s hoarse cry for help rising out of the dark.

As soon as Kelly heard the boy’s voice the moment split, and in the aftermath of that cry Kelly thought he lived both possibilities in simultaneous sequence: there was an empty basement or else there was a basement with a boy in a bed and it seemed to Kelly he had gone into both rooms. Kelly thought if he had fled and left the boy there and disappeared into the night he might never have had to think about it again, couldn’t be held responsible for everything that followed. Instead he had acted and now there would be no knowing where this action would stop.

Kelly climbed downward, descending the shaft of light falling through the basement door. His clothes clung to the nervous damp of his skin as he stepped off the stairs toward the bed at the back of the low room, toward the boy restrained there, all skin and skinny bones, naked beneath a pile of blankets and howling in the black basement air.

One by one each element of the scene came into focus, the room’s angles resolving out of the darkness, each shape alien in the moment, the experience too unexpected for sense: the humidity under the earth, the musky heat of trapped breath and sweat, piss in a bucket; the smell of burrow or warren, then the filth of the mattress as Kelly slid to his knees beside the bed, his headlamp unable to light the whole scene; the boy atop the stained and stinking sheets, confusing in his nudity, half hidden by the pile of covers, a nest of slick sleeping bags and rougher fabrics partially kicked off the bed, and beside the pile of blankets a folding metal chair.

The boy’s screaming stopped as soon as Kelly lit his features but Kelly knew the boy couldn’t see him through the glare. He shut off the headlamp, removed the glow between them, let their eyes readjust to the dimmer light. He leaned closer, close enough to hear the boy’s rasping breath, to smell his captivity, to touch the boy’s hand. To try to bring the boy out of abstraction into the sensible world.

Читать дальше