“’Allo, Ms. Harriet!” he says, pocketing his cell phone. “Have you lost your way?”

“Gracious, no.”

“May I deliver you?”

“No, thank you, dear,” Harriet says. “I’ll handle my own deliverance, thank you very much.”

December 22, 1959 (HARRIET AT TWENTY-THREE)

While there’s only so much you can do to fudge the math, nobody makes an issue of bouncing baby Skipper’s arrival, seven and a half months after your wedding day. And just in time for Christmas! You’ve got what you wanted, Harriet: stockings festooning your hearth. And you got a lot more in the bargain, too: a colicky infant who doesn’t sleep and never stops filling diapers, a ruined figure, a husband who’s never home. You’ve got endless nights in steamy bathrooms and endless days of domestic toil. Somehow, though it seems impossible, you didn’t see this coming. Suddenly your life is filled with talcum and baby oil and laundry soap. Pee and poop and spit-up. Tide, Wisk, Cheer, you’ve tried them all — yes, even All! You’ve tried reading magazines while Skip is napping, even television. But nothing seems to whisk away the tide of despair. Nothing seems to cheer you. All of it is futile.

Filing deposition notices suddenly doesn’t look so bad next to the tedium of homemaking. Drafting court appeals was never this thankless. And this is nothing compared to what you’ll endure with Caroline. When you get a moment’s leisure, you’re cagey. Just look at you, Harriet, pacing the house, displacing pillows, rearranging furniture. Looking for purpose. When all else fails, you go shopping.

Yearning to be noticed, you experiment with hairstyles, cinch your waist with fitted jumpers, and when that doesn’t work, you starve yourself. Look at you, with your plate of turnips. And, by God, it works! Your figure returns! But nobody seems to notice, not the butcher, not even Bernard.

But like everything else, it’s only going to get worse, Harriet. Within three months, Bernard will be around even less, landing a job as plant manager at Blum Bearing, where he often works two shifts. When he comes home exhausted, he takes a mild interest in the child for about ten minutes, eats the warmed-over dinner you’ve set before him, and then hides behind his newspaper for the rest of the evening.

In bed, he turns his back to you, and you wonder what you’ve done.

You understand the pressure he’s under, the weight of responsibility he must feel. And yet you’re powerless to share this responsibility. The best you can do is pick a good melon and keep the linoleum clean, launder his work clothes, and stock the refrigerator. Depleting as they are, these accomplishments feel empty.

Oh, but let’s not forget the joys of domesticity, Harriet! Here you are, decked out in curlers and a terry-cloth bathrobe with baby Skipper in the ER shortly after he swallowed the paper clip. You berate yourself for being a useless mother, who can’t even keep her child out of the hospital. All you can do is scour his poopy diapers for the next three days, looking for the offending object.

And here you are again, in the same bathrobe and curlers, consulting with firefighters who have responded to your frantic call regarding the smoking Maytag. Five armored giants rush into your laundry room with axes only to return minutes later, slightly deflated. Turns out, the machine is simply overworked.

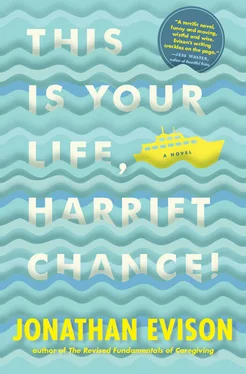

This is your life, Harriet, what it’s become.

But do not lose heart. Things will get better after the first year: Skip will hit his sleeping stride, start taking the bottle, the colic will subside, you’ll find a reliable babysitter in Cindy Blum. Bernard will take a full week off next Christmas. But by then, Fourth and Union, and the joys of your former life, will already seem a long ways away. That other Harriet, the self-realized one, has gone on without you.

August 13, 2015 (HARRIET AT SEVENTY-EIGHT)

When Harriet arrives home from Sunny Acres, she’s thrilled to discover Skip’s silver SUV in the driveway in spite of the fact that it’s parked perilously close to her dahlias. She thinks guiltily of the creased fender, for which Skip — like his father, a zealous maintainer — will surely expect an accounting.

Halfway up the drive, Harriet’s stomach tightens as she spots Caroline peering out the kitchen window. Smiling stiffly, Harriet issues a little wave. Suddenly, her thoughts are racing. What will she make for lunch? Does she have time to bake something? She hopes the living room isn’t a mess. Sandwiches, she can make sandwiches. They can eat outside on the patio! Maybe they’ll stay the night. Oh, what a surprise!

She finds Skip in the living room in front of the TV, eating dill pickles straight from the jar. Snapping off the television, he swings his feet off the coffee table and sets the remote aside.

“Hello, dear, what a surprise!” she says.

He walks to the kitchen and bends down to hug her. At fifty-five, with flecks of gray marking his wavy hair above the ears, he still manages to look boyish in his purple UW hat and running shoes.

“Hello, dear,” she says to Caroline, who makes no move to hug her.

At forty-eight, with sallow cheeks and scarecrow hair, Caroline looks like Skip’s elder by at least five years.

“What are you two doing here? I had no idea!”

We thought we’d pop by for a visit,” says Skip. “We both had the day off, so we figured, you know, let’s drop in on Mom.”

“How wonderful! Oh, but I do wish you would have called ahead, dear, so I could prepare something. Let me make you a sandwich.”

“Nah, it’s all right, Ma, I just had a few pickles. I’m good.” “Caroline, honey, let me make you a sandwich. You look so thin.”

“Gee, thanks, Mom. You always know how to make me feel good about myself.”

“Honey, I didn’t mean it like that. C’mon, I’ll set up the patio. I do hope you’re staying the night? We can rent a DVD!”

“Look, Mom,” says Skip. “The thing is, we didn’t just pop by for a visit.”

“Oh,” says Harriet, crestfallen. “You mean, you’re not staying?”

“We can’t, Mom.”

“Surely you can at least stay for dinner?”

“Mom,” says Skip. “I got a call last night from Father Mulligan.”

“ Mullinix , dear. Where on earth did he get your number?”

“He told Skip about the phantom WD-40,” says Caroline, lowering herself into Bernard’s recliner.

Skip sits down on the sofa, and immediately leans forward. “He said you were acting really strange, Mom. He was worried.”

Harriet feels herself blush, at once from embarrassment and irritation. “I was exhausted,” she says. “I served downtown all day at the prayer station. There’s no air-conditioning down there. Did Father Mullinix tell you that? I was overheated. But I’m perfectly fine now, I assure you.”

It comforts her to know that Skip genuinely worries about her.

“Mom,” he says. “We’re just concerned. He said you thought you had dinner with dad at the Bon Marche.”

“Frederick and Nelson.”

“Right. Frederick and Nelson.” Skip doffs his cap, runs a hand through his thick hair. “Mom, Frederick and Nelson closed twenty years ago! I don’t even think that old buffet did dinners.”

“I saw him, Skip, with my own eyes. I touched him.”

“Mom, I had a dream my hands were made of soap. But look, they’re not!” He submits his outthrust hands as evidence.

“It’s not the same thing.”

“It is, Mom. It was a dream.”

“No. It wasn’t.”

“Okay, what then? A hallucination?”

“Not exactly,” says Harriet.

Читать дальше