But something happens to Caroline in the close quarters of the elevator: all the defiance seems to drain out of her, right before Harriet’s eyes. Every muscle of her body seems to slacken at once.

“Thanks for getting me out of there,” she says.

Harriet reaches out and clutches her daughter’s hand, but Caroline pulls away as the elevator eases to a stop.

In the blustery air of the observation deck, Caroline, her kinky hair blowing sideways, crosses her arms over her chest.

“Dear, maybe we should go fetch your coat,” says Harriet.

“No.”

“But darling, you’ll freeze.”

“I want to freeze.”

The deck is deserted, as they drift wordlessly toward the stern, with the wind at their backs.

“Well, I don’t know how you can stand it,” says Harriet.

At midship, a steady blast from the heating vents envelops them suddenly in the illusion of a tropical night.

“Now that’s more like it,” says Harriet, lowering herself onto a wide bench. “Sit down, dear.”

But Caroline moves to the rail, where she stares into the darkness. Harriet wonders whether she should go to the rail or stay put and give Caroline her space. Watching her daughter’s back, the slow rhythmic convulsing of her shoulders, her dark mess of hair blowing crazily, Harriet contemplates the distance between them and wishes with an ache that the gap was only the mere ten or twelve feet now separating them. If only she could will her daughter back through the years.

Harriet is about to go to her when Caroline turns. “Five years thirty-one days,” she says, plopping down next to Harriet. “Fuck. Fuck. Fuck.”

“It’s my fault, dear.”

“I’ve been looking for an excuse. You and Skip just made it convenient for me.”

“Oh, Caroline. I’m so sorry. I’m a wicked person.”

“What are we even talking about, here, Mom? Who am I? Who should I be begrudging?”

Harriet balls her fists in her lap. She doesn’t know where to begin. She supposes, with the vague personal dissatisfaction and the ancient self-loathing, for which Charlie Fitzsimmons was only an antidote, or perhaps a symptom of or, at most, only part of the cause. But where did that begin? And what was it? And how, at nearly eighty years old, could she not know this about herself?

“You know what?” says Caroline. “Maybe I don’t wanna know. To tell you the truth, that might be too much right now.”

She bows her head, her ragged breath giving way to a sob. “Goddamnit, I fucked up again. Why do I always fuck up? I swear to God, it’s like I wanna fail. Skip’s right.”

“Forget Skip,” says Harriet. “Don’t talk like that. Part of it is genetic, you know. At least you’ve had the courage to face it. My God, Caroline, what did I ever do? And that may be the least of my problems. Lately, I’m discovering all kinds of deficits in myself. I don’t even know who I am anymore, Caroline.”

“Pfff. You’re telling me. I never have, Mom, not my whole life.”

“You’d think the growing pains would end at some point, or at least slow down,” says Harriet. “But oh no.”

“If anything, they accelerate,” Caroline says.

Harriet scoots closer and tentatively takes her daughter’s hand. This time, she accepts it.

“I’m sorry, dear. I’ve been a terrible mother. You did nothing to deserve me.”

“Who is he?” she asks.

“His name is — was — Charlie Fitzsimmons.”

“He’s dead?”

“He must be.”

“You loved him?”

“Never.”

“Does he know about me?”

“No.”

“Did Dad know?”

“No.”

“So, I was. . what, then? A mistake?”

“Don’t ever say that.”

“Well? Then what?”

And so, Harriet breathes deeply of the warm air, bows her head, falters once, falters twice, gives pause, and finally begins her explanation. It begins in the waning minutes of 1936, with a little girl, confetti in her hair, hanging upside down in a bassinet.

August 17, 1946 (HARRIET AT NINE)

Ding-dong-ding, thwack-thwack-thwack, how on earth did we arrive way back here, Harriet? It’s 1946, and Vaughn Monroe is on the radio. If you listen closely, you can still hear them celebrating victory in Times Square.

Welcome to postwar America, where spirits are high. It’s been another prosperous year in the Nathan household, and nobody throws a company barbecue like the boys at Nathan, Montgomery, Ferris, and Fitzsimmons. We’re talking Indian smoked salmon. Waldorf salad. Frankfurters the size of Chiquita bananas. All the Coca-Cola a nine-year-old girl can drink.

And lucky you, Harriet, of all the youngsters, you get a ride on Charlie Fitzsimmons’ speedboat, and boy, she’s a beaut. Good old Charlie Fitzsimmons. The whiz kid is now a wizened veteran of the law. One of the best in the city. A silver-tongued fox, a real asset to the firm. Your father venerates the man, talks about him like the son he never had, though Charlie’s only ten years younger.

But you don’t like Charlie, do you, Harriet? Or maybe that’s not entirely accurate. You are acutely ambiguous about Charlie.

On the drive home, in the backseat of your father’s Hudson Commodore, top down, you finally muster the courage to say so.

“What do you mean you don’t like the way he talks to you?” says your father, slightly tipsy — slightly, that is, by Nathan, Montgomery, Ferris, and Fitzsimmons standards.

“Like I’m already grown up,” you say.

“Well, that’s because you’re a smart little girl,” he says, his eyes smiling in the rear view mirror. “He respects you.”

“Goodness,” says your mother. “I hope you weren’t rude. If you said anything impolite, young lady, we’re driving right back to Charlie’s this instant, and you’re going to apologize.”

“No,” you say. “I promise I wasn’t rude.”

The thought of seeing Uncle Charlie (as he insists you call him) again, his coarse hands, his hairy knuckles, his gap-toothed smile, fills you with dread and anxiety. And the worst part is, you’re ashamed for feeling thus, because Charlie thinks you’re smart. Charlie respects you. Apparently, he’s among the first. Charlie doesn’t think you’re fat. He forever goes out of his way to tell you how special you are.

“Well, then,” says your mother, as though she can hear your thoughts. “Maybe you ought to work on being a little more grateful.”

“Yes, ma’am,” you say.

Obviously, there’s no use telling your parents why else you don’t like Charlie Fitzsimmons, and his thin lips pressed against your forehead, and his hairy fingers groping beneath your bathing suit to pet you there. No use in telling them about the gentle way he spoke to you as he fondled you where your breasts had yet to begin their miraculous budding, nor the adoring things he said with his face buried in your lap. They wouldn’t believe you anyway. There’s no use telling anybody. Even Ginger, your golden retriever, doesn’t seem to want to hear it. That will be your little secret for the next seventy years, Harriet. Just you and Uncle Charlie.

Charlie will continue to treat you with respect. He’ll always make a point of telling you how smart and capable you are. How he could see right from the beginning how special you were, how he knew he could always trust you. Like your parents, he will regale you with the story of the upside-down baby girl. He’ll tell you these things your whole life, right up to that after-hours dalliance on your office desk, twenty years hence, by which time, his speedboat will be a distant memory, buried deeply.

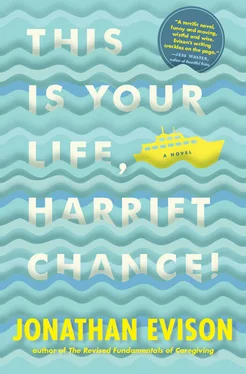

This is your life, Harriet, the one you didn’t choose.

August 17, 1946 (HARRIET AT NINE)

Читать дальше