“No kiddin’? Went to school with a fella named Boyd Chance. You got people in Bath County?”

“Not to my knowledge, dear.”

“Where y’all from?”

“Washington State, dear.”

“How about that? Owingsville, Kentucky, here. This is us,” he announces as the elevator door opens on a long stretch of ghastly carpet.

Dragging the luggage, Kurt guides her down a cramped hallway toward the rear of the vessel. He’s sweating again after thirty feet.

“Whoooeee,” he says, catching his breath. “They don’t make it no cake walk now, do they?”

“No, they certainly don’t.”

At last, Kurt deposits her in front of her cabin door, where he instructs her on the use of her card key, his great midsection still heaving.

“Bless you, Mr. Pickens.”

“Y’all have a good cruise now,” he says, resuming his ungainly stride. “See you at the buffet.”

The cabin, furnished roughly as it had been in the brochure, is half the size it appeared in the photos. The decor is bland and inoffensive: beiges and muted pastels, rattan and smoked glass. The art, nautically themed, is inconspicuous. The overall effect is an airport Radisson in miniature.

Harriet immediately unzips her wheelie bag and checks on Bernard’s ashes. Finding the container intact, she sets it atop the dresser, then lowers herself into the love seat, hoping against hope that she’ll be able to lift herself out again.

If things keep up at this pace, she’ll drop dead before Skagway, a thought that — at the moment — is less disconcerting than it should be. Closing her eyes, she takes several deep breaths and stares at the back of her eyelids.

Dear Lord, forgive me for questioning your wisdom. I’ve leaned on my own understanding, and I’ve had moments of doubt. But I have not lost faith, Lord.

She feels better immediately. It’s all out of her hands now. Before long, her body is one with the quilted cushion of the love seat as the heavy veil of sleep descends.

Then sunlight floods the room.

Harriet turns sleepily to meet a gentle breeze, and there, standing on the veranda not ten feet from her, clad in a crisp gray coverall, hair Brylcreemed to a shine, stands Bernard, looking just as he did when she first met him in 1957.

“Lot of hand sanitizer,” he observes. “That’s good. You get a GI breakout on this tub, and bingo bango, there goes your cruise. They’ve got dispensers at the end of every hall-way — every twenty feet on the Lido deck. Not the most decorative things, soap dispensers, but smart.”

“Oh, Bernard, you’re coming.”

“You tell me,” he says, crossing the threshold, whereupon he begins subjecting the room to a casual inspection — squeezing throw pillows, opening cabinets, running his fingers over the desktop, then checking them for dust.

“Kind of small,” he concludes. “But efficient. How’s the water pressure?”

“I haven’t tested it.”

“Meals included?”

“Yes, buffet and dining room.”

Jutting his lower lip out, he nods, mildly impressed, as he raps a wall with his knuckles to determine its thickness, then pauses to inspect the framed print above the love seat, tilting his head curiously one way, then back the other.

He’s so close, Harriet can smell him, his Brylcreem, his starch, and yes, even his hand sanitizer.

“I feel so strange,” says Harriet. “Am I. . dead?”

“Not yet,” he says, examining the television remote. “Trust me, you’ll know.”

“Should I be frightened?”

“Won’t do you any good,” he says, setting the remote aside. “Don’t bother planning.”

“That doesn’t sound like you. You made our burial arrangements the day we moved to the peninsula.”

“Twelve ninety-nine was a steal. Copper deluxe caskets, hardwood — the good stuff.”

Here he drifts absently toward the bedroom portion of the cabin, pausing at the dresser to pick up the yogurt container, considering its weight before reading the label.

“Good plot, right? Conveniently located. Shady, not too crowded. Nice place to be buried.”

“It’s beautiful, I’m sorry. I know you would have preferred it that way. I was just. . it was selfish of me.”

He waves it off. “Look, I understand. Who needs all the ceremony at a time like that. And what’s the difference? I take up less space this way. And think of the money you’ll save on flowers.”

Gently, he sets down the ashes. “Glacier Bay, huh? Not what I had in mind for a final resting place exactly.”

“You don’t approve?”

“Actually, I’m starting to like the idea. Look, there’s something I’ve gotta tell you. You deserve to know. Things we can’t plan for — they happen, Harriet.”

“You think I don’t know that?”

“I’m not talking about Alzheimer’s. I’m talking about. . situations. Not ideal ones. We cause them to happen even when we don’t mean to. We’re weak, Harriet, and I was weaker than most. The best we can hope for is forgiveness. I hope you can accept that.”

“It sounds like an apology.”

“It is.” He turns to face her directly. “But it probably won’t do me any good.”

Slowly, still facing her, he backs between the parted drapes and onto the veranda. “I really am sorry,” he says, receding.

“You shouldn’t be,” she says, a sleepy smile clinging to her face.

April 16, 1973 (HARRIET AT THIRTY-SIX)

It’s true, Harriet, there are a few cracks beginning to show in the foundation of your marriage by the time you reach your ivory anniversary. But that’s a normal part of the continuum. Having apparently said all that needed to be said over the years, you and Bernard don’t talk much anymore. You haven’t had sexual relations in months. How long since you played a game of Scrabble or went to a movie? Again, nothing catastrophic, nothing that’s going to bring down the house, just the ruinous effects of time and familiarity.

Love grows quieter, Harriet, it’s true. People evolve, or they don’t. Either way, they grow apart. Sometimes they get busy. It’s not as if ball bearings are threatening to kill your family life, but last week Bernard missed Caroline’s birthday and Skip’s home opener. Tonight he will miss the occasion of your anniversary. But to his credit, he will remember the day and phone you from his hotel room, summoning the appropriate enthusiasm. And you’ll be glad to hear his voice.

Yes, all in all, things could be a lot worse. You could be divorced. You could be a widow. Gallo could stop selling wine by the jug. And where would that leave you, Harriet? Bored and sober.

The fact is, you’ve adjusted your expectations. You’re no longer a romantic. After fourteen years of marriage and two children, the glass slipper no longer fits. But being Mrs. Bernard Chance isn’t so bad. If not happy, you’re comfortable. You have two bright, healthy children and a nice house in a desirable neighborhood. Your refrigerator is always full, and every year so are those Christmas stockings. And though you’re relations have tapered off, and boredom has set in, seventeen years after he showed up at Fourth and Union clutching a bouquet, Bernard, still handsome, though frequently absent, perpetually grumpy, and often elusive, is still your husband, still the man you aim to spend the rest of your days with.

And you wouldn’t have it any other way.

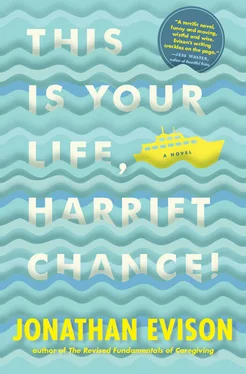

This is your life, Harriet, for better or worse, in sickness and in health, until death do you part.

August 19, 2015 (HARRIET AT SEVENTY-EIGHT)

The dreamy smile still clings to Harriet’s face, as she pushes herself out of the love seat and begins unpacking her suitcase. Refolding her clothing (good heavens, those animals at customs have made a mess of it), she nestles each garment neatly into its tiny drawer, now and again smiling her satisfaction at Bernard’s ashes, atop the dresser. It’s as if he’s still in the room. She swears she can still smell his Brylcreem.

Читать дальше