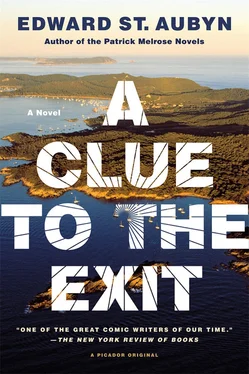

The wind started to subside as I walked downhill. The calanque itself was almost still. I found a hollow in the rock and watched the frantic sea calmed and confused as it was funnelled towards the beach, sometimes crashing in, sometimes bobbing up indecisively. The moon was not yet shining into the creek, but I saw it whitening the waves further out to sea. Lines of seaweed were stranded on the sand, some dry, some lolling in the surf.

I seemed to have completely lost the conviction, which had come to me so triumphantly when I first arrived on the island, that beauty was the natural order of things. The first time I saw this coast I was blown away by its visual brilliance. Was I misled this evening by the lure of symbolic thinking? The sun and moon mingling blood — wasn’t it enough that the moon was briefly reddened by the setting sun? And yet the idea that they were mingling blood had been the content of my thoughts at the time. The sexual, the tragic and the symbolic registers were as much part of my consciousness as the optical. Beauty could not depend on an allegedly direct encounter with the thing that seemed beautiful. No such directness was possible. The sun and the moon, even if I landed on them, would come to me in the form of knowledge. There could only be more or less intimacy with the mental reality in which they made their appearance. There might be a primordial encounter with that knowledge but not with the object itself. I was not being solipsistic. I didn’t want to deny that the sun and the moon were out there, with a lifespan of their own, somewhat longer than mine, and that some kinds of knowledge referred to the facts of the case whereas others did not. But whether it was Phoebus, skin cancer, a small yellow star, the bleeding sun or entropy that appeared in consciousness, real beauty could only come from this intimacy with mental reality, whatever it might contain, and not from the inherent beauty of the thing or the thought. Who has not noticed a mood swing turn the petal-coaxing sun into the maggot-breeding sun? Sometimes I am delighted by things being as they are, sometimes by their resemblance to something else. Sometimes understanding how things work weakens my desire for metaphor, sometimes the desire is sharpened by understanding how things work.

The moonlight had reached the creek by now and made it look like boiling mercury. Sandflies, celebrating a warm human presence, left the banks of seaweed and danced ecstatically on my body. As I sat in the hollow slapping my face and neck, the dichotomy between appearance and reality seemed to infold and disappear. One appearance was being replaced by another. Reality might be the sum of all possible appearances, some generated by science, some by art, some by psychosis; some known, some unknown, some unknowable. In that case it was forever out of reach. Or it might be an unbroken awareness of the content of consciousness, and of its nature, with one appearance being replaced by another: this was what I now meant by intimacy.

The oxymoronic violence I’d been subjected to since my fatal visit to the doctor had distracted me from pursuing this intimacy. At first, I glimpsed that my only chance of reconciling myself to the undistinguished heap of incidents which made up my life lay in that direction. But then I got caught up in Prozac and New York and gambling and Angelique and the mirage of love and money. Not to mention my scholarly efforts to understand the current consciousness debate, a debate which happens to contribute nothing to the resolution of the question.

I wondered again whether I should give up writing On the Train . It didn’t seem likely to bring me any closer to my objective. Maybe Patrick — who, strangely enough, also has cirrhosis — should carry the burden of some of the things that have started to take shape for me on the beach. When writers imagine a character who is dying, or condemned to die, they all too often make him ruminate about the past, worrying that he may not have led a good life, or being haunted by some forking in the road when he ran away from true love, or failed to save a friend’s life. Something with tons of flashbacks, and a big violin section. Either the character claims to have a few regrets but, then again, too few to mention after page 300, or he has the incredible courage and honesty to regret everything and wish he had not done it his way. In either case, the main feeling about dying, namely that it’s happening too soon, is blurred by a preoccupation with the past.

Well, those of us who are dying — as opposed to those who are lounging around in their studies making dinner engagements, and then reluctantly disconnecting the phone for twenty minutes in order to browse through a medical textbook and look up some realistic details — those of us who are really dying haven’t got time to ponder the past. The present is scintillating with horror and precision. The past is a luxury for people who think they have a future. Does my life have subtle connecting threads, strange coincidences, uniting themes? You’d better believe it. Things can’t help repeating themselves, can’t help colliding. That’s not meaning, it’s where the search for meaning begins.

I was beginning to feel cold and hungry, and tempted to return to the farmhouse, but I stayed crouched in the hollow, feeling there was something I had overlooked. And then I realized that beauty had seemed fundamental to me when I thought I was going to see my daughter. Now that I was not going to see her the conviction had deserted me. Sometimes the closest things are the hardest to see. I was shattered by the stupidity of not noticing that my whole outlook pivoted on my daughter. That feeling of panic and self-reproach when you realize, at exactly the moment you slam the front door closed, that you’ve left the keys inside, if it could be magnified a thousand times, would dimly resemble the electrocuting shame that rushed through me on the beach. Ton Len, I had forgotten Ton Len. When I saw her a year ago, she was lying on the sofa and I held her small feet completely in my hands and she smiled and looked at me with utter trust. She knew I’d always be there to look after her. That’s the picture that comes back to me again and again. The smile, the trust. I haven’t written about it, but then again there’s no mention of camels in the Koran. Some things are too flagrant to point out until they’ve shown a talent for hiding or getting lost. Last night I doubled my betrayal by losing sight of her. I will almost certainly die too soon to see her again and I am powerless to do anything about it.

And so I sat in the hollow, pinned down by the fascination of the way that everybody hurts each other by trying to make themselves happy. The pursuit of happiness is not so much an inalienable right as an inevitable disaster. I seemed to understand, without needing to formulate it, how things had come to be as they were, with my four-year-old daughter a thousand miles away, the memory of her father’s love drifting into the fog banks of early childhood and infancy, her mother in a tangle of hatred and spiritual ambition, and her hysterical and gloomy father fixed on a strangely academic obsession. All the players without any recourse to freedom. Locked.

I was stung by the irony of pursuing something I was calling intimacy, some relationship with mental reality which I hadn’t yet defined but was already invoking like a mantra, when the ordinary intimacy of contact with the person I loved most was absent from my life. I could sense a chain-mail landscape receding infinitely in every direction. Each generation linked by steel. Everyone acting under the duress of circumstance and personality. What did it mean to be free in this situation? Did I have to content myself with amor fati , the love of fate, doing willingly what I must do anyway? Was that it? I noticed that I was not breathing and started again hastily. I stopped slapping my face and neck. My hands dropped to my side. If I wanted intimacy I could have it with the sandflies.

Читать дальше