“You think I don’t know how to clean?”

“I didn’t say that.”

“You’ll see. Next time you come —” I break off, thinking. “When is the next time?”

He picks up a manual and slowly flips through pages that are thin as onionskin. “I will be back in April.”

“Five months.”

He nods. “And even then the winter will not be over. The winters are very long up here.”

“So everybody keeps saying. But that’s why I came — for the winter.”

He seems to lose patience, letting his breath out fast and turning towards the window, then he checks himself and looks at me steadily, sideways-on. “There are things you can’t tell me.”

Startled, I’m reminded of Adefemi, and how he used to talk sometimes. Somewhere there’s another version of us that got married, and had children, and lived together for the rest of our lives , he told me on the night we agreed to separate. He would say things that were so perceptive, so right , that I would gaze at him with eyes that felt wide and liquid, like a Manga girl, but he never seemed to appreciate the significance or value of his words, and he wouldn’t be able to remember them afterwards, nor would he have any idea of the effect they had on me. They were involuntary and obvious — to him, at least — and it was in his nature to allow them to pass through him. He was thriftless in that way. Axelsen, also, doesn’t seem to be entirely in control of what he’s saying. It’s as if he knows something he should not know. As if he momentarily became a medium. He even looks slightly dazed, like someone waking from a trance.

“I brought you something.” He opens a cupboard, takes out a flat package, and hands it to me. The wrapping paper has Santas on it.

I smile. “Christmas is early this year.”

“It was the only paper I could find.”

I tear off the wrapping. Inside is a red hot-water bottle, just like the one my mother used to put in my bed when I was little. I feel tears coming.

“Did I do something wrong?” Axelsen asks.

“No, no. It’s all right.” I sniff, then wipe my eyes. “I haven’t seen one of these for years.”

“Just something for the winter.”

“So you knew all along. You knew I wasn’t going to change my mind.”

“Sometimes, if you do one thing, you can make the other thing happen.”

I understand the principle. Like the opposite of tempting fate.

“I’m sorry it didn’t work,” I say. “But thank you, anyway. It’s a lovely thought.”

He looks away from me, adjusts his baseball cap.

“What’s your first name?” I ask.

“Olav.”

I step back, towards the door. “Enjoy the winter, Olav. I’ll see you in April.”

“And your name?” he says. “You won’t tell me your name?”

“I’ll tell you — on one condition.”

Folding his arms, Olav turns back into a figure of authority — decisive, unruffled.

“If somebody asks about me,” I say, “or shows you a photo of me, you must say you haven’t seen me.”

“What if it’s the police?”

Once again he catches me off guard but I don’t hesitate. “You haven’t seen me. It doesn’t matter who it is.” I pause. “You have to promise.”

“That’s a big condition.”

But he promises, and so I tell him.

“Misty?” he says in a voice that suggests he would never have guessed. “It sounds like a country-and-western singer.”

A boat on a lake, three men in tartan shirts. My mother up on her feet, singing Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose …

Lights glittering all along the shore.

Then later, in a motel outside Milan, a man shouting, Maledetta putana , in the car park at four a.m., and my mother murmuring, Go back to sleep, darling , and then, half to herself, It’s just some drunk .

“Do you like country-and-western?” I ask Olav.

“Actually, I do — and Röyksopp.”

“I’m sorry?”

He grins. “It’s Norwegian music.”

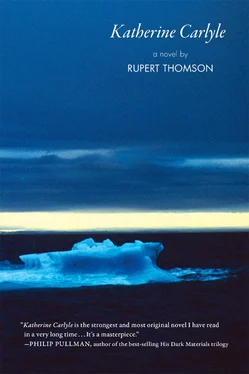

Later, back in my room, I wonder why I didn’t tell him who I was. I owed him the truth — surely. But perhaps I didn’t feel I could bank on the fact that such an honest straightforward man would lie successfully on my behalf. At least now, if someone asks him about Katherine Carlyle, he can say, with his hand on his heart, that he has never heard of me.

/

I gaze down at the dull pewter-colored key Zhenya gave me, unmarked except for an unevenly stamped number. A few weeks ago, Klaus asked me what I was doing in Berlin and I told him, rather pretentiously, that I was “experimenting with coincidence,” and now, as I stand in the corridor outside Mrs. Kovalenka’s apartment, the walls a hospital green, the air smelling of reheated food, I realize my idea has become a reality. I would prefer her departure to have been less traumatic — a lottery win; a golden handshake at the very least — but once again I have the impression that I only have to apply the slightest pressure to the fabric of the world and it will give. It’s as though I forged the key through sheer force of will; I wanted it so much that it came into being. Is it any wonder I feel powerful? I haven’t met the cleaning lady, and probably never will, yet I’m about to wrap the remnants of her life about me like a cloak. I could take her name, adopt a new persona. Complete my disappearance. Misty Kovalenka : less like a country-and-western singer than an ice-skater or a tennis star.

Facing the stairwell, Mrs. Kovalenka’s cheap wooden front door has been treated with a clear varnish and fitted with a Judas eye. I insert the key into the lock and feel it engage. The door clicks open. A gust of air moves through the gap like someone breathing out. A final sour exhalation. The door’s bottom edge catches on the floor as I enter, and I have to push it with both hands. Expecting similar resistance when I close it, I give it a good shove. It slams loudly, then stares at me with its Judas eye. What?

Inside the apartment it’s colder than in the stairwell, so cold that I can’t smell anything. The hallway is L-shaped, with a glass light shade in the ceiling. Just inside the front door, on the left, is a windowless kitchen, its walls the scorched yellow-brown of nicotine-stained fingers. A half-full glass of tea in an ornate metal holder stands on a work surface. I open a cupboard. A jar of pickled mushrooms, a tin of sprats. A few packets of rice and crackers. At the end of the hallway or corridor, on top of a chest of drawers, is a kind of shrine, with china animals, church candles, and a tin jug filled with plastic flowers. Tacked to the wall above is a picture of Jesus, his soulful eyes gazing skywards, a red heart bleeding through his robes. There’s also a photo of Putin, cut from a magazine, and one of Marcello Mastroianni, as he appeared in La Dolce Vita . The bathroom, which is also on the left, has the white-tiled walls and floor of a slaughterhouse. The mirror above the sink is cracked, but the tube of toothpaste on the shelf below has been carefully rolled from the bottom and isn’t quite empty. A pink towel hangs on a rail. One moment I feel like a detective, clear-eyed, forensic, looking for evidence or clues. The next, I’m one of Mrs. Kovalenka’s relatives, feeling for her. Missing her. I asked Zhenya about the cleaning lady but she didn’t give too much away. Quiet, she said. Lived alone.

On the other side of the corridor are two more rooms. The bedroom isn’t much bigger than the kitchen, with a single bed and a wardrobe, and the walls are papered with a recurring pattern of blue flowers and brown autumn leaves. On the bedside table is a cheap alarm clock, a pair of glasses, a radio, and several bottles of pills. The clock is half an hour slow. The window overlooks the football pitch and the road that leads to the heliport. A renovated apartment block stands on the high ground to the right, snow piled at its base in dirty sculpted heaps. I face back into the room. Open the wardrobe. Enclosed in see-through plastic is a jacket and skirt of a synthetic green material, which Mrs. Kovalenka probably kept for special occasions. At the bottom is a pair of fur-lined ankle boots worn down at the heel. I have a flickering sense of the woman, a twinkly, half-suggested image, like a hologram. She keeps her own company and doesn’t ask for much. I wonder what brought her to this place. I wonder if she’ll survive.

Читать дальше