But I do understand. The blacks are taking over.

The row of shops is completely dark. Sodding hell, George hasn’t sodding got there. Left me locked out in the sodding rain. The sodding frigging soaking rain. Like a dog or cat left out to drown. My head gets cold now my hair’s so short –

Mum’s not keen on my hair being short. ‘It’s your good point, your hair-colour,’ she says. As though it was my only one. ‘That horrible crewcut makes you look bald. There’s enough men have to be bald. You don’t.’

My dad was actually there when she said that. Mum’s always on at me not to be rude, but how about that from Mrs Manners? My dad’s going bald as a cricket ball.

Seems to me women think men don’t have feelings. They get together and go on about us and laugh and try to make us feel small … Mum and Shirley, out in the kitchen. It was always like that: Us and Them.

Come on George, you frigging bastard. I’m dying out here in the rain on my own. I haven’t even had a cup of coffee. While bloody old George is on his first two fags, hacking and puking in the back of the car as his ugly fat bitch of a wife drives him over.

George keeps on about visiting Dad. ‘Just say the word, and Ruby’ll bring me. We’re waiting for the word, my boy.’

‘You’re not allowed to smoke, in a hospital.’

‘Do you think I’m unacquainted with hospitals?’

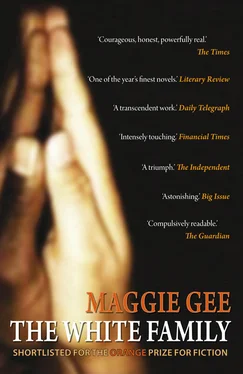

He talks like someone from a book. I don’t know what he’s going on about, half the time. He’s keen on books, or the idea of books. He actually thought we could sell some here! They ended in a bin, marked ‘3 for 20p’, and we still couldn’t sodding get rid of them. And these were great writers — Dick Francis, Jackie Collins! There aren’t a lot of book readers, round here.

He’s past it, really, a long way past it, but he won’t give up, he leans on me. I carry that man. I carry his shop. And I still can’t frigging get in in the mornings.

Ah, there he is. St Fucking George. Half-falling out of the car, good, bumping his great fat knee on the door. Then the rest of his body, a sack of lard. ‘It’s wet, in case you haven’t noticed.’

‘Sorry, sorry. We had an attack. We soldier on, but —’ The rest of what he said was drowned in a horrible sickbag of coughing and gasping.

What I put up with. I’m a hero, really. Never mind George, I deserve a saintdom. I am a saint already. St Dirk.

Silly bloody name that woman gave me.

Something’s up. Maybe George is dying. He’s definitely being funny with me. Less rude than usual. Almost pleasant. As long as he’s managed to do his will …

Mum thinks he’s going to leave me the shop. It belongs to him, not rented or anything. George’s parents lived over the shop. Now they rent out upstairs for good money, which is handy because the shop doesn’t make a lot. (It could do. Would do. If I was boss.) They live with Ruby’s mother, who’s ancient. She’s going to be a hundred next year.

I want my dad to live to a hundred. I want my dad to go on and on. I used to pop into the Park on my lunch-break and eat my sandwiches with him. It felt good, being with the Park Keeper. Being with the man in charge …

Dad is my other claim to fame. As well as my brother, who’s more — world -famous. Different kind of fame, isn’t it, really? They’d never think of having Dad on the telly, but everyone round here knows Dad. And I’m his son. And Darren’s brother. We’ve got a lot of go, in my family. And I shall be someone. I’ll make my mark. I shall get into the history books. Carve my name. Carve my name with — whatever. I’m good with words, but sometimes they escape me.

I’d like Mum to be proud of me. And Shirley (then she would be sorry). I could be their claim to fame. ‘White, the millionaire businessman.’

Mum must be right that I’ll get the shop. George hates me, but he hates the Pakis worse. The Pakis will never get this shop. They try it on, and he just says ‘No’. He doesn’t even like them coming in to buy papers. When they did, he talked about them under his breath. Swearing till even I got embarrassed.

Now I’d never do that, personally. Doesn’t make sense. You want their money, so shut up about them until they’re out of earshot. As customers, they aren’t that bad. At least they’ve got money, which the blacks rarely do. Not that you see them spending it here.

Just the businessmen in pin-striped suits, funny little brown men with thick hair in long haircuts, grinning at me and asking for George, and they go behind the counter with their briefcases and shut themselves up in the room at the back which I couldn’t stay in for more than ten seconds without throwing up because it stinks of George, of sweat and sweets and Players’ Navy Cuts, and after twenty minutes or so George starts shouting, George starts swearing and shouting a bit and they all pile out, still very smooth, the Pakis, smiling at him, smiling at me. Grinning, grinning as if they were winning. But I know he hates them. I know he won’t sell.

‘I’m playing a little game with them,’ he explained to me, the week before last. ‘I’m having a little game with our friends. Our coloured friends. It’s an amusement.’

‘How do you mean, amusement?’ I asked. ‘I thought you couldn’t stand them in your shop. Now they’re always round here. Oiling and mincing. They stink of aftershave. They’re poofs. They are, all Paki men are poofs.’

Just once in a while we have a laugh, and I think old George is not so bad.

Not that I’m joking. Pakis are poofs.

I hate him most first thing in the morning. Like now. When George is just sitting there smoking and choking and I’m shitting bricks getting everything done. And he always has to criticize, doesn’t he. ‘You’re not going to put those there, are you? Are you?’ Yet he does nothing. I mean nothing . Doesn’t even serve the customers now, the early ones who come in while I’m busy. He says he’s too slow to get to the till. Too fat, he means. Too idle, he means. So he’s sitting there putting all his effort into breathing. In, out, like a very slow saw. While I’m cutting the bundles of papers undone. And getting the van-drivers to take the returns. And checking to see the numbers are right. And seeing the supplements are in. And putting the papers out on the shelf, upside down because the mean old bugger is terrified of people reading headlines for free. And pulling out Hello! and Take a Break! and Woman to sit in our premier selling slots. And sorting out papers for the smelly little wanker who goes round shutting his fingers in letter-boxes. Harry Rutter, the paper-boy. And giving him a hard time if he’s late. (That was me, wasn’t it, for years and years? So maybe things are on the up, after all. Maybe Dirk White is on his way.)

But George is still sitting there, lighting up another.

Careful, fat-face. Don’t tire your wrist. Why not just stuff the whole pack down your throat, then chuck a lighted match down after it?

George will snuff it, and I’ll inherit. And get the shop the way I want. Bring the shop into the twenty-first century.

Which is going to be big for paper-shops, believe me. Forward-looking paper-shops. Shops that have got a bit of go. Ours hasn’t, at the moment, but that’s down to George.

Think videos.

Think Lottery.

Think Fax and Internet.

Especially the net. The Thing of the Future (We’ll advertise. Think money. Think big!) Because lots of people won’t have their own computer. And that’s where we’ll come in. With ours. Laughing. They’ll put money in the slot for quarter of an hour or however long they need to get what they want. A line of computers, a line of chairs. I can see it clearly. Smart … red chairs. And coffee. And snacks. As long as Mum doesn’t make them.

Читать дальше