***

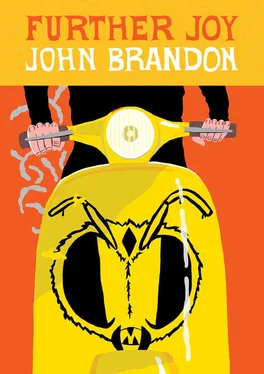

After the game had been lost, Marky mounted his scooter — a wood-framed chopper with angry bees painted all over it — and whined out of the swampland and away from the diamond. Marky had found the scooter near the railroad tracks and had it overhauled by the trade school mechanics, who’d made it too powerful for its own good. He stayed in third gear all the way to Hurley’s house.

Hurley was in the custom musical instrument trade, among other things, and Marky needed a one-of-a-kind bass drum for a band he wanted to manage. He had known the guys in the band awhile; they were a few years older than him, upperclassmen at the local high school. Their band was called Some Cars Are Trucks; it featured a genius on harmonica but suffered from a dearth of thump and an even more alarming dearth of gimmick. Marky figured the absurd drum would get the band noticed, make them memorable, and from there talent could take over. The vast majority of bands wound up fizzling and breaking up, Marky knew, but he thought he might as well try to jumpstart these guys and if anything happened he’d be in for ten percent. The harmonica player really was amazing, and the band’s songs were sad but not too sad.

He stepped high through some weeds and then scaled the manmade hill Hurley’s house perched atop. He knocked on Hurley’s door and it opened instantly. The man seemed older than Marky remembered — bearded, wearing a tennis outfit, snapping his fingers in thought.

“Marky,” Marky said.

“Oh, I know. I like to see how people say their own names. Are you a Scotch drinker?”

“No, not really,” Marky admitted.

“I know. I’m kidding with you. You’re a teenager, you probably only drink beer.”

“Nothing right now, thanks. I’m kind of on a schedule today.”

Marky got a look at the living room, cluttered with record players and stacked terrariums, then Hurley ushered him down to the basement, which was twice the size of the house and was divided here and there by hung tablecloths. Basements were rare in Florida, and being in this one made Marky a little nervous. It held racquet-stringing equipment, painted steel barrels, and plain tables to which vices clung. Marky was still wearing his cleats, and he stepped gingerly on the concrete floor.

“Can’t light up down here,” Hurley said.

“That’s okay, I don’t smoke.”

“Don’t drink, don’t smoke. You sure you’re a teenager?”

“Basically,” said Marky. “I’m on deck to be a teenager.”

“Hey, before I forget to tell you, I’m getting a bunch of books in next week. You should come back and take a look. I’m going to price them at a penny a page.”

“Where are they from?”

“They were trying to start a college over in Redleg, but the money fell through.”

“Oh, I heard about that,” Marky said. “That Bible college.”

“A couple of them I’m keeping. There’s one all about how kings used to blind architects so they couldn’t build the same castle for anyone else. Or cathedral or whatever. And there’s one on carnivorous plants. Now that’s a poker face — a hunter that has to have the prey land on him.”

Marky nodded, holding an appreciative look on his face. After a moment he said, “Anyway, that bass drum. We talked about it at the pancake breakfast.”

Hurley bared his teeth, as if for inspection.

“Twelve foot across,” said Marky.

“Now if it’s too big, you won’t be able to hear it.”

“Really?” Marky asked. “Why, too low a register?”

Hurley looked off, skeptical of his own assertion. “Well, no. I guess you’d hear it. You’re going to hear it and also feel it.”

“Ever make one that big?”

“No, I made a pretty big one for some people holding a parade once, but not twelve foot. Made a lot of stuff for those guys. Parades used to be much better than they are now.”

“The ones I’ve seen have been lame,” Marky agreed.

“You missed out on a lot of Golden Ages, and the Golden Age of parades is one of them.”

Marky tried to think of something that was enjoying its Golden Age right now. There had to be something. He had the sensation, in this basement, that he was being filmed.

“I ever tell you about the radio station I used to own?” asked Hurley.

“Yeah,” Marky answered. Maybe Hurley had told him about the radio station and maybe he hadn’t. Marky couldn’t remember. “I don’t mean to be in a rush, but I was hoping to get a price from you and scoot on.”

“Oh, for sure,” Hurley said. “On the run. I know.” He ducked behind a curtain then reappeared with a form, which read:

CUSTOM TANK

CUSTOM RACKET

CUSTOM INSTRUMENT*

If ___________________ cannot be delivered by ___________________, the sum of ___________________ will be refunded in full to ___________________.

X ___________________

X ___________________

“Waterproofing’s extra,” Hurley said. He pulled a calculator from somewhere.

“Let’s just skip that.”

“Moisture can kill a drum. Getting caught out in the rain. Or just the humidity on a porch, even. It can totally dull the sound.”

“Yeah, I think I’ll do without it, though,” said Marky. “These guys rehearse at the community college. They should be fine.”

“You may regret that, little dude. I don’t sell insurance for these things.”

“I don’t buy insurance. I’m not sure I believe in it, actually.”

Hurley took a retreating step, then for effect he took another. “That’s badass,” he said. “Tattoos and gangster rap, those are just products. Refusing insurance is badass shit.”

Marky leaned his scooter in his uncle’s garage, removed his cleats, and went in for a bowl of cereal. It was his uncle’s naptime so he turned the TV on low, to a program about the strange things people ate in Asia. Marky’s uncle collected antique pornography and had stacks of calendars and prints all over the coffee table. These pale, resigned, full-bodied ladies were more nurturing than seductive. Marky could imagine them eating peanut butter right out of the jar with spoons as big as hairbrushes, carrying hefty pens around in their hands all day, no intention of writing. His uncle collected all sorts of things. They lived among chili recipes and old car phones.

Marky knew that the man wasn’t a loved figure up at the warehouse where he worked the evening shift. His uncle carried on a handful of feuds with various coworkers and called in sick the maximum it was allowed. The warehouse, which stored mainly hair products, was going to be bought out — according to the gossip it was all but a done deal — and no one expected Marky’s uncle to survive the changeover. He wasn’t skilled, didn’t have a forklift license or anything. He’d only gotten the job in the first place because one of the shift supervisors had been an old friend of Marky’s uncle’s mother, before she died. Marky’s uncle never stayed at a job more than a year or two, but it was getting harder for him to get hired anywhere — the economy, and the fact that he had a reputation by now.

The topic of Marky’s uncle’s precarious employment wasn’t spoken of in the house, but there was a tension all could feel. The factory could be bought out next week, next month. Marky’s uncle, on principle, wouldn’t accept unemployment checks. He’d wind up in the temporary labor line, most probably, with the convicts and community college washouts, and the thought of that sank Marky’s heart.

A shot was fired and Marky dropped the hosiery calendar he’d been holding into a splay on the rug. His cousin was shooting.

Marky went out the back, toward the little range his cousin had cut near the fill dunes. His cousin was seventeen and even less suited for this world than the uncle. Marky’s cousin was a poet who spent most of his time observing birds and practicing with weapons. He was shooting cans of powdered barbecue sauce with a gun called a Mini-14. The concentrated powder, infused with calcium and ginkgo biloba, had been a science project of Marky’s. Marky didn’t want to startle his cousin, so he sat on a shellacked stump and watched can after can become dust in the breeze.

Читать дальше