Around the middle of October, they started selling boza once more. Mevlut thought it would be best to get rid of the sandwiches, biscuits, chocolates, and other summer offerings and concen trate only on the boza, cinnamon, and toasted chickpeas, but as usual he was being overly optimistic, and they didn’t listen anyway. Once or twice a week, he would leave the shop to Ferhat in the evening and go out to deliver boza to his regular customers. The war in the east meant that there were explosions all over Istanbul, protest marches, and newspaper offices bombed in the night, but people still thronged to Beyoğlu.

Around the middle of October, they started selling boza once more. Mevlut thought it would be best to get rid of the sandwiches, biscuits, chocolates, and other summer offerings and concen trate only on the boza, cinnamon, and toasted chickpeas, but as usual he was being overly optimistic, and they didn’t listen anyway. Once or twice a week, he would leave the shop to Ferhat in the evening and go out to deliver boza to his regular customers. The war in the east meant that there were explosions all over Istanbul, protest marches, and newspaper offices bombed in the night, but people still thronged to Beyoğlu.

At the end of November, a devout key cutter across the road told Mevlut that a newspaper called the Righteous Path had written something about their shop. Mevlut rushed to the kiosk on İstiklal Avenue. Back in the shop, he sat down with Rayiha and examined every inch of the paper.

There was a column under the heading “Three New Shops,” which started off with praise for Brothers-in-Law, followed by some words on a new kebab-wrap shop in Nişantaşı and a place in Karaköy selling rosewater and milk-soaked Ramadan pastry and aşure, the traditional pudding of fruits and nuts: keeping our ancient traditions alive, rather than discarding them to imitate the West, was a sacred duty, like honoring our ancestors; if, as a civilization, we wanted to preserve our national character, our ideals, and our beliefs, we had to learn, first and foremost, how to remain true to our traditional food and drink.

As soon as Ferhat came in that evening, Mevlut was very excited to show him the newspaper. He claimed it had brought in loads of new customers.

“Oh, drop it,” said Ferhat. “No one reading the Righteous Path is going to come to our shop. They haven’t even included our address. I can’t believe we’re being used as propaganda for some disgusting Islamist rag.”

Mevlut hadn’t realized that the Righteous Path was a religious newspaper, or that the column was a piece of Islamist propaganda.

When he realized that his friend wasn’t following what he was saying, Ferhat lost his patience. He picked up the newspaper. “Just look at these headlines: The Holy Hamza and the Battle of Uhud…Fate, Intent, and Free Will in Islam…Why the Hajj is a Religious Duty…”

So was it wrong to talk about these things? The Holy Guide spoke beautifully on all these subjects, and Mevlut had always enjoyed his talks. Thank God he’d never told Ferhat about visiting with the Holy Guide. His friend might have branded Mevlut a “disgusting Islamist,” too.

Ferhat continued to rage his way through the pages of the Righteous Path: “ ‘What did Fahrettin Pasha do to the spy and sexual deviant Lawrence?’ ‘The Freemasons, the CIA, and the Reds.’ ‘English human rights activist is found out to be a Jew!’ ”

Thank God Mevlut had never told the Holy Guide that his business partner was an Alevi. The Holy Guide thought Mevlut worked with a normal Sunni Turk, and whenever their conversations touched upon Alevis, the Shias in Iran, and the caliph Ali, Mevlut always changed the subject immediately lest he have to hear the Holy Guide say anything bad about them.

“ ‘Full-color annotated Koran with protective dust jacket for just thirty coupons from the Righteous Path, ’ ” read Ferhat. “You know, if these people take power, the first thing they’ll do is ban the street vendors, just the way they did in Iran. They might even hang one or two like you.”

“No way,” said Mevlut. “Boza ’ s alcoholic, but do you see anyone bothering me about it?”

“That’s because there’s barely any alcohol in it,” said Ferhat.

“Oh, of course, boza’s worthless next to your Club Rakı,” said Mevlut.

“Wait, so you have a problem with rakı now? If it’s a sin to touch alcohol, it doesn’t matter how much there is in your drink. We would have to close this shop down.”

Mevlut felt the hint of a threat. After all, it was thanks to Ferhat’s money that they had this shop in the first place.

“I bet you even voted for these Islamists.”

“No, I didn’t,” Mevlut lied.

“Oh, do whatever you want with your vote,” said Ferhat in a condescending tone.

There followed a period of mutual resentment. For a while, Ferhat stopped coming by in the evenings. This meant Mevlut couldn’t leave the shop to deliver boza to his old customers and that, during quiet spells when no one came by, he got bored. He never used to get bored when he sold boza out in the city at night, not even in the emptiest street where no one ever opened any windows or bought any boza. Walking fueled his imagination and reminded him that there was another realm within our world, hidden away behind the walls of a mosque, in a collapsing wooden mansion, or inside a cemetery.

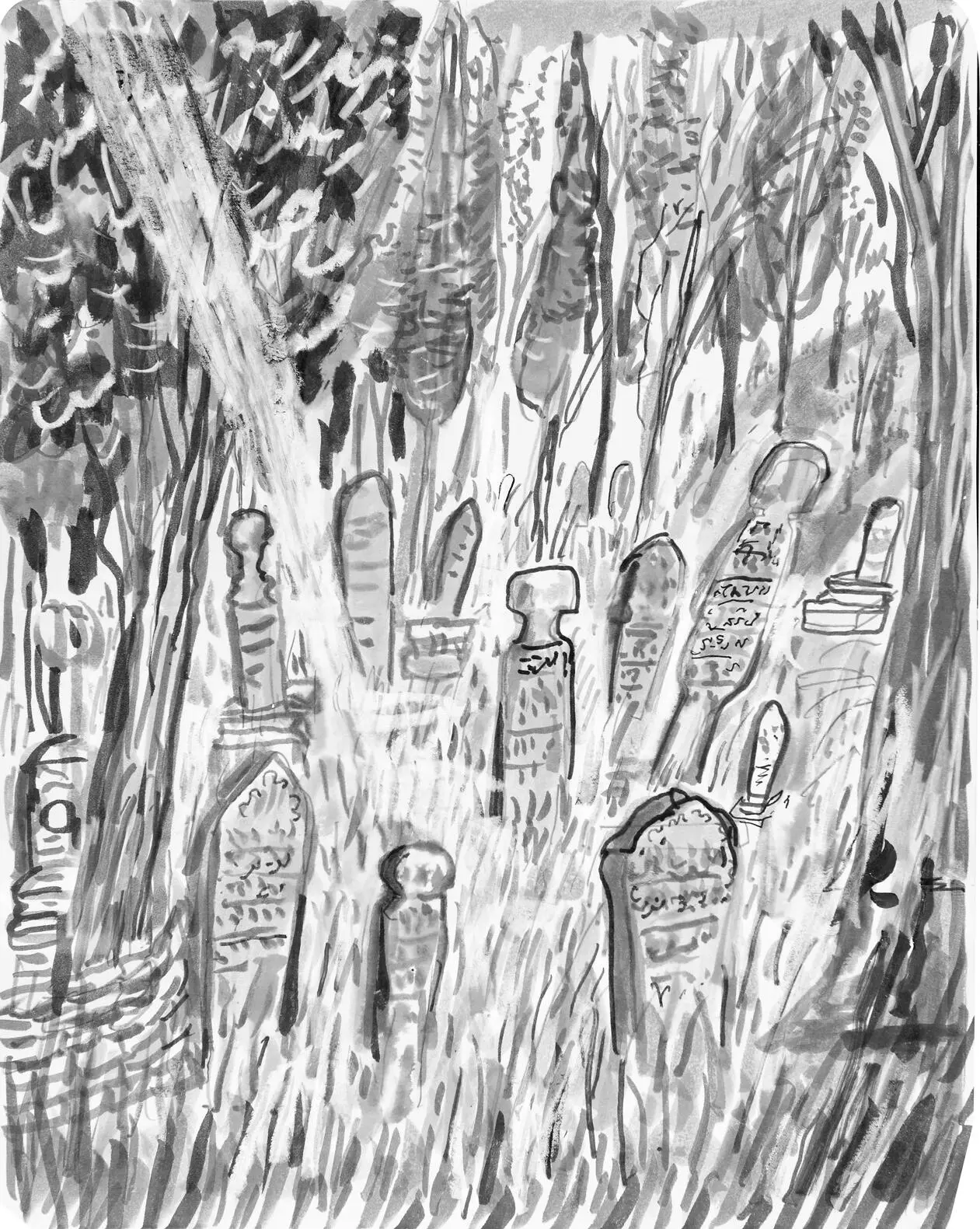

The Righteous Path had published a picture of this world as it existed in Mevlut’s mind. The image illustrated a series of articles entitled “The Other Realm.” When he was alone in the shop at night, Mevlut would pick up the newspaper that had written about Brothers-in-Law and open it up to the page with this picture.

Why were the gravestones keeling over? Why were they all different, some of them sloped sideways in sorrow? What was that whiteness coming down from above like a divine light? Why did old things and cypress trees always make Mevlut feel so good?

2. In the Little Shop with Two Women

Other Meters and Other Families

Rayiha.Samiha is still as beautiful as ever. In the mornings, some men get disrespectful and try to touch her fingers while she’s handing them their change. So now we’ve started putting people’s money down on the glass counter rather than giving it to them directly. I’m usually the one who prepares the ayran, as well as the boza, but when I look after the cash register no one ever bothers me. A whole morning can go by without a single person coming in to sit down. Sometimes we get an old lady who sits as close to the electric heater as she can and asks for a tea. That’s how we started serving tea, too. There was also this very beautiful lady who went out shopping in Beyoğlu every day and came in sometimes. “You two are sisters, aren’t you?” she used to ask, smiling at us. “You look alike. So tell me, who’s got the good husband, and who’s got the bad one?”

Once, this brute with a face like a criminal came in with a cigarette in his hand, asking for boza early in the morning, and after he’d downed three glasses, he kept staring at Samiha saying, “Is there alcohol in boza, or is something else making my head spin?” It really is difficult to run the shop without a man there. But Samiha never told Ferhat, and I didn’t tell Mevlut either.

Sometimes Samiha would drop everything and say, “I’m off, you’ll look after that woman at the table and take care of the empty glasses, won’t you?” As if she owned the place and I was just some waitress…Did she even realize that she was trying to sound like one of those wealthy ladies whose homes she used to clean? Sometimes I’d go to their house in Firuzağa and find that Ferhat had already left a while ago. “Let’s go to the cinema, Rayiha,” Samiha would say. Or we would watch TV. Sometimes she sat at her new dressing table and did her makeup while I watched. “Come and put some on,” she’d say, laughing at me in the mirror. “Don’t worry, I won’t tell Mevlut.” What did she mean by that? Did she talk to Mevlut when I wasn’t in the shop, and was it me they spoke about? I was so touchy, so jealous, and always close to tears.

Читать дальше

Around the middle of October, they started selling boza once more. Mevlut thought it would be best to get rid of the sandwiches, biscuits, chocolates, and other summer offerings and concen trate only on the boza, cinnamon, and toasted chickpeas, but as usual he was being overly optimistic, and they didn’t listen anyway. Once or twice a week, he would leave the shop to Ferhat in the evening and go out to deliver boza to his regular customers. The war in the east meant that there were explosions all over Istanbul, protest marches, and newspaper offices bombed in the night, but people still thronged to Beyoğlu.

Around the middle of October, they started selling boza once more. Mevlut thought it would be best to get rid of the sandwiches, biscuits, chocolates, and other summer offerings and concen trate only on the boza, cinnamon, and toasted chickpeas, but as usual he was being overly optimistic, and they didn’t listen anyway. Once or twice a week, he would leave the shop to Ferhat in the evening and go out to deliver boza to his regular customers. The war in the east meant that there were explosions all over Istanbul, protest marches, and newspaper offices bombed in the night, but people still thronged to Beyoğlu.

![Джон Харгрейв - Mind Hacking [How to Change Your Mind for Good in 21 Days]](/books/404192/dzhon-hargrejv-mind-hacking-how-to-change-your-min-thumb.webp)