‘The man who had invited me in said, “We’ve got a visitor”, and the strangest thing happened. A head raised itself from in amongst the mess on the table and looked at me. There was so much chaos I hadn’t noticed a man asleep in the middle of it. Like I told you, I’d lived in Glasgow all my life up until then. I’d seen plenty of men with scars on their faces, but this one was a humdinger.’

‘A Colgate smile.’

It was as if Mrs Dunn had forgotten he was a doctor of literature. Her voice held a warning note.

‘I wouldn’t joke about it, son.’

Murray said, ‘I went to his funeral the other week,’ like it was some kind of reparation for his lapse in taste. ‘I’m afraid it wasn’t very well-attended.’

Mrs Dunn nodded, taking the empty pews in her stride, and went on with her story.

‘I was standing in a block of sunshine by the open door. I could still feel the warmth on my back and hear the birds singing outside, but beyond that small shaft of light, it was a different world. Some of those stories and songs I’d heard at the ceilidhs must have stuck, because I remembered tales of people getting lost in the faery hills. The faeries lay on a fabulous evening of feasting, drinking and dancing, and next morning set their guest on the right path for home. But when they arrive back in the village, the poor soul discovers a hundred years have passed and all their kin are long dead.’

Murray said, ‘When seven lang years had come and fled, / when grief was calm, and hope was dead; / when scarce was remembered Kilmeny’s name, / late in a gloamin’ Kilmeny came hame.’

‘You would have fitted in well at the ceilidhs, Dr Watson. I felt like Kilmeny herself, too fascinated to turn for home. The one I’d met first said, “Let’s have some of your famous tea, Bobby.” And the other one jumped to his feet, though he’d looked half-dead the moment before. Suddenly I realised they were not much more than boys and felt annoyed at myself for being such a teuchter. I think that was one of my great fears, you see, that I would lose my so-called sophistication and end up a wee island wifie.’

The lights shone warmly in the sitting room and it was only when Mrs Dunn rose and drew the curtains that Murray realised the world outside the window had descended into darkness. Archie the cat stood up in Murray’s lap, raised his tail and presented an eye-line view of the tiny arsehole set in the centre of his lean rump. He jumped elegantly to the ground. Mrs Dunn opened the living-room door and he slid through, tail as straight as a warning flag.

‘As soon as he hears me closing the curtains, that’s him out for the night, hunting.’

‘I guess the pickings are better after dark.’

‘For some things.’

‘It was sunny the day you went to visit Christie.’

Mrs Dunn hesitated, as if reluctant to return to her tale.

‘Scorching. The man I had met outside introduced himself. It turned out he wasn’t Archie at all, but a friend of his. .’

Murray knew the name was coming, but it was still a shock to hear it on her lips.

‘. . Fergus. The other one, the one with the scar, was Bobby. He came back with the water and said, “It was time for a brew anyway.”’ Mrs Dunn lifted her glass of whisky, and rested it on the embroidered antimacassar on the arm of her chair, gazing at it as if she could see the scene in its tawny depths. ‘I was nervous, sitting there with two men I didn’t know, even though they weren’t much more than boys. But the door was still open, the daylight still shining in from outside, so I told myself to relax and stop being such a baby. Fergus did most of the talking. I wouldn’t have entertained him if I’d been on the mainland. He was the kind of lad me and my pals would have laughed at, a bit of a snob, I suppose. But it was nice to have company of my own age, even if he wasn’t talking about the kind of things people our age usually talked about.’

‘What did he talk about?’

‘Poetry, I think. Remember, I’d got used to being in company where I didn’t understand half of what was being said. The other one, Bobby, put the tea in front of me. It was like no tea I’d ever seen before.’ Mrs Dunn broke off and looked at Murray. ‘You’ll be less naïve than I was back then, Dr Watson.’ She gave a small laugh. ‘I’m less naïve than I was back then, but they were simpler times. I got the cake out of my bag. It seemed a shame not to share it with them. Anyway, I had a feeling I’d need something sweet to help me get that brew down. And I was determined to get it down. It’s amazing what folk will do for politeness’ sake.’ Mrs Dunn straightened herself in her chair and smoothed her skirt beneath her hands, though there was barely a crease in it. ‘The two boys held their noses and drank up. I thought, this is funny tea this, but Fergus said, “It’s a herbal infusion, extremely efficacious. Christie introduced us to it.”’ That was the way he talked. But I thought, oh well, if it’s good enough for Christie, it’s good enough for me, and swallowed the lot.’ She took a sip of spirit as if hoping to banish the memory of the awful drink. ‘At first it was wonderful. Three children and all these years later, I can still recall the sensation. I never experienced anything else like it. The pair of them ate the cake like they hadn’t had a decent meal in days.’ She looked him in the eye. ‘A bit like the way you ate the cakes I gave you this afternoon. But it seemed so funny the way they wolfed it down. I started to laugh, then found I couldn’t stop. It didn’t matter, because they were laughing too. I’m not sure how long we sat there, laughing over nothing.’ She took another sip of her drink. ‘What happened next happened gradually, the way the sea sometimes changes colour. It can be the brightest blue, and then, without you seeing where the change came from, the waters turn to grey. You look at the skies overhead and realise the whole scene has transformed and you could be in a different day from the one you were in, a different world.’

Murray kept his own voice calm, unsure of what he was about to hear.

‘That’s the way it is in Scotland.’

Mrs Dunn looked away from him, towards the curtained window.

‘It crept up on me like that. A feeling of dread. Then suddenly, I was terrified.’

‘Of the two men?’

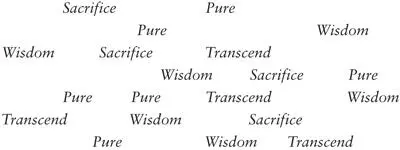

‘Of the men, the room, my own hands, the grass outside, the sound of the birds. I’d been fascinated by the books, now I could see bright shadows of them, little diamonds floating in the air, as dazzling as the stained glass in St Mungo’s when the sun’s behind it. It should have been beautiful, but it was too strange. I’d thought I was going mad, alone without John in the cottage, now I knew that I was. Fergus and Bobby were still talking, but I had no idea of what they were saying. It was as if their sentences were overlapping and repeating. I would hear the same word recurring over and over again, but not the word that came before or the ones that came after.’ Her voice rose and fell as she repeated the words in a far-away chant,

‘I’d thought I was Red Riding Hood, now I was Alice fallen down the white rabbit’s burrow. I wanted to ask if it was a poem, but I couldn’t because worse than the strange sounds and moving colours was the fear. It paralysed me. I tried closing my eyes, but the shapes were still there, organising themselves into patterns behind my eyes. Did you ever have a kaleidoscope as a child?’

‘Yes.’

‘I didn’t. Maybe they weren’t invented, or maybe they were too expensive in those days for the likes of us, but years later my daughter Jennifer got one in a present. I took a wee look through it and felt like I was going to be sick.’

Читать дальше