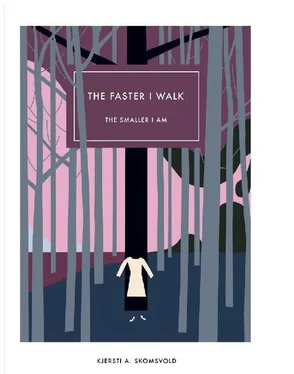

I NEED TO GO to the store and buy sugar in case June comes to “borrow” more. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t hope to meet the man without a watch on the way. Before I go, I spray on perfume, but this time I just squirt myself behind the knees. And a few drops behind the ears. And one squirt in the air in front of me as I’m walking.

When I reach the woods, he’s there, as if by appointment, and I know that this is the chance I’ve been waiting for. June’s visit gave me the self-confidence I needed, the man on the path obviously isn’t quite all there, therefore I can talk to him. Now all I need is something to say. Quickly.

“Hi,” I say. It’s as if I’m listening to a stranger’s voice.

His expression doesn’t change.

“Do you think it’s nice here?” I ask.

He doesn’t answer.

“Yes, it’s nice here,” I say.

“Yeah,” he mumbles. He doesn’t say anything else, and I feel panic setting in, he obviously doesn’t like small talk. I’m scared he’ll disappear again if I don’t think of something interesting to say, quickly.

“What’s your name?” I ask. I can’t believe I have the courage.

With a serious expression, he mumbles something that sounds like “KGB,” and I get nervous, because that’s the sort of thing that puts you on your guard. But when I ask again, I hear him sigh “Åge B.,” and I would sigh too if I was stuck with that name. I don’t have the courage to ask what the “B” stands for, in case it’s something embarrassing, and so I just nod encouragingly.

“That’s a good name for a man,” I say.

I’m disappointed that he doesn’t ask me what my name is, or what my favorite color is, or which cassette tape I’d take with me to a desert island if I could choose only one. It’s so wonderful to talk, I want to talk to Åge B. about everything I talked to Epsilon about. When Epsilon came home from work, I’d ask him how his day had been and what he’d done, and he’d say his day was good and he hadn’t done much. I thanked him for this window into his world. Then he’d ask me how my day was and what I’d done, and I’d tell him some story, like about how I think I saw a baby snake shedding its skin on the bathroom floor, but instead it was just a dust bunny. “Don’t you ever get the urge to talk to someone other than me?” Epsilon would ask every now and then. “But I’ve done that,” I’d say. “Don’t you remember the time I went with you to the Christmas party?”

“Well then,” Åge B. says.

“Well then,” I say and hurry off before he does.

I walk down toward the church and feel fat. Especially around the thighs. I hear that’s a normal reaction when you get rejected by someone of the opposite sex.

One time I really was fat, it was right after Stein died. I’d stopped walking to the lake, but I hadn’t stopped baking meringue, in fact I baked it even more often, and at first I thought that’s why my dress was getting tight around the waist. “Don’t you think I’m getting a little soft?” I asked Epsilon. But Epsilon didn’t want to hurt my feelings and said that on the contrary I was looking quite stiff.

“ ‘Aunt Flow’ hasn’t visited for a while,” I said to Epsilon, I couldn’t wait any longer. “She should’ve been here at least three times now.” I usually said “Aunt Flow,” so Epsilon wouldn’t get embarrassed, and now he took my hands in his. “But does this mean.?” he asked. “I think it means more than we can imagine,” I said. I looked at Epsilon and thought this is what true happiness looks like. Even though I’d become immune to the tears in his eyes — I’d seen them often enough — this time they were contagious.

Epsilon went with me to buy a new dress. I had to wear the new one home, since I’d taken the old one off in the dressing room and couldn’t get it back on again. I needed something to grow into, so I bought a dress that was so huge I could wear it over my coat. “But is that really necessary?” Epsilon asked. “No,” I said. “But it can’t hurt.” Even though I was walking right beside him, he looked anywhere but at me, like he was trying to figure out where I’d gone. It was probably because the white dress blended with the snow in the gutters. I asked him to pull down the scarf he’d drawn up to his nose, because it hid the lower half of his face. “People will think you’re doing drugs.”

For the first time, Epsilon didn’t ask if I wanted to go with him to the Christmas party. He just put the invitation on the desk and assumed he’d be going alone. So I told him I wanted to come with him. If anyone asked me a question, I could just pat my belly and that would be answer enough. Plus, no matter how awful the experience was, I wouldn’t be facing it alone. Now I was a two-for-one. Epsilon called me brave, and I got a sudden whim and knitted a long red belt, which I tied in a huge bow around my waist, red on white. When we arrived at the Statistics Office cafeteria though, I was feeling much less brave, especially when I realized I wouldn’t be sitting beside Epsilon at all. “Mrs. Martinsen” read a name card at the other end of the horseshoe-shaped table. Before I could tell him I’d changed my mind and that this was a bad idea, Epsilon was already on the way to his seat. I nervously adjusted my bow and sat down. The chair to my right was empty. On my left was “Mr. Dahl.” Luckily, he was drunk. However, he snuffled so much I had no idea what he was saying; in fact, he was only saying one word over and over. I guessed: “Eskimo?” Dahl shook his head and, struggling not to fall out of his seat, said the word again. “Genghis Khan?” I asked. The whole time I was watching Epsilon, wanting him to see what a social butterfly his wife was. Dinner came and went. But then, three more tries: “Geronimo?” I asked at last. “Geronimo!” said Dahl. We were both relieved. However, neither of us had anything to add, and during dessert we just sat there and nodded.

I could see that Epsilon was keyed up, and I could tell that the woman at his table was quite the extrovert. She laughed at something he said, and when she got up from the table and headed for the bathroom, I followed her. I wanted to tell her that Epsilon wasn’t funny at all, even though I knew I’d never be brave enough to say it. However, at least I could make sure she saw my stomach. I acted like I was washing my hands when she came staggering out of the stall. She came up beside me and studied herself in the mirror. She was wearing a simple black dress. I wadded my red belt into a bundle. She began drawing her fingers through her hair, which hung over her shoulders, and said she really should comb it. I didn’t know who she was talking to because there was no one else there. I tied the red belt on again. “You have long hair,” I said, more to myself than to her. “It’s not long enough,” she said. Then she closed her eyes, I didn’t know why. I thought maybe she was trying to imagine something as she stood there swaying. That made me uncomfortable, because now I was forced to try and imagine what she was imagining, which was her, covered only by her long hair. Then I remembered that her hair wasn’t long enough. I left the bathroom before she could open her eyes. Since I felt talked out, I found Epsilon and said I was ready to go. But he said he’d promised the woman at his table a dance. “You’re not a funny man,” I wanted to say. But then he thoughtfully asked if I was feeling okay, so I told him that on a scale of one to three , things were fine with me. That rhymed, even though I didn’t mean it.

I stood against the wall and watched them. It was hard to stay still. What I really wanted to do was march up to him and say: “I’m putting my foot down, Epsilon.” I crossed my arms over my stomach, then dropped them to my sides, and finally I performed a few dance steps. I didn’t know what to do with myself. Epsilon looked like a different person. Funnier, now that I thought about it, but in a good way. The hair on the back of his head stuck out just like his ears; the woman’s hand nested on the back of his neck. Finally, I calmed down, because I realized that I was only jealous of myself: after all, I was the one who was actually with him. I even loved him.

Читать дальше