All was quiet on the riverbank except for the river’s throaty whisper. No one was screaming for his mother, and it was then I knew that the darker marine was also dead. I turned to Bon and in the lunar light I saw the whites of his eyes as he looked at me, wet with the sheen of tears. If it wasn’t for you, you stupid bastard, Bon said, I’d die here. He was crying for only the third time since I had known him, not in that apocalyptic rage as when his wife and son died, or in the sorrowful mood that he shared with Lana, but quietly, in defeat. The mission was over, he was alive, and my plot had worked, no matter how clumsily or inadvertently. I had succeeded in saving him, but only, as it turned out, from death.

Only from death? The commandant appeared genuinely wounded, his finger resting on the last words of my confession. In his other hand was a blue pencil, the color chosen because Stalin had also used a blue pencil, or so he told me. Like Stalin, the commandant was a diligent editor, always ready to note my many errata and digressions and always urging me to delete, excise, reword, or add. Implying that life in my camp is worse than death is a little histrionic, don’t you think? The commandant seemed eminently reasonable as he sat in his bamboo chair, and for a moment, sitting in my bamboo chair, I, too, felt that he was eminently reasonable. But then I remembered that only an hour earlier I had been sitting in the windowless, redbrick isolation cell where I had spent the last year since the ambush, rewriting the many versions of my confession, the latest of which the commandant now possessed. Perhaps your perspective differs from mine, Comrade Commandant, I said, trying to get used to the sound of my own voice. I had not spoken to anyone in a week. I’m a prisoner, I went on, and you’re the one in charge. It may be hard for you to sympathize with me, and vice versa.

The commandant sighed and laid the final sheet of my confession on top of the 294 other pages that preceded it, stacked on a table by his chair. How many times must I tell you? You’re not a prisoner! Those men are prisoners, he said, pointing out the window to the barracks that housed a thousand inmates, including my fellow survivors, the Lao farmer, the Hmong scout, the philosophical medic, the darkest marine, the dark marine, and Bon. You are a special case. He lit a cigarette. You are a guest of myself and the commissar.

Guests can leave, Comrade Commandant. I paused to observe his reaction. I wanted one of his cigarettes, which I would not get if I angered him. Today, however, he was in a rare good mood and did not frown. He had the high cheekbones and delicate features of an opera singer, and even ten years of warfare fought from a cave in Laos had not ruined his classically good looks. What rendered him unattractive at times was his moroseness, a perpetual, damp affliction he shared with everyone else in the camp, including myself. This was the sadness felt by homesick soldiers and prisoners, a sweating that never ceased, absorbed into a perpetually damp clothing that could never be dried, just as I was not dry sitting in my bamboo chair. The commandant at least had the benefit of an electric fan blowing on him, one of only two in the camp. According to my baby-faced guard, the other fan was in the commissar’s quarters.

Perhaps a better term than “guest” is “patient,” the commandant said, editing once more. You have traveled to strange lands and been exposed to some dangerous ideas. It wouldn’t do to bring infectious ideas into a country unused to them. Think of the people, insulated for so long from foreign ideas. Exposure could lead to a real catastrophe for minds that aren’t ready for them. If you saw the situation from our point of view, you would see that it was necessary to quarantine you until we could cure you, even if it hurts us to see a revolutionary like yourself kept in such conditions.

I could see his point of view, albeit with some difficulty. There were reasons to be suspicious of someone like me, who had endured suspicion all his life. But still, it was hard for me not to feel that a year in an isolation cell from which I was allowed to emerge only an hour a day for exercise, blinking and white, was unwarranted, as I had informed him at each of these weekly sessions where he criticized my confession and I, in turn, criticized myself. These reminders I had given him must also have been on his mind, because when I opened my mouth to speak again, he said, I know what you’re going to say. As I told you all along, when your confession reaches a satisfactory state, based on our reading of it and on my reports of these self-criticism sessions to the commissar, you will move on to the next and, we hope, last stage of your reeducation. In short, the commissar believes you ready to be cured.

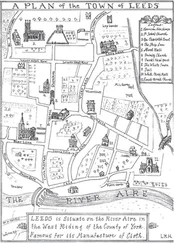

He does? I had yet to even meet the faceless man, otherwise known as the commissar. None of the prisoners had. They saw him only during his weekly lectures, sitting behind a table on the dais of the meeting hall where all the prisoners gathered for political lectures. I had not even seen him there, for these lectures, according to the commandant, amounted only to an elementary school education designed for pure reactionaries, puppets brainwashed by decades of ideological saturation. The faceless man had decreed me exempt from these simple lessons. Instead, I was privileged by having no burdens except to write and to reflect. My only glimpses of the commissar had come on those rare moments when I looked up from my exercise pen and saw him on the balcony of his bamboo quarters, atop the larger of the two hills overlooking the camp. At the base of the hills clustered the kitchen, mess hall, armory, latrines, and warehouses of the guards, along with the solitary rooms for special cases like me. Barbed-wire fencing separated this interior camp of the guards from the exterior camp where the inmates slowly eroded, the former soldiers, security officers, or bureaucrats of the defeated regime. Next to one of the gates in this fencing, on the interior side, was a pavilion for family visits. The prisoners had become emotional cacti in order to survive, but their wives and children inevitably wept at the sight of their husbands and fathers, whom they saw, at most, a couple of times a year, the trek from even the nearest city an arduous one involving train, bus, and motorbike. Beyond the pavilion, the exterior camp itself was fenced off from the wasteland of barren plains surrounding us, the fence demarcated with watchtowers where pith-helmeted guards with binoculars could observe female visitors and, according to the prisoners, entertain themselves. From the elevated height of the commandant’s patio, one could see not only these voyeurs but also the cratered plains and denuded trees surrounding the camp, a forest of toothpicks over which gusts of crows and torrents of bats soared in ominous black formations. I always paused on the patio before entering his quarters, savoring for a moment the view denied to me in my isolation cell, where, if I had not yet been cured, I had certainly been baked by the tropical sun.

You have complained often about the duration of your visit, the commandant said. But your confession is the necessary prelude to the cure. It is not my fault that it took you a year to write this confession, one that is not, in my opinion, even very good. Everyone except you has confessed to being a puppet soldier, an imperialist lackey, a brainwashed stooge, a colonized comprador, or a treacherous henchman. Regardless of what you think of my intellectual capacities, I know they’re just telling me what I want to hear. You, on the other hand, won’t tell me what I want to hear. Does that make you very smart or very stupid?

I was still somewhat dazed, the bamboo floor wobbling under my bamboo seat. It always took me at least an hour to become readjusted to light and space after my cell’s cramped darkness. Well, I said, gathering the tattered coat of my wits about me, I believe the unexamined life is not worth living. So thank you, Comrade Commandant, for giving me the opportunity to examine my life. He nodded approvingly. No one else has the luxury I have of simply writing and living the life of the mind, I said. My orphaned voice, which had detached itself in my cell and spoken to me from a cobwebbed corner, had returned. I am smart in some ways, stupid in others. For example, I am smart enough to take your criticism and editorial suggestions seriously, but I am too stupid to understand how my confession has not met your high standards, despite my many drafts.

Читать дальше