Nothing was more clear-cut than civilization versus barbarism, but what was the killing of the crapulent major? A simple act of barbarism or a complex one that advanced revolutionary civilization? It had to be the latter, a contradictory act that suited our age. We Marxists believe that capitalism generates contradictions and will fall apart from them, but only if men take action. But it was not just capitalism that was contradictory. As Hegel said, tragedy was not the conflict between right and wrong but right and right, a dilemma none of us who wanted to participate in history could escape. The major had the right to live, but I was right to kill him. Wasn’t I? When Claude and I left near midnight, I came as close as I could to broaching the subject of my conscience with him. As we smoked farewell cigarettes on the sidewalk, I asked the question that I imagined my mother asking of me: What if he’s innocent?

He blew a smoke ring, just to show he could. No one’s innocent. Especially in this business. You don’t think he might have some blood on his hands? He identified Viet Cong sympathizers. He might have gotten the wrong man. It’s happened before. Or if he himself is a sympathizer, then he definitely identified the wrong people. On purpose.

I don’t know any of that for sure.

Innocence and guilt. These are cosmic issues. We’re all innocent on one level and guilty on another. Isn’t that what Original Sin is all about?

True enough, I said. I let him go with a handshake. The airing of moral doubts was as tiresome as the airing of domestic squabbles, no one really interested except for the ones directly involved. In this situation, I was clearly the only one involved, except for the crapulent major, and no one cared to hear his opinion. Claude, meanwhile, had offered me absolution, or at least an excuse, but I did not have the heart to tell him I could not use it. Original Sin was simply too unoriginal for someone like me, born from a father who spoke of it at every Mass.

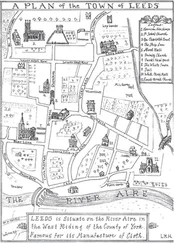

The next evening I began reconnoitering the major. On that Sunday and the following five, from May until the end of June, I parked my car half a block from the gas station, waiting for eight o’clock when the crapulent major would leave, walking slowly home, lunch box in hand. When I saw him turn the corner, I started the car and drove it to the corner, where I waited and watched him walk down the first block. He lived three blocks away, a distance a thin, healthy man could walk briskly in five minutes. It took the crapulent major approximately eleven, with myself always at least a block behind. During six Sundays, he never varied his routine, faithful as a migratory mallard, his route taking him through a neighborhood of apartments that all seemed to be dying of boredom. The major’s own diminutive quadriplex was fronted by a carport with four slots, one vacant and three occupied by cars with the dented, drooping posteriors of elderly bus drivers. An overhanging second floor, its two sets of windows looking onto the street, shaded the cars. At 8:11 in the evening or so, the morose eyes of those bedroom windows were open but curtained, only one of them lit. On the first two Sundays, I parked at the corner and watched as he turned into the carport and vanished. On the third and fourth Sundays, I did not follow him from the gas station but waited for him half a block past his apartment. From there, I watched in my mirror as he entered the carport’s shadowed margin, a lane leading to the bottom apartments. As soon as he disappeared those first four Sundays, I went home, but on the fifth and sixth Sundays I waited. Not until ten o’clock did the car that parked in the vacant spot appear, as aged and dinged as the others, the driver a tired-looking Chinese man wearing a smeared chef’s smock and carrying a greasy paper bag.

On the Saturday before our appointment with the crapulent major, Bon and I drove to Chinatown. In an alley off Broadway lined with vendors selling wares from folding tables, we bought UCLA sweatshirts and baseball caps at prices that guaranteed they were not official merchandise. After a lunch of barbecued pork and noodles, we browsed one of the curio shops where all manner of Orientalia was sold, primarily to the non-Oriental. Chinese chess sets, wooden chopsticks, paper lanterns, soapstone Buddhas, miniature water fountains, elephant tusks with elaborate carvings of pastoral scenes, reproductions of Ming vases, coasters with images of the Forbidden City, rubber nunchaku bundled with posters of Bruce Lee, scrolls with watercolor paintings of cloud-draped mountain forests, tins of tea and ginseng, and, neither last nor least, red firecrackers. I bought two packets and, before we returned home, a mesh sack of oranges from a local market, their navels protruding indecently.

Later that evening, after dark, Bon and I ventured out one more time, each of us with a screwdriver. We toured the neighborhood until we reached an apartment with a carport like the crapulent major’s, the cars not visible from any neighboring windows. It took less than thirty seconds for Bon to remove the front license plate from one car, and myself the plate from the rear. Then we went home and watched television until bedtime. Bon fell asleep immediately, but I could not. Our visit to Chinatown reminded me of an incident that had taken place in Cholon years before with the crapulent major and myself. The occasion was the arrest of a Viet Cong suspect who had graduated from the top of our gray list to the bottom of our blacklist. Enough people had fingered this person as a Viet Cong for us to neutralize him, or so the major said, showing me the thick dossier he had compiled. Official occupation: rice wine merchant. Black market occupation: casino operator. Hobby: Viet Cong tax collector. We cordoned off the ward with roadblocks on all streets and foot patrols in the alleys. While the secondary units did ID checks in the neighborhood, fishing for draft dodgers, the major’s men entered the rice wine merchant’s shop, pushed past his wife to reach the storeroom, and found the lever that opened a secret door. Gamblers were shooting craps and playing cards, their rice wine and hot soup served for free by waitresses in outrageous outfits. On seeing our policemen charging through the door, all the players and employees promptly dashed for the rear exit, only to find another squad of heavies waiting outside. The usual high jinks and hilarity ensued, involving much screaming, shrieking, billy clubs, and handcuffs, until, at last, it was only the crapulent major, myself, and our suspect, whom I was surprised to see. I had tipped off Man about the raid and fully expected the tax collector to be absent.

VC? the man cried, waving his hands in the air. No way! I’m a businessman!

A very good one, too, the major said, hefting a garbage bag filled with the casino’s cash.

So you got me there, the man said, miserable. He had an overbite and three long, lucky hairs sprouting from a mole the size of a marble on his cheek. Okay, take the money, it’s yours. I’m happy to contribute to the cause of the police.

That’s offensive, the major said, poking the man’s gut with his billy club. This is going to the government to pay your fines and back taxes, not to us. Right, Captain?

Right, I said, the straight man in this routine.

But as to future taxes, that’s a different matter. Right, Captain?

Right. There was nothing I could do for the tax collector. He spent a week in the interrogation center being beaten black and blue, as well as red and yellow. By the end, our men were convinced that he was not a VC operative. The proof was incontrovertible, arriving in the form of a sizable bribe the man’s wife brought to the crapulent major. I guess I was mistaken, he said cheerfully, handing me an envelope with my share. It was equivalent to a year’s salary, which, to put it into perspective, was actually not enough to live on for a year. Refusing the money would have aroused suspicion, so I took it. I was tempted to use it for charitable activity, namely the support of beautiful young women hampered by poverty, but I remembered what my father said, rather than what he did, as well as Ho Chi Minh’s adages. Both Jesus and Uncle Ho were clear that money was corrupting, from the moneylenders desecrating the temple to the capitalists exploiting the colony, not to mention Judas and his thirty pieces of silver. So I paid for the major’s sin by donating the money to the revolution, handing it to Man at the basilica. See what we’re fighting against? he said. Holy Mary, mother of God, pray for us sinners, droned the dowagers. This is why we’ll win, Man said. Our enemies are corrupt. We are not. The point of writing this is that the crapulent major was as sinful as Claude estimated. Perhaps he had even done worse than simply extort money, although if he did it did not make him above average in corruption. It just made him average.

Читать дальше