Changing our country

More often than our shoes,

Through the class war.

Unbeknownst to Lin, this was a poem by Brecht. The policeman told him it was a poem by a German poet who supported the Comintern, and that he had just translated it into English.

The car took him to a shih-k’u-men house on Rue Wantz. Lin immediately recognized the man standing beneath the ceiling fan in the living room. “Secretary Ch’en!” Many years ago, Lin had sat in the audience when Ch’en had been speaking on the podium as the leader of the Student Communists.

Several hours later, as he was leaving the house, he had to make himself calm down and not get too worked up. His world had been turned upside down. This is a conspiracy, a threat to the Party! If Ku pulls this off, it will be a blow to the Revolution. We must expose and defeat him — this is the mission with which the Party is entrusting you.

Four whole years, he had spent four years under the leadership of a mere charlatan whom he had taken to be a representative of the Party, his only connection to the Party, his mentor. He had lost touch with the Party after the massacres in the spring of 1927. All his comrades were arrested or had dropped out of the Party, and the most important person in his life — not that he had ever had a chance to express his feelings to her — was killed by a blow to the head by a Green Gang thug wielding a baton. When he returned to Shanghai from Wuxi in November of 1927, Year 16 of the Republic, his friends’ revolutionary fervor had died down. In March, a classmate from his hometown had come to see him, and spent half an hour talking about the struggle against imperialism and the warlords before saying: my uncle used to be a teacher in Wuxi, but he’s unemployed. You couldn’t get him a job somewhere, could you? With your position as a Communist on the Kuomintang’s Student District Committee? At the time, all schools were governed by a Kuomintang department consisting of representatives from both parties.

But now that classmate ignored Lin and pretended not to know him when they ran into each other on the street. Lin had thought of going to Wuhan to meet up with Party members there, but the persecution of Communists soon spread to Wuhan. He was not angry at the enemy. No, he hated the enemy — he was angry at all his former comrades who had betrayed the cause.

That was when he had met Ku Fu-kuang. He had been coming out of a lonely bookstore which, only months ago, had been full of socialist books and magazines in several languages. The Shanghai Kuomintang hadn’t yet been able to shut it down because it was in the International Settlement, and the owner was a German. At the time, he could tell that he was in danger, though in retrospect he could see that the true danger was not what he had feared. Someone was looking at him. He went into the longtang, and as he turned the corner, he glanced over and met the gaze of two men looking at him. Tensing up, he walked faster, and he thought he could hear footsteps behind him. Ku was hiding in the alley. He said in a low voice: “This way!” Lin followed him into a shih-k’u-men house, through the courtyard, and out another door.

Now that he thought about it, after hearing Comrade Cheng’s anecdote, he realized that the entire incident could have been a crude trap.

He was ashamed of having been so gullible. He had fallen for it because he had been full of hatred, anxious to exact revenge on the counterrevolutionaries. But his enemy was the system, the class, and hatred is a dangerous emotion for a revolutionary. He had to outdo the enemy in staying power. Just thinking about Secretary Ch’en’s words filled him with shame.

When Lin requested formal readmission to the Party, Secretary Ch’en told him that the Party had learned its lesson from the violence of the oppression. Its ranks had to be more disciplined, and Party members would have stricter requirements to fulfill. That meant that procedures for rejoining the Party would also be tightened. Most importantly, Lin had a mission to complete and no time to lose. He had to tell the truth to his comrades who had been duped by Ku, and tell them that the Party would welcome their return.

Lin stood at the window and waved at the man in the teahouse on the other side of the road, who was carrying a classified document that would explain the Party’s latest strategy to his misled comrades. But first he had to talk to them all and expose Ku’s fraudulent schemes.

He looked at Hsueh, who was fast asleep on the bed. There was one more thing he had to know: what happened at North Gate Police Station. When Secretary Ch’en had asked him about Hsueh, Lin had been amazed that the Party seemed to know everything about everything. Their mole in the Political Section said that Hsueh had an unusual position there because of his ties to Inspector Maron’s new detective squad. The Party had arranged for a sum of money to be deposited in an account at the National Industrial Bank, and earmarked for dealing with corrupt policemen in the Concession. Party leaders were taking an interest in the new detective squad. Another undercover comrade, a clerk at the National Industrial Bank counter on Rue du Consulat, discovered by chance that this Hsueh had withdrawn some money from the account. The Party investigated Hsueh, and decided that he was not a counterrevolutionary. He had rescued Leng because of their relationship, and Leng’s deceitfulness didn’t mean that she had betrayed the Party or gone over to the police’s side.

Lin had Ch’in wake Hsueh up for dinner. As he was serving Hsueh a piece of smoked fish, Lin asked: “So what happened this morning at the Astor? And tell us about the delivery last night. What is the mysterious weapon?”

“How is she? Therese?”

“We don’t know yet. Our man stationed at the scene says she was rushed to Shanghai General Hospital by hotel staff. You have to tell us everything. Ku might well be sending someone to the hospital to kill her.”

“I don’t know anything. You should talk to Leng.”

JULY 13, YEAR 20 OF THE REPUBLIC.

11:55 P.M.

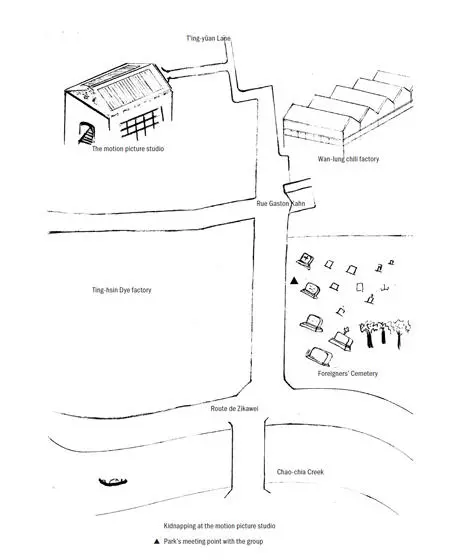

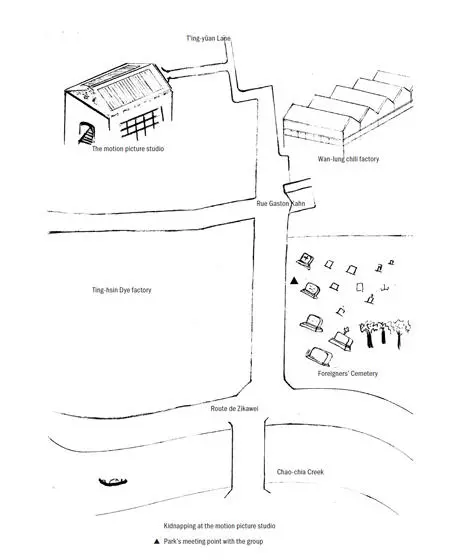

Park sat on the concrete with his back to the gravestone. It was the grave of a Jesuit who had come to Shanghai at the end of the Ching Dynasty, in the Foreigners’ Cemetery on Rue Gaston Kahn, and it was oval shaped, a meter deep in the ground, and made of concrete. A south wind from Chao-chia Creek carried the stench of boatloads of night soil toward them. The stench only grew worse when the wind died down. Ting-hsin Dye Factory lay across the road on Rue Gaston Kahn, and a chili factory lay to the north.

They all arrived separately within five minutes of each other, so as not to attract police attention. Park looked at his watch. He turned to Fu and said, “It’s time.” Then he led them out of the cemetery through a gap in the wall.

The moon hung low in the sky, the summer night was crowded with stars, and the sky was dream bright. An occasional splash of oars came from the direction of the wooden bridge to the south, so faint that it could have been a rat paddling in the water. There were no trees or streetlights on Rue Gaston Kahn. The road was short, and as they walked north, the tarmac road narrowed into a longtang paved with concrete. They turned into T’ing-yüan Lane. The Hua Sisters Motion Picture Studio was at the end of the lane.

Читать дальше