“Did you hurt your leg playing sports?”

“Stepped in a gopher hole. A stupid thing to do. I wasn’t looking. Now, I always look. Of course I’m speaking metaphorically. Whatever that means.”

We found our way to the dining hall in the student center. We grabbed trays and collected food. I picked up a burger and fries while Everett filled a bowl with salad and another with cottage cheese. As we stood in line, he looked at my tray and his. “Can you believe they have us pay for this shit?”

“It looks okay,” I said.

He nodded. “Maybe.”

We sat at a round table by the wall of windows and looked out at the passersby. He held a cherry tomato on the tines of his fork and then looked at me. “Are you a sheep, Mr. Poitier?”

“No,” I said. “I don’t think so.”

“Most sheep don’t think they’re sheep. I wonder what they think they are. Pigeons, maybe.”

I ate a fry and looked out at the guys walking along.

“So, what makes you interested in my class?” he asked.

“Nonsense,” I said, flatly.

“Good.” He laughed. “Keep it that way. You do your part and I’ll do my part and all will be right in Mudville. Or Atlanta. Or maybe even Jonestown.”

“What will the class be like?” I asked.

“Who knows?” he said. “We’ll learn something, maybe. We’ll read some stuff, maybe a lot of stuff. What, I don’t know yet. You guys will do some presentations, I suppose. Bore each other and, sadly, me to sleep. Probably be some papers to write. Not long papers. I couldn’t take that. I’m not a detail person.” He finally ate the tomato from the end of his fork. “Are you living on campus?”

The question caught me off guard. For some reason it had never occurred to me that I might live at school. “I haven’t decided,” I said.

He didn’t pause. With his glass to his lips, he said, “Might want to make a decision on that one. The dorms fill up fast, I’m told. Don’t ask me why. They look like prisons.”

“Do you think it’s a good idea?”

He shrugged. “There’s a lot of frat idiocy on this campus.” He looked at me and seemed to consider his words. “You might like it, though. Who knows? You should talk to other people about it. I’m not the person to ask. Where are you living now?” Before I could answer, “Don’t tell me. I’m really not interested. Besides, it’s a good rule to never trust anyone who tells you all their business right away. Mind if I have a couple of your fries?”

I gestured that it was okay.

He popped one into his mouth. “Been over to Spelman yet?”

“No.”

“What the hell is wrong with you? That’s why men come to Morehouse. The only good reason.”

“I thought it was because of the storied history,” I said, using a phrase I’d read in some brochure.

“Well, there’s that. Whatever that is. What doesn’t have a storied history?” Everett ate another couple of fries. “Well, I’ll see you in class, Mr. Poitier.”

But he didn’t get up. It became clear that he expected me to leave. He pulled out a cigar as I collected my tray.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “I won’t light it in here. They’ll all have a fit. I usually don’t light them at all anymore. I read a book about U.S. Grant, and he had tongue cancer from these things. He felt as if he were swallowing razor blades at the end. I’ve never swallowed a razor blade, but I imagine it’s awful.”

“See ya,” I said.

“Don’t be a sheep, Mr. Poitier. Be anything, be a deer or a squirrel, a beaver or a gnu, but don’t be a sheep.”

“Okay.”

“Be a gecko or a platypus. Be a panther or a sparrow, but not a sheep. Promise me that.”

“Okay.”

I walked away and out of the building. People moved by me like animals and in fact they were, as am I, but they seemed so far away. Or at least I did: I felt like a study by Muybridge. Occasionally I sensed the gaze of someone on me, as if I were being watched, and I imagined them wondering, as I walked too quickly, whether my feet were ever off the ground at the same time, like a horse trotting.

A strategically placed phone call to Gladys Feet and the promise of a few more dollars got me a room in Brazeal Hall and a roommate. It also got me a clearer sense that Gladys Feet was flirting with me.

“Perhaps we could have lunch again,” she said.

“I don’t know why that would be necessary.”

“I thought you might give me a sense of how you’re adjusting to campus life. I’d love to hear how you think we might improve things.” In a softer, slightly deeper voice, she said, “We could meet well off campus.”

“No, thank you.” I hung up.

My roommate was the kind of guy who was considered cool on campus. In other words, my opposite. And he was none too happy to see me show up, as he believed that he would be living in the moderately tight space all alone. His name was Morris Chesney, and it’s fair to say that he hated me from the moment he laid eyes on me. He was not quite as tall as me and this stuck in his craw. He had loose curly hair that he loved to run his fingers through, all the time. His eyes were green, and, from his generously offered reports at least, the Spelman girls loved them. When I arrived with my one bag, Morris had to abandon a closet; however, it was clear that all of his stuff would not fit into one, so I suggested, like a simp, that he take some space in mine.

I said, “Really, Morris, I don’t have many things. You’re welcome to use this side of my closet.” I made the gesture in the spirit of getting along, being college buddies, elementary generosity. And so he proceeded to store his dirty gym shorts and sweat socks in there. To have called Morris Chesney passive-aggressive would have been a glaring understatement, as much as any understatement can glare. To have called him an egotistical, self-centered, not-terribly-bright asshole with a mean streak a mile wide would have been fairly accurate.

The room was what one might expect, essentially a cell. On the walls that were a color I called cholera were posters of musical groups the names of which I had heard in high school only in passing. Lots of guys in silky white suits who looked as cool as Morris Chesney — all either running their fingers through their hair or looking like they had just done so, and scantily covered curvy women in impossible, though not altogether uninteresting, poses.

Morris laughed when I told him my name. “What kind of stupid-ass name is Not?” he said.

“My name is Not Sidney.”

“Excuse me, Not Sidney. I’ll say you’re not Sidney.”

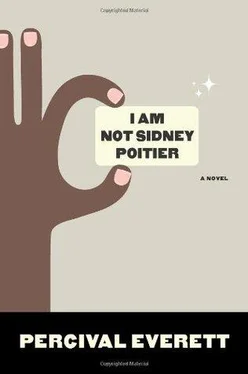

What was meant as an insult would have been a glancing blow at best, if I had cared. But what Morris Chesney had done was articulate what no one else ever had. He had said what probably everyone else meant to say but couldn’t come up with, or wouldn’t. He had pointed out to me that not only was I Not Sidney Poitier, but also that I was not Sidney Poitier: a confusing but profound and ultimately befuddling distinction, one that might have been formative or at least instructive for a smarter person.

Still, I responded to his intended insult with, “But you are every bit Morris Chesney.”

This stung him though he had no idea what I meant, and he really couldn’t have because I didn’t know what I meant, however much I believed it. This started an application of what would become a familiar, though not unwelcome, silent treatment that lasted two whole days.

Not surprisingly, which is the understater’s way of saying of course, Morris Chesney’s friends saw fit to dislike me as much as he did. From the first day, they would litter the room with themselves and trash and stare at me. Sitting there in a clump like that they reminded me of the bullies that used to beat me up on the playgrounds when I was growing up, but now I was unafraid, perhaps a foolish condition in any situation. One asked me what my major was and I said I didn’t know. Then they all laughed. Then he asked how I came to be in an upperclassmen’s dorm and I offered a lie, said the others were full. The answer seemed in some way to satisfy them, but did not make them happy.

Читать дальше