‘I thought Tom Russell spoke well,’ said Fletcher, ‘and more important, he represents their views.’

‘No, he won’t do any more than keep the seat warm for you.’

‘Don’t be too sure of that,’ said Fletcher. ‘Tom might quite like the idea of becoming president.’

‘Not a chance with what I have planned for him.’

‘Dare I ask what you have in mind?’ said Fletcher.

‘I had a member of our team present whenever he gave a speech. During the campaign he made forty-three pledges, most of which he will not be able to keep. After he’s been reminded of that fact twenty times a day, I don’t think his name will be appearing on the ballot paper for president.’

‘Jimmy, have you ever read Machiavelli’s The Prince ?’ asked Fletcher.

‘No, should I?’

‘No, don’t bother, he has nothing to teach you. What are you doing for dinner tonight?’ he added, as Annie came across to join them. She gave Fletcher a big hug. ‘Well done,’ she said, ‘your speech was brilliant.’

‘Too bad a couple of hundred others didn’t agree with you,’ said Fletcher.

‘They did, but most of them had decided how they were going to vote long before they entered the hall.’

‘That’s exactly what I’ve been trying to tell him.’ Jimmy turned to Fletcher. ‘My kid sister’s right, and what’s more...’

‘Jimmy, I’ll be eighteen in a few weeks’ time,’ said Annie, scowling at her brother, ‘just in case you haven’t noticed.’

‘I’ve noticed, and some of my friends even tell me that you’re passably pretty, but I can’t see it myself.’

Fletcher laughed. ‘So are you going to join us at Dino’s?’

‘No, you’ve obviously forgotten that Joanna and I invited you both to dinner at her place.’

‘I hadn’t forgotten,’ said Annie, ‘and I can’t wait to meet the woman who’s tied my brother down for more than a week.’

‘I haven’t looked at another woman since the day I met her,’ said Jimmy quietly.

‘But I still want to marry you,’ said Nat, holding on to her.

‘Even if you can’t be sure who the father is?’

‘That’s all the more reason for us to get married, then you’ll never doubt my commitment.’

‘I’ve never doubted it for a moment,’ said Rebecca. ‘or that you’re a good and decent man, but haven’t you considered the possibility that I might not love you enough to want to spend the rest of my life with you?’ Nat let go of her and looked into her eyes. ‘I asked Ralph what he would do if it turned out to be his child, and he agreed with me that I should have an abortion.’ Rebecca placed the palm of her hand on Nat’s cheek. ‘Not many of us are good enough to live with Sebastian, and I’m certainly no Olivia.’ She took her hand away and quickly left the room without another word.

Nat lay on her bed unaware of the darkness setting in. He couldn’t stop thinking about his love for Rebecca, and of his loathing for Elliot. He eventually fell asleep, and woke only when the telephone rang.

Nat listened to the familiar voice and congratulated his old friend when he heard the news.

When Nat went to pick up his mail from the student union, he was pleased to find he had three letters: a bumper crop. One of them bore the unmistakable hand of his mother. The second was postmarked New Haven, so he assumed it had to be from Tom. The third was a buff envelope containing his monthly scholarship cheque, which he would bank immediately as his funds were running low.

He walked across to McConaughy and grabbed a bowl of cornflakes and a couple of slices of toast, avoiding the powdered scrambled eggs. He took a vacant seat in the far corner of the room, and tore open his mother’s letter. He felt guilty that he hadn’t written to her for at least two weeks. There were only a few days to go before the Christmas vacation, so he hoped she would understand if he didn’t reply immediately. He’d had a long conversation with her on the phone the day after he had broken up with Rebecca. He hadn’t mentioned her being pregnant or given a particular reason for them breaking up.

My dear Nathaniel — she never called him Nat. If anyone ever read a letter from his mother, Nat reckoned that they would quickly learn everything they needed to know about her. Neat, accurate, informative, caring but somehow leaving an impression of being late for her next appointment. She always ended with the words, Must dash, love Mother. The only piece of real news she had to impart was Dad’s promotion to regional manager, which meant he would no longer have to spend endless hours on the road, but in future would be working in Hartford.

Dad is delighted about the promotion and the pay rise, which means we can just about afford a second car. However, he’s already missing the personal contact with the customers.

Nat took another spoonful of cereal before he opened the letter from New Haven. Tom’s missive was typed and contained the occasional spelling mistake, probably caused by the excitement of describing his election victory. In his usual disarming way, Tom reported that he had won only because his opponent had made a passionate speech defending America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, which hadn’t helped his cause when it came to the ballot. Nat liked the sound of Fletcher Davenport, and realized that he might well have run up against him had he gone to Yale. He bit into his toast as he continued to read Tom’s letter: I was sorry to hear about your break-up with Rebecca. Is it irreconcilable? Nat looked up from the letter not sure of the answer to that question, although he realized his old friend wouldn’t be at all surprised once he discovered Ralph Elliot was involved.

Nat buttered a second piece of toast and for a moment considered whether a reconciliation was still possible, but quickly returned to the real world. After all, he still planned to go on to Yale just as soon as he’d completed his first year.

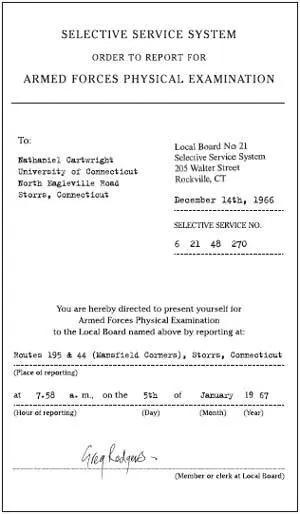

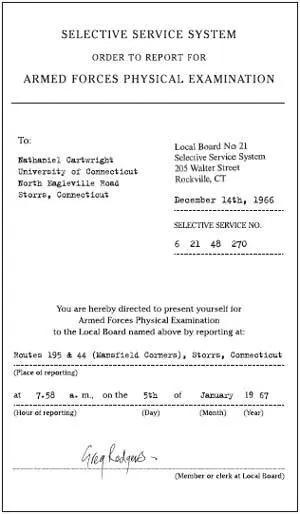

Finally Nat turned his attention to the brown envelope and decided he would drop his monthly cheque off at the bank before his first lecture — unlike some of his fellow students, he couldn’t afford to leave banking his meagre funds until the last moment. He slit open the envelope, and was surprised to find that there was no cheque enclosed, just a letter. He unfolded the single sheet of paper, and stared at the contents in disbelief.

Nat placed the letter on the table in front of him, and considered its consequences. He accepted that the draft was a lottery, and his number had come up. Was it morally right to apply for an exemption simply because he was a student, or should he, as his old man had done in 1942, sign up and serve his country? His father had spent two years in Europe with the Eightieth Division before returning home with the Purple Heart. Over twenty-five years later he felt just as strongly that America should be playing a role in Vietnam. Did such sentiments apply only to those uneducated Americans who were given little choice?

Nat immediately phoned home, and was not surprised when his parents had one of their rare disagreements on the subject. His mother was in no doubt that he should complete his degree, and then reconsider his position; the war could be over by then. Hadn’t President Johnson promised as much during the election campaign? His father, on the other hand, felt that though it might have been an unlucky break, it was nothing less than Nat’s duty to answer the call. If everyone decided to burn their draft card, a state of anarchy would prevail, was his father’s final word on the subject.

Читать дальше