Martin and Liesl Keller.

Berchtesgadener Hof Hotel

Berchtesgaden

Germany

29th June 1939

Dear Esmond –

I have left your father. I imagine you picked up on the coolness between us while you were there at Christmas, but since then things have deteriorated significantly and I felt I needed to make a Break for Freedom. I married your father for his courage and his conviction; in recent months he is short of both. I have been living too long in the shadow of a man I no longer respect. These must be hard things for you to hear, but I wanted to explain to you why I, too, have left England.

Ever since our first trip to National Socialist Germany, back in the bright days of the spring of ’35, I have felt strongly that the Führer had a vision of the future that would shape the Fate of the World. My visits with Mosley and Diana, and more recently on my own, have only confirmed this. We are moving into a Nazi Future and men like your father who try to resist this will be left behind.

I’m sure it must have seemed cruel to you, the burning of your books, your manuscript. I wanted to explain it to you at the time, but I knew your father would have thought it absurd. There is another Great War coming. Germany has been preparing since 1933, it will draw upon all the resources of Mitteleuropa, it has the kind of Deep Ideological Conviction its opponents lack. By the end of 1940, all Europe will be German, soon after, all of the globe will fly the Glorious Swastika. I burnt your degenerate books, your limp-wristed writing because I knew the risk they’d pose for you in the coming years. (I suggest you burn this letter, too.) We — the British Union, those of us who have remained faithful to the cause — will be at the forefront of Nazi Britain and we can’t have bad eggs amongst us. I hope you see that, Esmond.

Diana, Unity and I are in Berchtesgaden. I’m going to dinner at the Kelsteinhaus tonight. I can’t tell you how exciting this is. I feel like I’m breathing for the first time in my life, up here in the mountains. Don’t worry about your father — he has Anna to look after, his losing battle against the Tides of History to fight. I never really felt I knew my children, but I loved you. I hope you know that.

Heil Hitler!

Your Mother.

Telegram: 13/7/39

Many thanks for your generous wire STOP This has saved us from a most difficult time STOP We will repay you once these dark days are over STOP Martin and Liesl Keller

Royal Shrewsbury Infirmary,

Salop.

24/7/39

Darling E –

Everyone rather glum over mother leaving. Did she write to you? I can’t think she was terribly good to us, but I do miss her. Every evening now, daddy goes for mournful gallops across the countryside with the dogs. Not hunting, but still looking for something I think, in the copses, along the banks of the canal. He comes back covered in mud, looking provoked.

In the hospital, am on a new machine that does some of my breathing for me. Wonder when it’ll be that machines take over all our vital functions and we’re left sitting out infinity with only our various looks of unease to distinguish us. Sounds frightfully dull to me. Put myself in here by going for a long walk beside the canal two nights ago. It was damp and I wasn’t well-enough wrapped up but O the joy of it, striding along taking great lungfuls of air and watching clouds rush across the sky and feeling peppy for the first time in an age. Daddy doesn’t know how to talk to the nurses like mother did. He’s far too polite.

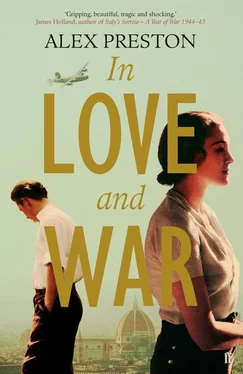

Sorry to hear Faber won’t take In Love and War. Bloody bastards. Don’t know a good thing when they see it. There are other publishers, you know — I do wish you’d send me a copy. I know you think it’s too filthy for my young eyes, but I promise I’d skip over the really grubby bits.

Daddy’s frightfully keen you should come home before the war starts. It would be super to have you, although I’ve no doubt he’d meet you off the train and march you straight down to the Knightsbridge barracks to enlist. Don’t go and get killed, darling. It would be too beastly of you.

Cough oodles cough,

Anna xxx.

Via dei Forbici, 35c

Firenze

12.8.39

Dear Esmond,

I am now going north — to Turin. It is said they are not implementing their vile laws with the same rigidity up there. Ettore Ovazza even claims he can find me work, perhaps. I will not flee to Switzerland just yet. Ada says she will stay here and I cannot persuade her otherwise. Look after her, perhaps bring some dinner over every now and again. She tends not to eat enough. I will write to her, and to you, often. I wish that she would come with me, but she says she belongs here, that she is a Florentine. It is with great sadness that I leave her, and this city.

With very best wishes and thanks,

Guido Liuzzi.

Welsh Frankton

Shropshire

26th August.

Dear Esmond,

I thought I’d sit down and write while our conversation was still fresh in my mind. It’s also an excuse to lock myself away in the library for an hour and not deal with the ghastly necessities of death — funeral invitations and readings and notes from well-wishers. The house is like a florist’s — bouquets on every table, pollen staining every carpet. Your mother has come back, of course, but she’s flying out again on the 30th. She’s frantic not to be trapped in England when the show starts. Odd to have her around the house again — we’d been rather getting used to life without her.

You were very brave on the telephone; I’m sorry I didn’t hold up my end quite so well. Anna loved you best of all, you know. You’re right that we should feel blessed to have had her in our lives as long as we did. I keep telling myself this in the hope it’ll comfort me. Not yet. So far it’s just a terrible sense that everything dear has reeled away from me. Your mother, Anna, the Party, the peaceful world I thought I was serving to build. Must be difficult to know that your father’s a failure, old chap, but the evidence is there for all to see.

Come home for the funeral, Esmond. Your brother needs you here. We all do. You don’t want to be scurrying over with every other Tom, Dick and Harriet when war’s declared — push off now, know that you’ve made a real contribution over the past few years and move on. I could get you into the Guards. Damned fine kit they have — you could do much worse. You’d be sure to see battle early on and that’s important with a war. Get out early and see a few bullets — you never know when it might all be over.

I’m afraid the Party’s more or less finished. Smashed on the rocks of history. I thought the Molotov — Ribbentrop Pact might turn a few within the Party my way, might make them see that the Nazis are the enemy every bit as much as the Reds. Joyce and Clarke and now, alas, Mosley and your mother have turned the British Union into Nazis, tout court. With the stories about what’s happening to the Jews in the work camps, the rounding up of innocent civilians, the stench of evil settling over Germany, they’ve simply hitched their cart to the wrong horse. Mosley is still making noises about peace, about the need to avoid another Ypres, another Somme, but our time is passing.

Wind things up and come back home, Esmond — it’s the right thing to do. It’s time for you to be the soldier you were meant to be. If not for me, do it for Anna.

I send you my love,

Your Father.

He stands with Ada on the Ponte Santa Trinità, his elbows on the parapet wall, crying into the water below. He feels himself unravelling with each breath, his spirit unstitching itself, dissolving into the yellow Arno. Ada has her hand on his shoulder. She is saying something, but he can’t understand her, can only see her lips move through the blur of his tears. He takes her in his arms and they stand there, and she feels bone-thin and so like Anna that he wonders for a moment if he will go mad. He wonders how much sorrow a mind can take — Anna, Philip, Fiamma — before it will no longer move through the world and sleeps in its own dark reaches.

Читать дальше