You shouldn’t let the success of your radio enterprise distract you from what I feel certain is your true calling — as novelist. I was fascinated by our discussion about T. E. Hulme, whose work I did not know. You are right that it is hard to find literary figures of the correct type — perhaps harder in England than in Italy. Here we have Ungaretti and Pirandello and, of course, the late d’Annunzio, whose passing we mourn each day and whose legacy (notwithstanding his regrettable assessment of the Axis alliance) I am now working to assure.

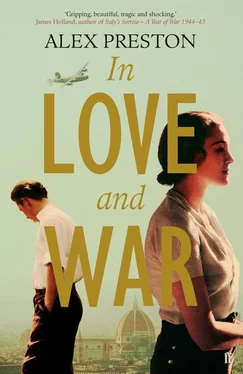

I like the idea of using the novel, with its mutability, its openness and its place at the heart of middle-class life, to address historical figures, situating them in moments of great political unease. Of course this is not new — your George Eliot famously treated the life of our own Savonarola; Manzoni’s The Betrothed is one of the great historical novels (have you read it? I enclose a copy in any case). But what seems new to me in your idea is to claim a figure from the very recent past and to use him to illuminate the current political landscape. I look forward very much to reading In Love and War when it is published.

As you can imagine, with d’Annunzio’s death, I have been terribly busy. I will try, nonetheless, to make it to Florence before the heat of the summer strikes and, if you will humour me, I would be delighted to continue my musings on the state of contemporary Italian literature.

With warmest wishes,

Alessandro.

Telegram: 1/4/38

Received with thanks four hundred pounds STOP Impressive STOP Mosley

Early morning. Esmond is sitting at his desk in the studio. He can still smell Ada’s lavender perfume. Voices rise up from the stalls on the Piazza Santo Spirito. The sound of a street sweeper’s broom is like the whetting of long knives. He sits in thought for a few moments, scratches his fountain pen across his notebook. He leans back, looks carefully at the last page, and gives a thin smile. He has finished his novel. With a sigh, he gathers together the pile of notebooks, puts a sheet of paper in his Olivetti, extends two fingers, and begins to type.

There is no such thing as historical fact. It is likely, however, that our hero, Thomas Ernest Hulme, twelve days after his thirty-fourth birthday, was standing in front of the Royal Marine Artillery battery at Oostduinkerke Bad, two hundred yards from the slate flushness of the North Sea. Witnesses — Captain Henry Halahan RN, for instance — say that Hulme appeared lost in contemplation as the shells descended. He’d just begun a book on Epstein, so it may have been this that caused his wood-cut features to smudge over, his ears to close themselves against the whistle of the falling shells, fired from the 15-inch Leugenboom at Ostend. His comrades threw themselves into the trenches, into the gun pit of the Carnac battery. Hulme just stood there, gazing over towards the long barges on the Yser Canal.

We know what the explosion sounded like, at least to Hulme. He’d had enough near-misses during his time in Flanders to know that, as he wrote to Ursula Lowndes, ‘It’s not the idea of being killed that’s alarming, but the idea of being hit by a jagged piece of steel. You hear the whistle of the shell coming, you crouch down as low as you can, and just wait. It doesn’t burst merely with a bang, it has a kind of crack with a snap in it, like the crack of a very large whip.’ On the 28th September, 1917, though, Hulme didn’t crouch. He stood there, in a dreamy moment, and he was killed. When the smoke cleared, some of his comrades were bellowing, others emitting miserable groans. Hulme had simply disappeared. Not a scrap of clothing, nor a shred of that burly, lusty body was left.

Here we move further from the sham certainties of history, deeper into Hulme’s beloved speculations. For in that moment before death, between the whistle and the crack, we’d like to imagine his mind cycling back through his short, sharp life, falling now on the figure of Wyndham Lewis, hanging upside-down on the railings at Soho Square after a row over a girl, now on the crow-like visage of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, his dear friend, dead not yet two years, now on his lover Kate Lechmere’s cyanope smile. And as the shells plunge and shriek like buck-shot birds, we imagine his mind going back to the night when, aged nineteen, he was sent down from St John’s College, Cambridge.

It was late and the boathouse was on fire, the flames tonguing the black Cam. Two policemen wrung river water from their jackets, shaking their fists and whinnying while a college porter waved his feet in the air, his upper half wedged in a dustbin. A rower stood in the light of the flames, his singlet and shorts dark-spattered, one hand clasped to a bloody nose. Two girls sprawled on the bright grass, sobbing. Hulme was swimming in the dark water, pulling his long body through the velvet iciness of the river, because he knew he had gone too far, and he would not feel this water, this river, again. Under the moth-eaten blanket of the sky he swam, and he felt the vague grief of the night, and the ruddy face of the moon leant over the fence of trees that lined the river like a red-faced farmer, watching him. He swam on.

Esmond stops and sighs again. It is seven in the morning. He stands, stretches and looks out for a moment onto the piazza below. He turns out his desk light and shuts the door of the studio.

Suico Atlantico Hotel, Lisbon

15/4/38

Dearest Es –

I wonder if you’d given up on me? There is, I understand, a small mountain of unopened mail waiting for me in Praterstraße; whether some are yours or not I don’t know. The house is being looked after by our neighbours, although the downstairs windows have been broken and the statues in the garden smashed. The last letter I read was from early in your Florentine days. You sounded miserable. I do hope things have improved. I’m sorry I didn’t write back — I’ve always been a dreadful correspondent.

Mutti and papa left for Lisbon two weeks ago. They’d been in Switzerland waiting to see which way the wind would blow. It’s one thing you can say for papa — he’s careful. Moving out of Leopoldstadt was my own concession to caution. I bunked up with Charlie Campbell — do you remember him from Emmanuel? He’s over on some sort of exchange programme teaching papyrology at the university. Put me up in his drawing room. Jolly decent of him. I earned my keep by bowling leg-breaks at him in the corridors of the Faculty of Ancient History. At least I took something from my time in England. I think I loved cricket almost as much as I loved you. Helps keep off the Kummerspeck too!

We told everyone that I was a cousin of Charlie’s over from the UK. I wore his clothes, spoke bad German with an English accent, ordered my tea with milk. But when the worm von Schuschnigg rolled over, and the true extent of the whole Heim ins Reich thing came out, it began to get hot. I left Vienna at night, wrapped in Charlie’s ulster, three days after the Anschluß. I took the train to Innsbruck where I fell in with a gang of Jewish students with pretty much the same idea — escape, get away from that vile little man, his swarm of vile little men. I followed my parents to Lisbon. There were people on the border — not good people, no one I could see doing it for anything but money — and they ferried us across. A week in St Gallen, then Geneva, then a night train to Genoa.

Can’t tell you how much it bucked me up just to be in the same country as you. I even dreamed, for a moment, of hopping off in Milan, taking a train for Florence and turning up on your doorstep. If only to see your face. But that hereditary caution …

It feels like things are rushing towards a ghastly end, as if everything is coming apart like something from Yeats. ‘The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.’ That was it, wasn’t it? I watched those violent men on the streets of Vienna, ugly snarls on their faces, and I knew that no good would come of Europe, that we are entering the new Dark Age, and those who would live must flee.

Читать дальше