He talked about some of the unfortunate lapses of discipline Karel had witnessed and suggested that soldiers in such cases were unsuited to their roles, and who after all could blame wolves set to guard sheep?

Karel at one point interrupted to wonder aloud if the Party had done all it wanted to do and was ready to stop.

There was no answer in the darkness. Then Kehr said in a low voice that all they’d done so far was impose the illusion of order, as though they’d laid a slab of glass over a whirlpool.

The people, he went on after a short silence, were always more malleable than expected. They were now habituated to government by surprise, to believing the situation too complicated for the average citizen to comprehend and too dangerous to talk about. They worked hard to live by the rules, and the Party changed the rules, slightly but enough to continue to make obedience compelling work. The appropriate image, he suggested, might be the blind man who continually had to negotiate his way past rearranged furniture.

Of course, some complained, Kehr told him. Most remained where they were: removed from politics.

What about the partisans? Karel asked. He knew who Kehr was talking about: his neighbors, his father, himself, before his naming of Albert. The partisans, Kehr said, believed, as did the Civil Guard, that there was more latent opposition to the Party out there than anyone might think, ready to be agitated into motion.

The partisans understood violence, Kehr said. They understood a central point: that violence was the only way to create a hearing for moderation. And, of course, they didn’t accept the consequences of their actions unless they were caught: they didn’t stay around to take the punishment.

Within everyone there was a little man claiming Common Sense and Common Decency, Kehr said, but there came a point when people became used to even the unnecessary brutalities. Did Karel ever wonder at what point people would say, of the steps the Party felt compelled to take toward national solidarity, “No, not that”? Did Karel know that all around him people demonstrated that there was nothing they would not stand for? Karel pulled the pillow over his head. Did Karel know that feeling Kehr remembered from long ago, the feeling he’d never forgotten, when he first understood that all sorts of things that had been supposedly forbidden, impossible, and criminal seemed more and more natural, more and more possible, to this new version of himself?

Karel was standing at the stove preparing some simple pastries Kehr had shown him how to make called Prisoners’ Fingers while Kehr worked at the kitchen table, every so often taking a break to continue what he called “our discussions.” Karel rolled the dough with dirty hands and didn’t retain much of what was being said. He thought about Leda and how much she suspected. He’d asked if he could write to her, and Kehr had said that right then the mail in their area wasn’t moving in any direction.

Kehr talked about violence and aesthetic standards, and when Karel’s interest was flagging completely he asked what Karel thought should be done with Leda’s journals.

Karel turned so quickly one of the pastries made a cricketlike hop and stuck to the wall before rolling off. Kehr was incompletely successful in hiding his pleasure. He repeated the question.

“You have her journals?” Karel asked stupidly.

“We do,” Kehr said. “A search of the house turned them up. We’ll save them for her, naturally. I just thought you’d be interested.”

In the other room the ringtail was tapping on something with his claws as if working on a typewriter. “I am,” Karel said.

They were going to be going over there this afternoon, Kehr said. Karel was welcome to come.

All the way there Karel felt guilty and nervous. The house was double-padlocked BY ORDER OF THE NATION AND THE CIVIL GUARD and Kehr had the keys. While he got to work with them Karel waited on the front steps. Neighbors peeked from behind blinds and curtains.

Kehr opened the door and went in. He moved some packing boxes from the hall and led Karel to Leda’s room and hefted a shallow box off the desk and put it in Karel’s arms. Then he left the room.

This was wrong. Karel knew it. The dresser had been dragged over and the floor molding behind it pulled out. He could see the hole where she’d kept the journals. These were things she had a right to keep to herself, things she could have shared with him if she’d wanted to. But he was excited at having secret access: Leda herself answering all his questions. How did she feel about him? How much did she think about him? Was there anybody else?

And suppose this was his only chance? She was gone. Suppose this was the only Leda he’d ever get again?

Kehr seemed to be bumping around innocuously downstairs. It wasn’t clear to Karel what he was doing.

There was still time. He could leave it all, let Kehr know he knew he had no right to do this. But what if she’d gotten herself into trouble with what she’d written here? If Kehr or somebody had read it? He’d need to warn her then, or plead her case. He hefted the box higher and said, “That’s true,” as if saying it would make it so, and left the room and headed downstairs.

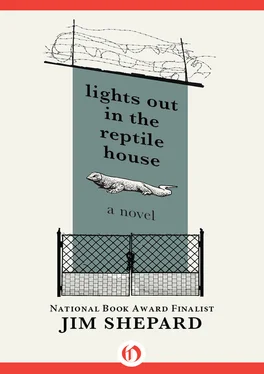

He spread everything in front of him on his desk and then with suppressed excitement limited himself to the first of the three spiral-bound notebooks. It was filled with pencil drawings. She had titled some of them: Nicholas, Nicholas and David, Nicholas Asleep, Sad Crow and Rabbit, Dog, and then, filling him with hope and joy, K’s Hands . That one featured three sets of hands orbiting a lizard’s foreleg and claw: one with the right hand curled inside the left (washing?), another hefting a rock, and the third operating a nooser. The design puzzled and bothered him. Was she comparing his hands to the lizard’s? Did she think of him in terms of the Reptile House? She’d done the foreleg from life: the toes ending in the sharp curve of claw, the keeled scales. He tried to push ahead but found himself flipping back to that page, unable to stop looking.

He left a piece of paper there as a bookmark and paged quickly along looking for other parts of his body. He came across an old man with Albert’s hair and tired expression, dressed in a zoo smock. He was holding a bird in one hand and a gun in the other. His legs ended at the ankles. Whether he was supposed to be standing in something or Leda couldn’t draw feet Karel couldn’t tell. It looked like Albert, and the connection disturbed him. More and more he was having the queasy feeling that his whole world was interconnected behind his back. The bird had a leafed branch in its beak. There were lines radiating out from the man’s head. Holiness? A thought? A headache? A vulture or other huge bird sat in space above him. She’d drawn NUP on its breast, the letters curved to fit.

He shut the notebook. He’d look at the drawings more later. He wanted more of her voice and thoughts.

On the first page of the second notebook it said, This is my letter to the world that never wrote to me . — Leda Schiele . A sheaf of pages following that had been torn out. The first entry remaining had no date but was numbered 17, at the top of the page.

Elsie was right: I hurt her feelings, and where did I get the right to do that? I’m never happy with anyone else but where do I get the idea I’m so great? From the bottom up I need to work on myself. I say I want to be an artist but what do I do to prove it? I hardly draw anymore and I have zero patience for my books. We learned to draw pretty well in school even though our art mistress was mediocre and very young, and what’ve I done with what I learned? At least I’ve stopped turning out complete trash like I did with Mr. G. Sometimes the other thing that cheers me up is that I think I’m learning, and that’s the main thing. The rest should come by itself.

Читать дальше