“You’re bea—”

Blood was coming out of her nose. Jack noticed it the moment I did, feeling at her lips for whatever was so wet.

“I’ll get a towel.”

But it got thicker, the red.

She collapsed. I crawled desperately over to her, put a pillow under her head. Held her hand. She squeezed.

“Fuck. .” She was terrified when she asked me what was happening to her, dazedly.

“I don’t know, I don’t know!”

I searched around for my phone on the floor, but couldn’t find it. My legs wanted to seize. I couldn’t find it. I found her phone; it was dead. I let go of her hand and got up to turn the lights back on. The keys to the Rambler were still in my coat. She said something to me, or maybe nobody, but it was so faint I didn’t quite understand it. I was thinking of the fastest way to the hospital. I was going to get help.

“Jack?”

I dropped the keys.

“Jackie!”

But she wasn’t answering anymore.

“No, no, no, no, no. .”

I held her hand in the middle of the circle.

I didn’t know what to do.

Eyes slightly open like she was sleepily looking up at me.

Blood starting to dry on the side of her face, where it’d run.

She was so still, she wasn’t breathing anymore.

I started to scream for help. .

I spent Christmas day on the bank of the Willamette, watching the current. I hadn’t slept, because each time I closed my eyes, I saw her. I decided I wouldn’t yet tell the rest of the band, because they were home with their families, and I needed to hold onto the grief a little longer. I thought of Mensa. The things that happen around you, to you, and with that frequency, you’ve got to wonder if it’s somehow your fault. If you attract pain. I was drinking instant matcha I’d mixed into a thermos, shivering but not giving a shit. Hot breath drifting out of me like smoke. I didn’t even care that this was the end of the band.

I thought of Jack’s present, unopened at the base of the tree. An Elvis bust I’d found at a vintage shop in southeast. Above, the sparse holiday traffic on the Hawthorne bridge continued on, oblivious.

Jack had come a long distance, no closer to what she’d set out to do.

It made all that effort appear meaningless.

I skipped a rock over the water, holding in the feeling.

Wanting something tangible to hate and coming up with fuck-all.

We were waiting to get tattooed in front of the vegan mini-mall on SE Stark. We’d just returned from driving around the coast in a rental van and decided to celebrate. Jack was chain smoking. I was staring at nothing, somewhere between the sidewalk and the street. Paloma coughed, her voice still in recovery from all the onstage screaming. Ira was eating a sandwich from the grocery store next door.

“You’re already hungry?” Jack put out the cigarette on the wall, flicked it away.

“Whatever,” Ira said, making ‘nom’ sounds.

“Where does it all even go?” We’d just eaten at Paradox, and Ira put away an entire plate of food along with an appetizer and whatever we hadn’t finished off of our plates. Her stomach was like a bottomless pit, and yet, she remained the smallest lady of the group.

Inside the shop there was the constant hum of tattoo guns.

People prone in various positions, getting carved.

We waited on the benches across from the check-in desk.

Ira flipped through a magazine.

Paloma looked at a corkboard, where articles and pictures were tacked up.

My brain felt liquid.

Jack was at the center of the shop, bathed in light, hovering a foot off the ground.

Ira asked the group, “First tattoo?”

“A star.”

“A flower.”

“A dick with wings.”

“Whaaaatt?”

“It was supposed to look like a butterfly — we were sixteen and shitfaced,” said Jack.

“Stick ‘n’ poke?” Paloma cleared her throat.

“You know it.”

“Okay, okay,” I said. “Worst?”

“I got this.” Jack pulled up her sleeve: on her shoulder, the poorly drawn XXX-labeled bottle, inscribed “White Trash” below it. The art’s uneven and faded, blurry. “I don’t even know where it came from. I remember getting shit-housed at this parking lot rave-thing in southeast, and waking up the next morning with my arm all bandaged up.”

Ira inspected it, acting like she’d never seen it before. “That’s pretty bad.”

“Yeah, what the fuck?” I said.

“Virginia in a nutshell, dudes.” Jack shrugged.

One of the tattooers glanced up and shook his head at us, and went back to the outline he was shading.

“I’m bored,” said Paloma. “Feel like I haven’t had much to do this whole time.”

“It’s the come-down,” Jack said.

“Let’s get a ‘Before’ photo together.” Ira held her phone out, camera inverted.

“I’m fucking tired.” I yawned.

We leaned in, waiting for the picture to take. Smiles start to hurt when you hold them long enough.

“Cheese,” said Ira.

I was frozen in the image, throwing up horns and sticking out my tongue.

“That’s a face that gives no fucks.”

“Ella.”

“Huh?”

“Worst tattoo for me was—” Paloma began.

“Ella, you’re up!”

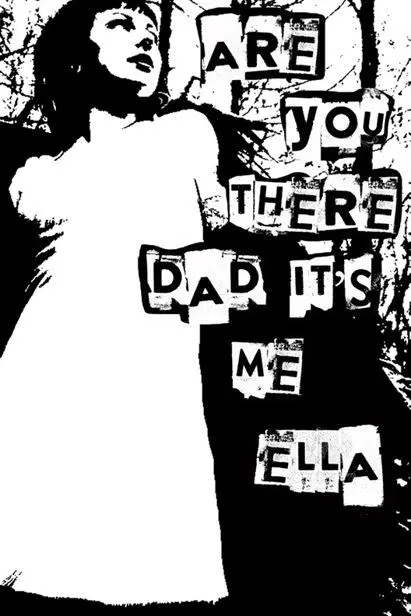

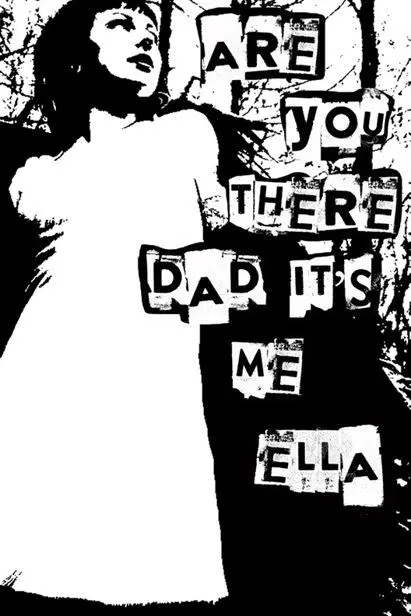

ARE YOU THERE DAD? IT'S ME, ELLA

Father, daddy, dad, pa, pop. Mister. Pablo Alberto Jimenez Marquez: I never knew what to call him because I never knew him. I was born to the old man and my mother, Giselda Ofelia Nunez Espinoza, in 1985. Just as well, these relations were only biological. Like a generation erased, it was my grandparents that took me in.

I was Isobella as a child, when they were nearly children themselves. Fourteen years their younger. I was Ella when my grandmother picked me up and I cooed, and that became the name that stuck most.

Did I have a happy childhood? That depends, is it possible to be happy when raised by an entire family? After all, Pablo and Giselda had made plans to elope when I was a secret on the way. But in Mexican families, secrets never stay secrets for long. My father had been the first of his family to make it past middle school. My mother had to drop out, to avoid the shame of her growing belly. It was a different time, so they say. This is what little I’ve been told, the way family will blur the uncomfortable.

What I do know is, one day they weren’t able to make it work. My father’s family moved, and we never heard from him again. But not before he’d become an idea, something I was sure was real, like a mall Santa, the Easter Bunny, Dios . . a mystery.

I grew up in Los Angeles, a queer, Mexican-American woman.

Even before my mother passed away, she was seventeen, I used to write letters to the old man. First with crayons, then pencils and pens, a typewriter. Every now and then, I’d write a new one and take it to the mailbox. I’d address it “To Dad,” and the letters would get picked up. I would wonder why he never replied, if maybe the letters had gone to the wrong father. My aunt told me it was more likely they’d been delivered to the trash, because I was too young to understand the necessity of a proper address and postage.

But I continued to write them. I kept the letters in a stack, kept my now imaginary father updated. When the stack got too tall, I started to put them into a suitcase. Then a day came when I wanted to place a new letter into the suitcase and couldn’t find it. I was panicking, looking everywhere in my room — even places it couldn’t possibly fit. It turned out that a cousin was going on a holiday and needed a carry-on, and my grandmother had volunteered the suitcase and emptied the letters into the trash, because they hadn’t looked all that important. The letters were long gone. .

Читать дальше

![Lady Tiffany - Милость короля [СИ]](/books/397137/lady-tiffany-milost-korolya-si-thumb.webp)