She reads from notes in controlled terror. If you think the lake is big you should see the sea. It’s three-quarters of Earth. And that’s just the surface. Someone throws a pencil. The creases on Ruby’s forehead sharpen. Land animals live on ground or in trees rats and worms and gulls and such. But sea animals they live everywhere they live in the waves and they live in mid water and they live in canyons six and a half miles down.

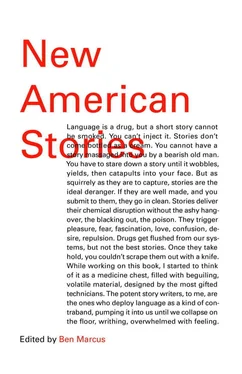

She passes around a red book. Inside are blocks of text and full-color photographic plates that make Tom’s heart boom in his ears. A blizzard of toothy minnows. A kingdom of purple corals. Five orange starfish cemented to a rock.

Ruby says, Detroit used to have palm trees and corals and seashells. Detroit used to be a sea three miles deep.

Ms. Fredericks asks, Ruby, where did you get that book? but by then Tom is hardly breathing. See-through flowers with poison tentacles and fields of clams and pink spheres with a thousand needles on their backs. He tries to ask, Are these real? but quicksilver bubbles rise from his mouth and float up to the ceiling. When he goes over, the desk goes over with him.

—

The doctor says it’s best if Tom stays out of school and Mother agrees. Keep indoors, the doctor says. If you get excited, think of something blue. Mother lets him come downstairs for meals and chores only. Otherwise he’s to stay in his closet. We have to be more careful, Tomcat, she whispers, and sets her palm on his forehead.

Tom spends long hours on the floor beside his cot, assembling and reassembling the same jigsaw puzzle: a Swiss village. Five hundred pieces, nine of them missing. Sometimes Mr. Weems reads to Tom from adventure novels. They’re blasting a new vein down in the mines and in the lulls between Mr. Weems’s words, Tom can feel explosions reverberate up through a thousand feet of rock and shake the fragile pump in his chest.

He misses school. He misses the sky. He misses everything. When Mr. Weems is in the mine and Mother is downstairs, Tom often slips to the end of the hall and lifts aside the curtains and presses his forehead to the glass. Children run the snowy lanes and lights glow in the foundry windows and train cars trundle beneath elevated conduits. First-shift miners emerge from the mouth of the hauling elevator in groups of six and bring out cigarette cases from their overalls and strike matches and spill like little salt-dusted insects out into the night, while the darker figures of the second-shift miners stamp their feet in the cold, waiting outside the cages for their turn in the pit.

In dreams he sees waving sea fans and milling schools of grouper and underwater shafts of light. He sees Ruby Hornaday push open the door of his closet. She’s wearing a copper diving helmet; she leans over his cot and puts the window of her helmet an inch from his face.

He wakes with a shock. Heat pools in his groin. He thinks, Blue, blue, blue.

—

One drizzly Saturday, the bell rings. When Tom opens the door, Ruby Hornaday is standing on the stoop in the rain.

Hello. Tom blinks a dozen times. Raindrops set a thousand intersecting circles upon the puddles in the road. Ruby holds up a jar: six black tadpoles squirm in an inch of water.

Seemed like you might be interested in water creatures.

Tom tries to answer, but the whole sky is rushing through the open door into his mouth.

You’re not going to faint again, are you?

Mr. Weems stumps into the foyer. Jesus, boy, she’s damp as a church, you got to invite a lady in.

Ruby stands on the tiles and drips. Mr. Weems grins. Tom mumbles, My heart.

Ruby holds out the jar. Keep ’em if you want. They’ll be frogs before long. Drops shine in her eyelashes. Rain glues her shirt to her clavicles. Well, that’s something, says Mr. Weems. He nudges Tom in the back. Isn’t it, Tom?

Tom is opening his mouth. He’s saying, Maybe I could— when Mother comes down the stairs in her big, black shoes. Trouble, hisses Mr. Weems.

Mother dumps the tadpoles in a ditch. Her face says she’s composing herself but her eyes say she’s going to wipe all this away. Mr. Weems leans over the dominoes and whispers, Mother’s as hard as a cobblestone but we’ll crack her, Tom, you wait.

Tom whispers, Ruby Hornaday, into the space above his cot. Ruby Hornaday. Ruby Hornaday. A strange and uncontainable joy inflates dangerously in his chest.

—

Mr. Weems initiates long conversations with Mother in the kitchen. Tom overhears scraps: Boy needs to move his legs. Boy should get some air.

Mother’s voice is a whip. He’s sick.

He’s alive! What’re you saving him for?

Mother consents to let Tom retrieve coal from the depot and tinned goods from the commissary. Tuesdays he’ll be allowed to walk to the butcher’s in Dearborn. Careful, Tomcat, don’t hurry.

Tom moves through the colony that first Tuesday with something close to rapture in his veins. Down the long gravel lanes, past pit cottages and surface mountains of blue and white salt, the warehouses like dark cathedrals, the hauling machines like demonic armatures. All around him the monumental industry of Detroit pounds and clangs. The boy tells himself he is a treasure hunter, a hero from one of Mr. Weems’s adventure stories, a knight on important errands, a spy behind enemy lines. He keeps his hands in his pockets and his head down and his gait slow, but his soul charges ahead, weightless, jubilant, sparking through the gloom.

In May of that year, 1929, fourteen-year-old Tom is walking along the lane thinking spring happens whether you’re paying attention or not; it happens beneath the snow, beyond the walls — spring happens in the dark while you dream — when Ruby Hornaday steps out of the weeds. She has a shriveled rubber hose coiled over her shoulder and a swim mask in one hand and a tire pump in the other. Need your help. Tom’s pulse soars.

I got to go to the butcher’s.

Your choice. Ruby turns to go. But really there is no choice at all.

She leads him west, away from the mine, through mounds of rusting machines. They hop a fence, cross a field gone to seed, and walk a quarter mile through pitch pines to a marsh where cattle egrets stand in the cattails like white flowers.

In my mouth, she says, and starts picking up rocks. Out my nose. You pump, Tom. Understand? In the green water two feet down Tom can make out the dim shapes of a few fish gliding through weedy enclaves.

Ruby pitches the far end of the hose into the water. With waxed cord she binds the other end to the pump. Then she fills her pockets with rocks. She wades out, looks back, says, You pump, and puts the hose into her mouth. The swim mask goes over her eyes; her face goes into the water.

The marsh closes over Ruby’s back, and the hose trends away from the bank. Tom begins to pump. The sky slides along overhead. Loops of garden hose float under the light out there, shifting now and then. Occasional bubbles rise, moving gradually farther out.

One minute, two minutes. Tom pumps. His heart does its fragile work. He should not be here. He should not be here while this skinny, spellbinding girl drowns herself in a marsh. If that’s what she’s doing. One of Mr. Weems’s similes comes to him: You’re trembling like a needle to the pole.

After four or five minutes underwater, Ruby comes up. A neon mat of algae clings to her hair, and her bare feet are great boots of mud. She pushes through the cattails. Strings of saliva hang off her chin. Her lips are blue. Tom feels dizzy. The sky turns to liquid.

Читать дальше

![Женя Джентбаев - neo futura [stories]](/books/692472/zhenya-dzhentbaev-neo-futura-stories-thumb.webp)