Caroline stood up straighter. “There’s been mice around. Seems like a sensible way to get rid of them.”

Mildred huffed. “I’ve not seen any mice around my stoop.”

All night Caroline worried about what Mildred would be saying to the neighbors. She’s giving meat to a cat when people are starving. Letting filthy animals in her house. Going a little batty living there all alone. The thought of people talking about her made Caroline’s skin feel tight, as if someone were pulling a million strings attached to her million pores.

The next morning, she began to clean the house. In the last several weeks she’d let her daily chores lapse. Now, the dirt and bits of leaves on the front walk and the sticky film on the kitchen floor inspired a mild panic. She scrubbed the tiles, shook rugs, dusted tables, swept the sidewalk. Then she remembered the windowsills. The first night she heard the cat, she’d pulled back the drape and noticed an accumulation of dead flies and spider webs. Now, as she tugged open each window, it occurred to her the cat may have been out there hours, even days, before she noticed him because she always kept the drapes shut to guard against sunlight fading her furniture. She thought of her daughter Addie, her favorite, who’d confided to Sophie, who later told Caroline, that she didn’t like to bring friends home because Caroline made them nervous. Was she so formidable?

She left the drapes open. What did it matter if her couch faded a shade or two? And who could guarantee she would live long enough to notice?

Caroline was cleaning out the refrigerator — the new electric kind she bought just before Frederick fell ill — when Eva and Sophie arrived. They were arguing as they came in the door. Neither seemed at all surprised to see her cleaning, which relieved her sense of being the wrong person in the right body.

“Mother,” Sophie said, “Mrs. Putramack waylaid us in the backyard. She said you’ve been feeding some cat, a stray.”

“Is she talking about the cat I saw last time? The black one?” The note of displeasure in Eva’s voice made Caroline angry. She also noted the surprise, remembering the plate and saucer Dobry must have seen.

“I don’t know what that old woman wants me to do — firecracker it?” After Frederick died last summer, some kids put a stray cat in a cardboard box on the Fourth of July, then stuck lit firecrackers through holes in the box. Addie, who’d been helping Caroline sort paperwork, saw the boys do it. She chased them off, but too late, and came back in crying, saying she wished her father were here, he’d make those boys sorry. Caroline patted her back and looked out the window at the way orange shadows played against the house next door. For several days after that she’d felt frightened and out of place, as if she’d woken up in a world that looked like hers, but upon closer inspection was more like the props to a play, with hidden gears grinding behind paper-thin doors and windows without glass.

Before the girls left, Caroline said, “I thought Dobry was going to finish burning my leaves,” a more imploring tone in her voice than she’d intended.

“He’ll come by Saturday, Mother,” Eva said. “I promise.” Caroline never knew whether to take Eva’s kindness as a sign of love or fear.

Later, Caroline was cleaning upstairs and opened Frederick’s wardrobe. The smell of long-confined cedar filled the air. With the weather getting cold, she knew she ought to take his wool coats and suits to the Salvation Army. She was afraid, though, that one day she would pass a man wearing Frederick’s brown and green checked overcoat and she would — for just a moment — think him still alive, then have to remember that, of course, he was not.

Caroline didn’t want to marry any of the men her mother had chosen. She resented being discussed and measured like a piece of cloth. She wasn’t something this man was going to wear around his skinny neck. But it felt impossible to avoid the marriage. Where would she go? How would she support herself?

One Saturday morning — another warm, wet day, the rag on her face — Caroline’s father called her down to breakfast. He sat across from her mother at the dining room table in his undershirt, his short, shriveled appendage in full view. Caroline knew this annoyed her mother, who preferred he keep the embryonic limb out of sight.

Her father’s arm made Caroline think of dried fruit, baked in the sun until all the moisture had leeched out. After she learned of gangrene, the way it begins at the spot of injury and, if unchecked by amputation, migrates toward the center of the body, it seemed impossible the desiccation would stop of its own accord. She began to study her father’s shoulder and the right side of his neck for signs of wrinkling or flaking skin.

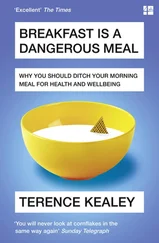

Caroline slid into her seat. The dining room table was set with the morning dishes, blue forget-me-nots on a yellow plate. Her teacup was full of orange juice because her mother disliked the way a juice glass interrupted the place setting, and her plate held toast and two eggs, poached, because that was the only way civilized people ate eggs. A cut-glass bowl in the center of the table held blackberry jam. Caroline didn’t particularly like it, but she always ate it because her mother thought jam messy and her father considered it indulgent.

Caroline carefully ran her knife along the edge of the bowl, and spread the jam on her toast. It was in returning the nearly clean knife to the bowl that a black spot appeared on the table. Her mother’s eyes didn’t move. Her father’s features remained still. The words, when they came, seemed to float in from behind Caroline, as if meant for someone else, someone in the neighboring house perhaps, and only through fault of the wind had they found her. You’ve ruined the tablecloth. She didn’t even know who said them. The words were too distinct to be her mother’s, the voice too high to be her father’s. Caroline looked up and her parents were sipping their coffee. Then, in her marbled speech, Caroline’s mother said to her father, “See, I told you she is making a bad impression. She’s as clumsy as you with that stump.”

Her father spoke slowly, looking directly at her mother, “Maybe they’re afraid of you.” He invoked an old folk saying. “The deaf cannot be trusted.”

At the Salvation Army Caroline lay the coats and hats, the suits and shoes with laces tied together, on the desk. “I want someone to have these, someone who needs them.”

The man at the desk, a face like a well-worn rock, nodded. “Sure.”

Caroline watched him sort each item into different boxes, the suits folded against all good sense on top of work shirts and canvas pants.

At home the cat sat facing the door. “What are you doing? Hm? Get away from there, go.” It was the end of October and Caroline thought of Halloween. She’d given out treats when Frederick was well — popcorn balls, cookies, and often, in her neighborhood, pieces of sweet bread or paczki — but after he became ill, she hadn’t felt like it, causing her house to become the target of hooligans who tossed eggs at the front door, or left dog excrement in a bag of fire on the porch.

This year the expectation of harassment did not trouble Caroline as it had before. Nothing felt as it had when Frederick was dying, or right after he’d passed, the day Adelaide sat crying over the damn cat in the box. Now it seemed instead that the person turning the controls on her found the boys’ petulant punishment amusing. They wanted their sweets, and this was her sentence for not providing them. Unlike the cat, who’d done nothing, she had refused them a treat. Fair enough. She would simply put gloves on, throw the paper bag away and scrub the egg off her windows. No harm done.

Читать дальше