“I have to cut stuff back,” Molly says.

“It’s too late,” Helen shrugs. “You’ve lost control.”

Molly looks at the yard. “We haven’t had time, with the girls.”

“Emma’s in first grade this year, right? You been working?”

Molly shrugs. Simon likes to keep alive the myth that she hasn’t given up on a Ph.D.

“So how’s it going with the crazy Christians?” Dugan asks.

Simon laughs. “The usual. Death threats mailed care of my publisher. Oh, the new thing is Kate’s going to hell.” He tells them about Sarah.

“That’s why the East Coast is better for people like us,” Helen says.

Dugan’s face tightens, deepening the creases that divide his narrow cheeks into sections like a sliced loaf of bread. “Is it that bad, Molly?”

“Well, I wouldn’t say we’re terribly popular in the neighborhood. No one except Sarah’s mother gives me more than a perfunctory hello.”

“Which is ironic,” Simon says, “since she’s the craziest Christian of them all.”

Molly scowls. “Be nice. The Randolphs are good people.”

“Are you sure she knows about the book?” Helen asks.

“Everybody knows. This neighborhood has the Ford assembly line of rumor mills.”

Helen looks at Dugan meaningfully. She’s published several essays on atheism with a feminist twist. Simon smells a book in them, another reason to worry about her getting snatched away to the Ivies.

“Could be fun,” Dugan raises his eyebrows. “You enjoy pissing people off.”

The doorbell rings and Molly goes through the house to answer.

Elizabeth is there with Adoo to pick up Sarah. Molly invites her in, but Adoo remains on the porch.

“Now that it’s warm, he likes to be outside,” she explains, keeping an eye on him through the storm door. “When he first got here he was afraid of the cold.”

“So he’s adjusting?” Molly asks.

“He’s doing great with English, and he’s teaching me his language.”

“Does he always put those lines on his face?”

“They’re from his tribe. They burn the skin and use a plant sap to dye the scar tissue as it heals.”

Molly blanches. “So it’s permanent?” She puts a hand to her own cheek. “Have you talked to any of the plastic surgeons around? Maybe they could do laser removal.”

“Oh no!” Elizabeth exclaims. “I wouldn’t want to take that away from him. He had a whole life before us, and I want him to hold on to it.” She pats Molly’s shoulder. “It’ll be okay. It’s all in Jesus’s hands.”

As the girls come downstairs, Adoo opens the door and presents a garden snake to them with a big smile. Sarah screams and clutches at her mother.

“Sarah!” Elizabeth snaps. “That’s enough.” She unwinds Sarah’s arms from her waist and gently pushes her backward, then takes the snake, muttering a foreign word to Adoo that sounds like “beda,” and releases the animal into the bushes. “Please tell Adoo you’re sorry.”

Sarah wrinkles her nose. “Sorry.”

“In his language, please.”

“Minto,” she mumbles.

Simon comes in from the kitchen. “What’s the uproar?”

Elizabeth explains Adoo’s fondness for snakes, smiling at him as if he’s been discovered to like cubing three-digit numbers in his head.

“He’s probably an animist,” Simon says. “Snakes are often seen as role models. He may even worship them as gods.”

Sarah scrunches her face into exaggerated disbelief. “The Bible says snakes are the devil.”

“The serpent in the Bible is a symbol of evil,” Elizabeth corrects. “He’s a form the devil took. Regular snakes are just snakes, all God’s creatures.”

“How do you know the difference?” Emma has come into the hall, her lips rimmed in blue from an unapproved popsicle.

Everyone looks at Molly. Why is she supposed to have an answer? “Go wash your face,” she orders. “And stay out of the popsicles.”

That night when Simon goes to kiss the girls good night, he finds them on their knees, fingers laced together.

“Pascal’s Wager,” he explains to Molly. “Sarah told Kate she should pray to God because nothing bad will happen if she’s wrong, but if she doesn’t pray and God exists, she’ll go to hell.”

Kate looks sheepish. “I’m sorry, Daddy. Are you mad at me?”

“No, of course not. Why would I be mad?”

“Because you think praying is stupid.”

“No, he doesn’t!” Molly repeats her canned speech on different beliefs being okay.

“Do you believe in God, Mommy?”

“I’m still thinking about it,” Molly says, “I do know this, though: I’m not going to hell and neither is Emma or your father. If there’s a God, He’s more interested in what we do than what we think.”

“How do you know?”

Simon sits on the bed and puts his hand on Kate’s knee. “Just think about it, honey. The idea of God is that he created all other beings, right?”

She nods.

“So if he created us, including our brains, then he must know how we think, sort of like the people who invented computers know how they work. It follows that if you pray without really believing in God, then God will know you don’t believe, and it won’t matter what you do.”

“So I’m going to hell even if I pray?”

Molly shoves Simon out of Kate’s room. Downstairs she tells him to lay off the logic. “You’re scaring the pants off that poor kid.”

At one a.m. Molly wakes to sounds in the hall. Kate lies outside their bedroom door clutching Grubby, the musical bunny she’s had since infancy.

“What’s the matter?”

“Nothing. I was just hot.”

Molly takes her back to her own room and they lie together like gears in the twin bed. Kate tucks Grubby under her chin and rubs his foot against her lips. “Mom, can I go to church with Sarah and her family? She invited me.”

“Sure, why not? It’s fun to have new experiences.”

“I love you, Mom.”

“I love you too.”

While Kate’s breath slows and deepens, Molly does the math in her head. Twenty-nine thousand, seven hundred and sixty-four. The paltry number shocks her, so Molly does it again more carefully, but comes up with the same answer. If Kate lives to be ninety, that’s how many days she has left.

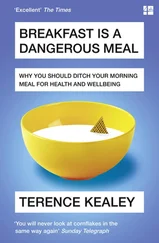

The next morning, Molly feels as if she slept in the stockade. Simon cheerfully greets her at the breakfast table. “Where were you?”

“Crammed into Kate’s bed. How about this for your next book? Parental fatigue is the source of religion. We don’t need God to explain things to ourselves. We invented him to shut the children up.”

Simon laughs until she tells him about Kate wanting to go to Sarah’s church.

“Isn’t it enough they’re trying to convert that poor pagan kid, they want mine too?”

“You’re trying to convert every Christian into an atheist,” Molly accuses. “What’s the difference?”

“Technically, I’m an agnostic.”

“That’s not what your book says.”

Molly sits down and splays her hands on the table. “Has it ever occurred to you God is a comfort to kids? He answers a lot of tough questions.”

“What we need is somewhere to take agnostic kids. I want to invite Elizabeth’s brood to a big room where we all sit around singing songs about logic and reading the Bible for inconsistencies.”

“You work there. It’s called a university.”

Simon waves this off. “I get them too late. The brainwashing has already taken hold.”

“Yes, except Kate’s being raised by us. For us God is like the Easter Bunny and Santa, maturity will take care of him.”

“That’s only because adults agree Santa doesn’t exist. As long as there are people like the Randolphs, that’s not going to happen with God. The girls are going to get confused.”

Читать дальше