“Over there, Dad,” Akhil said, pointing at something Amina couldn’t see, and Thomas gripped her by the shoulders and propelled her forward.

“Babu!” He clapped an old man on the back. “Good to see you!”

Wrapped in a bulky dhobi and skinny as ever, Babu smiled a toothless smile, his resemblance to a malnourished baby belying his ability to toss large objects onto his head and carry them through crowds, as he did with all four of the family suitcases. Outside the station, Preetham, the driver, loaded the freshly polished Ambassador, while beggars surrounded them, pointing to the children’s sneakers and then to their own hungry mouths, as if their appetites could be satisfied by Nikes.

“Ami, come!” Kamala called, opening the car door, and once everyone else had taken their places (Preetham and Thomas in the front seat, Akhil, Kamala, and Amina in the back, Babu standing proudly on the back fender), they began the four-block ride home.

Unlike the rest of the family, Thomas’s parents had long ago left Kerala for the drier plains of Tamil Nadu. Settling in a large house at the edge of town, Ammachy and Appachen had opened a combined clinic (she was an ophthalmologist; he was an ENT), and before his sudden death by heart attack at the age of forty-five, they saw 70 percent of the heads in Salem.

“A golden time,” Ammachy would spit at anyone within distance, going on to list everything since that had disappointed her. Top of her list: her eldest son choosing to marry “the darkie” and move to America when she had arranged for him to marry Kamala’s much lighter cousin and live in Madras; her youngest son becoming a dentist producing “the no-brains” instead of becoming a doctor and producing another doctor; the many movie theaters and hospitals that had since sprung up around the house, penetrating it with noise and smells.

“Bloody Christ,” Thomas breathed as they turned onto Tamarind Road, and Amina followed his gaze. “You can’t even see the house anymore!”

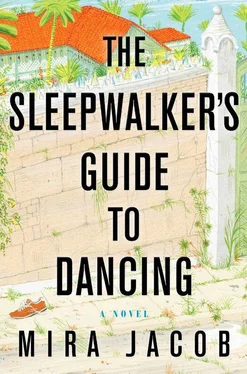

This was true. It was also true that what could be seen, or rather, what could not be ignored, was the Wall, Ammachy’s solution to the changing world around her. Built of plaster and broken bottles, the Wall grew crooked and taller and more yellowed with every visit, until it resembled nothing as much as a set of monster’s dentures fallen from some other world and forgotten on the dusty side of the thoroughfare.

“It’s not so bad,” Kamala said unconvincingly.

“It’s creepy,” Akhil said.

“New gate!” Preetham beeped the horn, and the family fell silent as the gate swung open from the inside, pulling the car and its contents down the driveway.

The house, for its part, had not changed at all, its two stories painted pink and yellow and slanting in the heat like a melting birthday cake. A small crowd had gathered in front of it, and Amina watched them through the window — Sunil Uncle, dark and paunchy; his wife, the wheatish and wimpy Divya Auntie; their son, Itty, head weaving from side to side like a skinny Stevie Wonder; Mary-the-Cook, the cook; and two new servant girls. Christmas lights and tinsel twinkled in the pomegranate trees.

“Mikhil! Mittack!” Itty gurgled as the car pulled in, arm hooking frantically into the air. He had grown as tall as Sunil since their last visit, and Amina waved back, full of dread. Mittack was her name, according to Itty, and excitability was the condition that made him bite her on occasion, according to the family. Amina fingered the faint half-moon on her forearm, sinking a little in her seat.

“Hullohullohullo!” Sunil shouted as the car parked. “Welcome, welcome!”

“Hey, Sunil.” Thomas opened the door, taking long strides across the lawn to shake hands. “Good to see you.”

This was a lie, of course, as neither of the brothers was ever particularly glad to see the other, but it was the only way to properly start a visit.

Sunil fixed a blazing smile on Kamala. “Lovely as a rose, my dear!” He bestowed cologney kisses on her cheek and then Amina’s before turning and clutching his heart. “And who is this ruddy tiger? My God, Akhil? Is that you? Blossoming into a king of the jungle, are we?”

“I guess,” Akhil sighed.

Suddenly, two hands wrapped around Amina’s neck and squeezed hard, crushing her larynx. She pulled frantically at them, dimly aware of her mother patting Divya’s arm in greeting, of the hot breath in her ear.

“Mittack!” Itty let go, patting her head.

“Jesus!” Amina gasped, tears in her eyes. “Mom!”

“Itty.” Kamala smiled. She wrapped her arms around the boy, who grunted and buried his face in her neck.

“Hello.” Divya stood in front of Amina, slight, pockmarked, and branded with the expression of someone expecting the worst. “How was the train?”

“It was nice.” Amina loved the overnight train from Madras. She loved the call of the chai-wallahs at every stop, the smell of different dinners cooking in the towns they passed. “We got egg sandwiches.”

Divya nodded. “You’re feeling sick now?”

“No.”

“Sick!” A voice snapped from behind Divya. “Already? Which one?”

Beneath the heat and the house and the blinking lights, Ammachy sat in her wicker chair on the verandah, sweating rings into a sea-foam-green sari blouse. The two years that had passed since their last visit had done nothing to soften her face. Long white whiskers grew out of her chin, and her spine, hunched by decades of complaint, left her head floating some inches above her lap.

“Hello, Amma.” Thomas’s fingers were firm on Amina and Akhil’s necks as he marched them up the few stairs to where she sat. “Good to see you.”

Ammachy pointed to the roll of flesh that pressed at the hem of Akhil’s polo shirt. “ Thuddya . What kind of girlish hips are you growing?”

“Hi, Ammachy.” Akhil leaned in to kiss her cheek.

She turned to Amina with a wince. “Ach. I sent some Fair and Lovely, no? Didn’t use it?”

“She’s fine, Amma,” Thomas said, but as Amina bent to kiss her, Ammachy snatched her face, pinning it between curled fingers.

“You will have to be very clever if you are never going to be pretty. Are you very clever?”

Amina stared at her grandmother, unsure of what to say. She had never thought of herself as particularly clever. She had never thought of herself as particularly bad-looking either, though it was obvious enough now from the faint repulsion that rippled through the hairs on Ammachy’s lip.

“Amina won the all-city spelling bee,” Kamala announced, pushing Amina’s head forward so that her lips landed openly against Ammachy’s cheek. She had just enough time to be surprised by the taste of menthol and roses, and then she was pulled into the too-dark house and down the hallway, past Sunil and Divya and Itty and Ammachy’s rooms, to a dining room set with tea.

“So train was crowded? Nothing to eat? She’s so happy to see you.” Divya motioned for Kamala and the kids to sit and pushed a plate of orange sweets at them. “She’s been talking of nothing else for a month.”

“Itty,” Sunil boomed, dragging a lumpy suitcase in behind him. “Your uncle is insisting we see what presents he has brought. Shall we take a look?”

“Hullo?” Itty nodded vigorously. “Look? Look?”

“It’s nothing, really.” Thomas took a seat next to Amina.

“Small-small things,” Kamala added.

Ammachy limped in with a scowl. “What is all this nonsense?”

It was: two pairs of Levi’s, one bottle of Johnnie Walker Red, three bags of nuts (almonds, cashews, pistachios), a pair of Reeboks with Velcro closures, a larger pair of hiking boots, two bottles of perfume (Anaïs Anaïs, Chloé), four cassette tapes (the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Kenny Rogers, Exile), two jars of Avon scented skin lotion (in Topaze and Unspoken), several pairs of white tube socks, talcum powder, and a candy-cane-shaped tube filled with marshmallow, root beer float, and peppermint flavored lip balms.

Читать дальше