“I hesitate to say this,” Hay answered, taking off his glasses. He massaged the bridge of his nose. “But I need to ask a favor.”

“Of course I’ll do you a favor, Knudson.”

Hay put his glasses back on. “Are you feeling all right, Milo?”

“I think I am. Yes.”

“The Pentagon needs some help from us.”

“Pardon?”

“The Pentagon. They want war simulations. A bomber-fighter engagement. They asked us to game it out on paper before they commit resources. Rather high-stakes risk/reward is what it is, and they need a strong statistical-algebraic mind. They’ve been very kind to us over my years here.”

“A little jeux de hasard then.”

“Exactly.”

“And a little quid pro quo.”

“Perhaps so. But I’d like you to do it, Milo. They need it soon. It’s not your field, but you’ve got the talent and you’re fast. You could have it done in two days. Your father was a military man, was he not?”

“Yes. Navy.” Andret thought for a moment. “You’re testing me, Knudson, aren’t you?”

“Why would I be testing you? I’m just asking you for a favor. I need someone in the department to do it. I’m sure some of your colleagues would have objections. And you might, too, for all I know. And it goes without saying that you’re free to say no.”

“Am I?”

“Of course you are.”

“In that case,” Andret said, “I’ll say yes.”

—

HE WALKED HOME the next afternoon with a pamphlet sealed inside an envelope marked CLASSIFIED. They were simulation models. Secret ones. A bomber with limited ammunition engages a fighter that attacks with a single salvo of rockets. Game theory. He spent an evening reviewing the writings of von Neumann and Morgenstern, then set aside the Abendroth. This felt like taking off his boots after a long hike.

In his mind, he visualized the possibilities, then fractured them. For the pursued bomber he postulated the different scenarios: steady firing, intermittent firing, distant attack, close attack. To his great surprise the act of simulation brought him joy. He worked through until morning.

It was the kind of pleasure he’d not experienced since boyhood.

Two days later, in Hay’s office, he placed a dozen typed pages onto the desk. In the interim he’d hardly slept. Hay picked up the top sheet and ran his finger over the opening paragraph, reading it half aloud, the way he did when he was thinking.

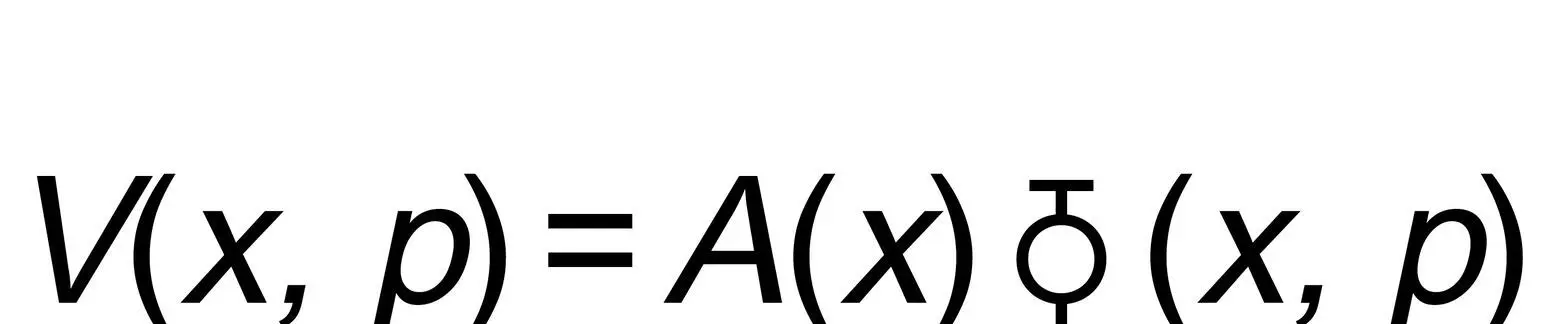

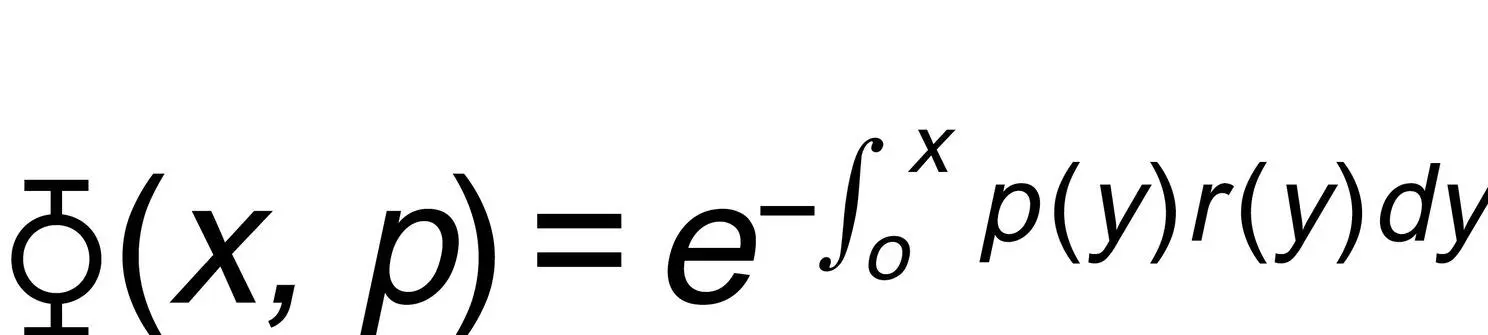

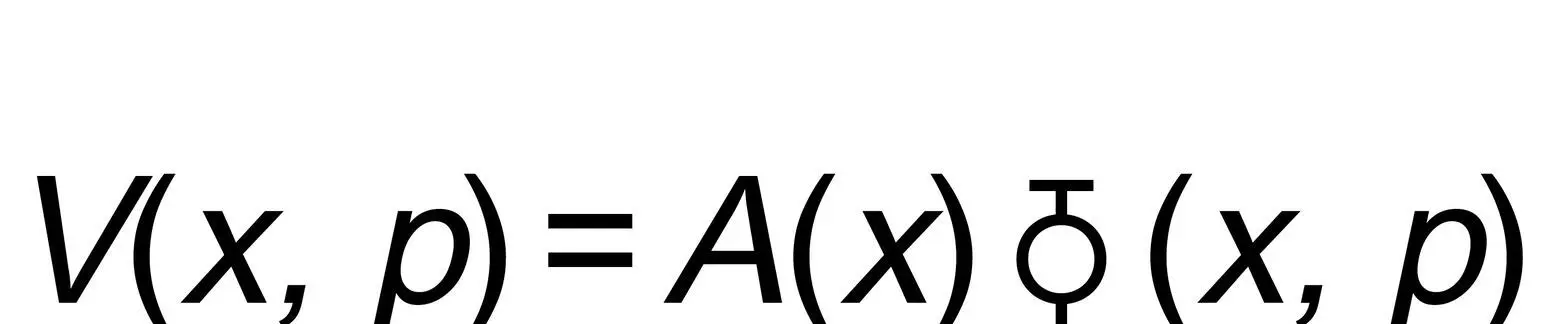

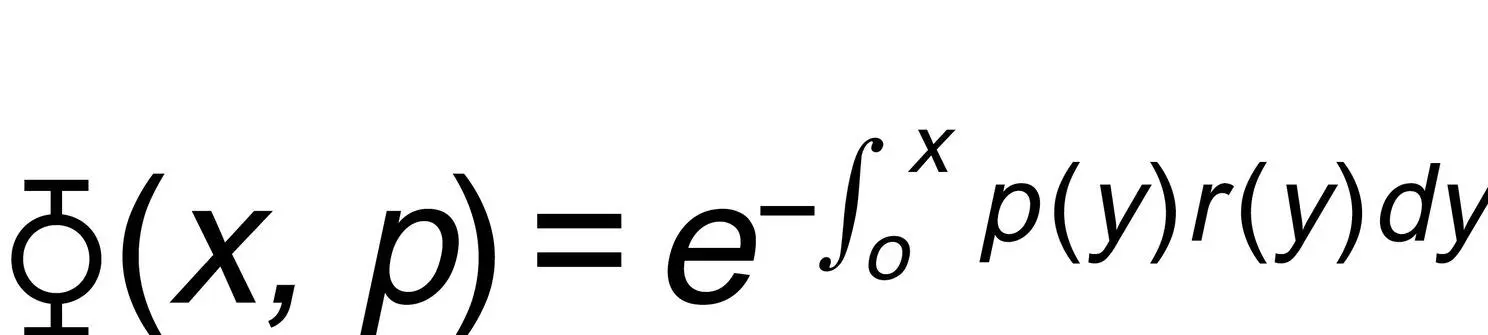

1. Preliminaries. The game considered has pay-off

where

The remainder he perused in silence. When he’d finished, he rose, walked to the cabinet, and poured two scotches, neat. “Thank you, Andret,” he said. “You did it.”

“Looks like I might have.”

“You look good, too, by the way. I haven’t seen you look this good in a while. Tired, naturally — but happy. You look like you’ve enjoyed something finally. Am I right?”

“Consider it a favor,” Andret replied.

Walking home that afternoon, though, he repeated Hay’s words in his mind. You’ve enjoyed something finally . He had, hadn’t he? For the first time in years, he’d enjoyed something in mathematics again.

—

IN THE SPRING, during a trip to Palo Alto, a reporter from The New York Times was sent his way. He was appearing in the Distinguished Lecture Series at Stanford, and she approached him after his talk. The Times, he noticed, liked to cover mathematics the way it covered state fairs or stock-car racing — as a wink to its readership. And it usually sent human-interest correspondents on the stories. But this reporter, a severe-looking young woman in a gray-striped pants suit, appeared to have been genuinely intrigued by what he’d said. She requested an interview.

Her name was Thelma Nastrum, and when she walked into the hotel bar that evening to ask him her questions, she didn’t look nearly as severe as she had at the lecture, nor quite as young. She’d changed out of the pants suit.

“A beautiful name,” he said as soon as the waiter had left. “Like a flower. A subtle, midwestern flower.”

“A fast-moving Scandinavian weed,” she answered. Out came her pad and pen, and she took a long swallow of her martini. “So,” she said. “What do mathematicians do all day?”

“Evidently that’s a popular query,” he answered. “What we do is think .”

She stirred her cocktail, then picked out the olive and sucked it into her mouth.

“And drink,” he added.

She made a note. “Imbibing,” she said. “While deriving.”

He liked her.

After a few minutes of questions, she asked if he thought he might possibly win the Nobel Prize for his work on the Malosz conjecture. She picked up her pad, smiled, and said, “I interviewed your colleague last fall. Yevgeny Detmeyer.”

Andret composed his face.

“When he won the Nobel,” she added.

“Yes, yes, I know. I’m well aware.” He signaled to the waiter again, pointing at their glasses. “There is no Nobel in mathematics,” he said, as tersely as Hans Borland might have uttered the words. He was irritated to realize he was already drunk. But he also wanted to salvage the evening.

“Oh, I didn’t know,” she answered. “Why not?”

“Some say because the lover of Alfred Nobel’s wife was a mathematician.”

“Ahh, yes — well, that would be a good enough explanation, wouldn’t it?” She made a note on her pad. “But certainly there’s an equivalent. What’s the most coveted prize in mathematics?”

“The Fields Medal.”

“Well, okay then — I’d imagine you’d have a good shot at the Fields Medal for your proof of the Malosz theorem. Do you think you’ll win it?”

“It’s not an unlikely proposition.”

“Ah,” she said, “a double negative.” The waiter arrived, and she launched impressively into another martini. When she raised the tetrahedral glass, it divided her smile into three.

“Indeed,” he said. “From a mathematician, however, a double negative is an acceptable proposition.”

“Two negatives make a positive, am I correct?”

Andret smiled. “You are indeed correct. At least for operations in which the identity element is one. ”

In her reporter’s pad she noted this as well. Then she excused herself to use the restroom. When she returned, her sweater was draped over her arm. He watched her hang it over the chairback. She was a few years older than he’d thought, but she was still in excellent shape.

Later, in the hotel room, she told him that she’d already been to bed with two Pulitzer Prize winners. “But never a Fields Medal,” she said.

He rose to freshen his glass. “I haven’t won it yet.”

“Well,” she said, “neither had they.”

—

THE PROBLEM STARTED, blinkingly, that fall. Walking to work one morning, he passed near a streetlamp whose cover had come unlatched. When he looked up, its bulb suddenly exploded into a halo of brightly flaming stars. He blinked. When he looked again, it was back to normal.

Later that day, he glanced out his office window and saw the fender of a bike do the same sort of thing. It transformed for a moment into a burning, multipointed polygon that flared and retracted. Then it was normal again.

—

“SIT DOWN, ANDRET.”

“No telephone again?”

“I’m afraid not,” said Hay. “Not for what I need to speak with you about this time, my friend.”

Читать дальше