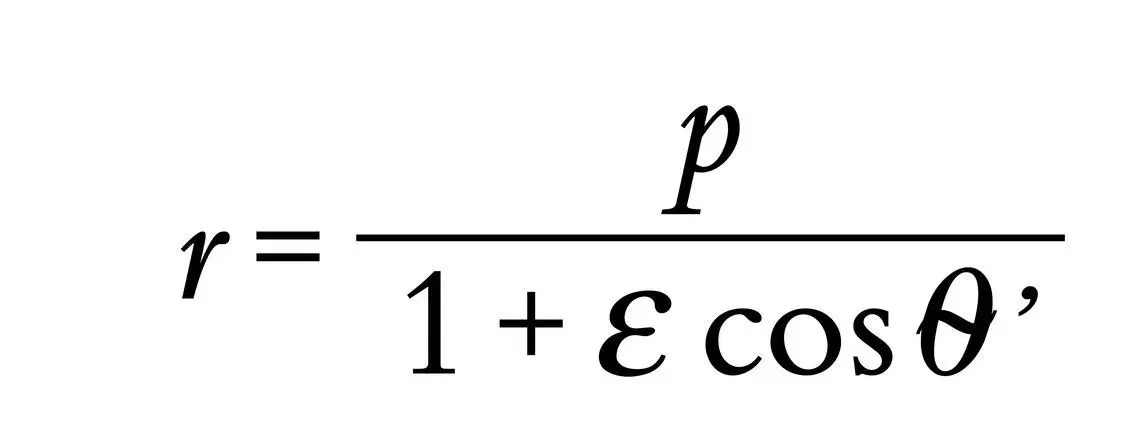

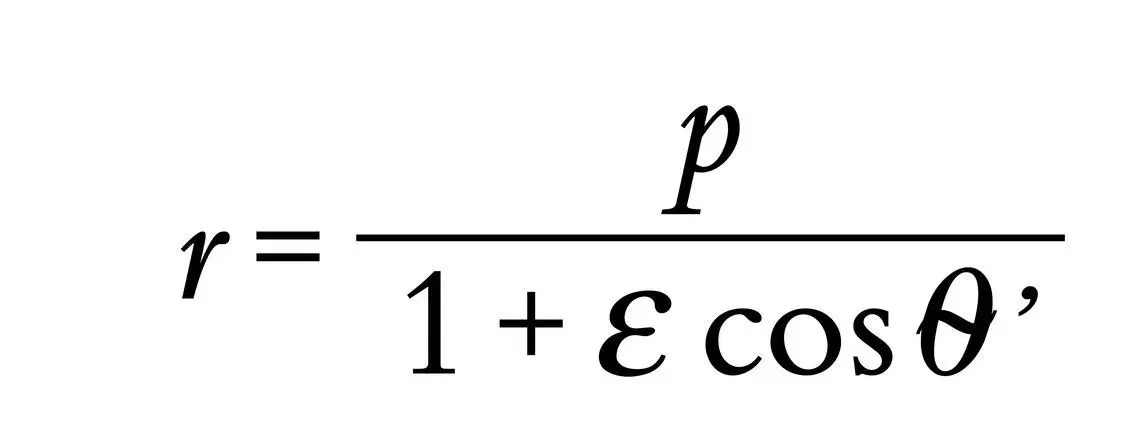

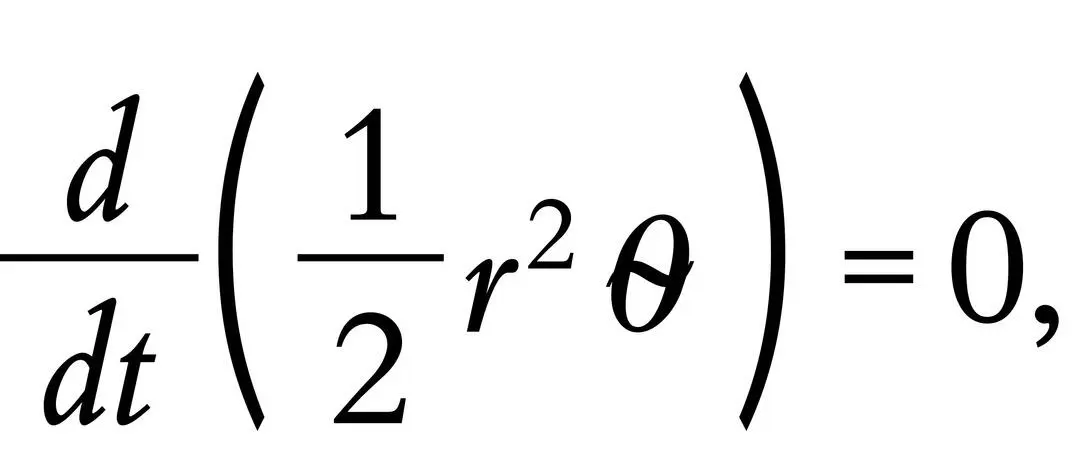

Underneath this:

2. A line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

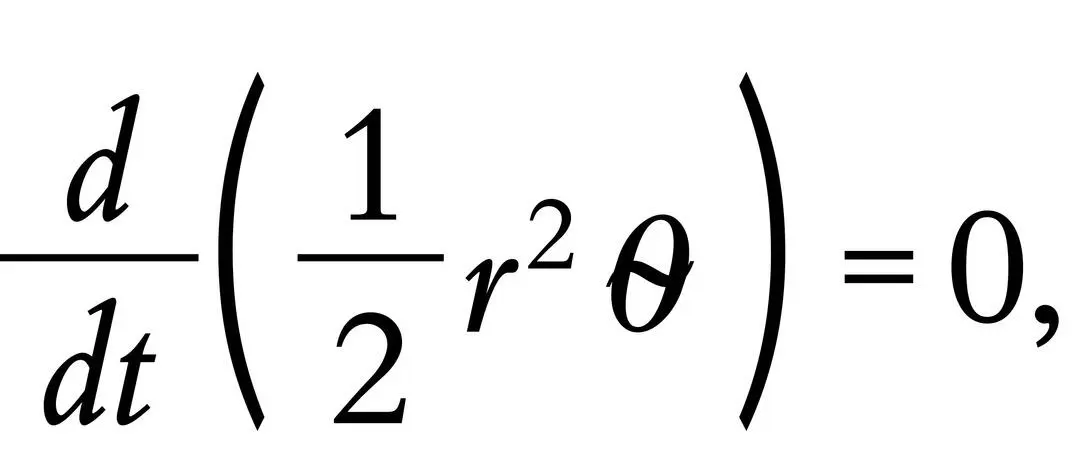

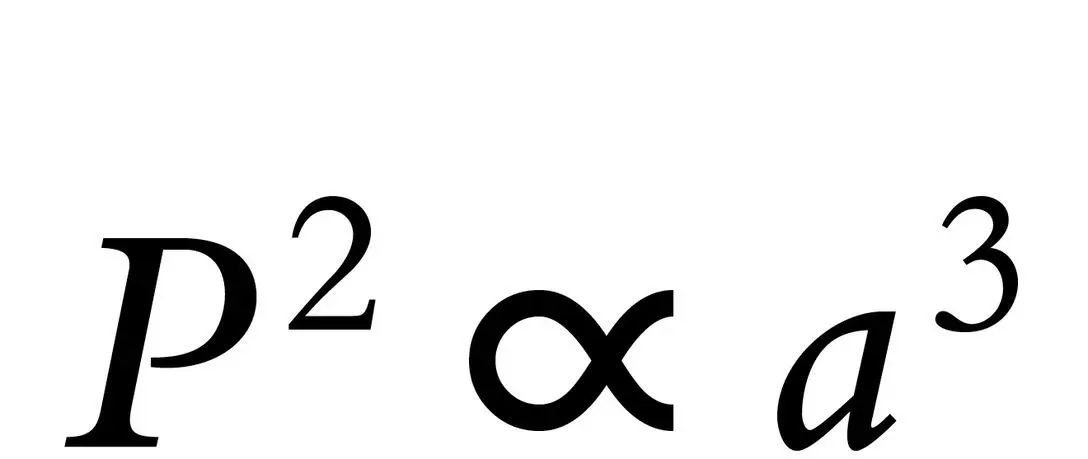

And, below this:

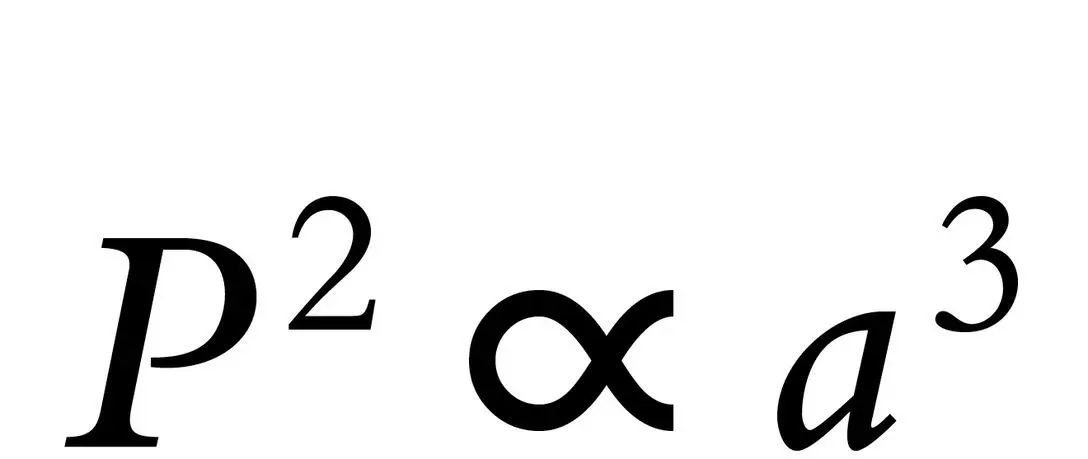

3. The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

There they were, summoned by nothing but his own devotion. The Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae. Working blindly, he’d rederived what the great Johannes Kepler had first deduced three and a half centuries before.

The laws of planetary motion.

—

WHEN HE ARRIVED at his teaching sections the following Monday, his students were already reading the article. The front page of the Daily Cal . He’d had no warning. The illustration was the famous seventeenth-century portrait of Kepler himself, a simultaneous artistic study, Milo had always thought, of both malleability and relentlessness. The byline leapt from the page.

Cle had said nothing about it.

All day, people greeted him. Professors. Other graduate students.

That evening, Hans Borland reached across the desk with the decanter. “Dry sherry?”

“Please,” Milo responded, pulling a glass from the row and sliding it across. “Might as well celebrate.” Then, an unmitigated lie: “I’ve been making progress on the dissertation.”

Borland fiddled with his cuff link. “Progress?”

“Yes.”

“That’s funny. Because I read today that you’re wasting your time.”

“Well—”

“With your antique sextant.”

“It’s a quatrant, Professor. Derived from a mariner’s sextant, yes.”

“I know what a quatrant is, Andret.” He looked stonily across the blotter. “It’s a fool’s stab at attention. What’s it got to do with the Malosz conjecture?”

“It’s a hobby, sir. I became interested in the work of Tycho Brahe.”

Borland’s expression froze. “The Borland invariant,” he said. “I was eighteen years old when I came up with it. And not even a month after my birthday, are you aware of that? I was at Caltech, already doing graduate work.” He glanced over. “And a year after that, I was on faculty.”

“As you know, Professor, I got a late start.” A pathetic remark.

Borland ignored it. “Tycho Brahe”—he reached for a stack of folders—“Tycho Brahe thought the earth was the center of the solar system.”

“He was a genius.”

“He was no genius at all, Andret. He got it wrong.”

“Nobody gets it entirely right.”

“Pardon?”

“Or almost nobody. Kepler, maybe.”

“Listen to me, Andret. Stop talking nonsense. It’s the excuse of the lame, and it’s fouling this campus. It’s fouling this whole country of yours, for that matter. You are not lame, Andret. Do you hear?”

“I try not to be, anyway.”

“Poppycock, Andret. Listen to me. Are you listening to me?”

Borland seemed to actually be waiting for an answer.

“Yes, I am,” said Milo.

“You have to go against the times. You have to always go against the times. Do you know what that means? What do you think Kepler was doing? What do you think Galileo was doing? It is where discovery comes from, Andret. Not from going this way and that with the crowd.”

“Yes, I know, but—”

“Now get back to work. All you’ve done is rederive an ancient calculation. You have a talent and you have a discipline, and I can see that you’re wasting both.” He dropped the folders back onto the desk. “Don’t make me wonder if we’ve made a mistake with you.”

—

“WELL,” SHE SAID. “Did you like the article?”

It had been days. He’d been at work, trying to change things. “You’re with Biettermann,” he said without looking up.

“What?”

Now he lifted his head.

She exhaled smoke. “And what if I am?”

“Well, for one, you could have told me.”

She lit another cigarette. “Stop acting like a bourgeois.”

“There’s nothing bourgeois about it.”

“Stop caring about your parents’ morality, Andret. You’re above that.”

He looked away. It was unclear if she even knew about what he’d done. He still couldn’t remember the girl’s name.

“And stop being so ugly,” she said.

“Thank you. Glad to know what you think.”

“Andret, do you really want to hear what I think?”

“No.”

“I think you’re incredible.”

“Bullshit.”

She looked into the distance. “I want to save you,” she said. “I think that’s what it is. Save you from your own brilliance.” She tapped out another cigarette. “Or maybe for it.”

“What?”

“You heard me.”

“I don’t need to be saved, Cle. That’s ridiculous.”

—

AWAKE NOW FOR almost two full days, scribbling notes into the tiny cardboard pad that he’d been carrying since the meeting with Borland. To meals. To class. To every single place he went. He’d made his way deeper into the problem. Walking alone along the water one evening, he watched the cargo ships creeping south beneath the bridge. Tiny blinking cities of light on the water. Starry bottles drifting sideways in the black. Incredibly, this was where he’d stumbled upon a crack. A narrow one. A thought had reached back. Encasing sheens. Volumeless shapes. He sent his mind deliberately away, then allowed it back. The crack remained. It was real.

The Malosz was not insurmountable. It could be solved in the higher dimensions.

This is where the answer first made itself known to him, in the muddy-smelling dark on a garbage-strewn dock above the tidal flats in Emeryville. Tinge of rot in the air. Wintertime headlights streaming ceaselessly from the west, dividing north and south at the shore. Complex white curves incising themselves against a black-paper rendering of the world. The trudging ships below. It would be provable in another dimension. This was the route. His rivals would never think of it because it was so deeply counterintuitive. But the more he considered it, the more clearly he knew — this path would be orders of magnitude simpler.

He’d found it.

From a tar-soaked piling, he flicked his cigarette into the smelly sand. Pinched a drink from the flask in his back pocket and headed home to sleep.

—

“EARL AND I are mortals,” she said.

A doughnut store this time. Shattuck Avenue.

“Bullshit.”

“Mortals hang out with mortals, Andret. Do mortal things.”

“Bullshit, Cle.”

“We talk. We walk. Sometimes we trip. We don’t bother with conundrums the human mind has never breached.”

“You’re sleeping with him.”

“Maybe I am.”

“What? Cle?”

“I said maybe I am.”

“I’m begging you.”

“Don’t beg.”

“Please, Cle.”

“I said don’t.”

“Then fuck you.”

“Brilliant. Thank you.” She looked out the yellowed window, dragged on her cigarette. “If you want to fuck me, you know, you still can. Anytime you want.” The smoke lingered. “You can always do that.”

“Thanks.”

Silence.

“You don’t think I know what you did, Andret?”

“I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be. It doesn’t matter.”

“Yes, it does. I’m sorry.” He’d been waiting to say it. “I’m sorry, Cle.”

Читать дальше