‘It’s nice,’ I said. I lay down next to him and pretended to enjoy the sun, which was making me sweat.

‘This is great,’ I said. ‘Do you mind …?’

He lay on his back with his eyes closed. ‘Mind what?’

I took off my shirt. He opened his eyes, blinked, looked at me again. Smiled. ‘Hell,’ he said. ‘Why not? It’s not fair, the way women always have to wear tops.’ He closed his eyes again.

I lay next to him, no more exposed in my taupe satin bra than I’d be in a bathing suit. I moved my arm so that it brushed his.

Still nothing. He moved his arm away and smiled at the sun. I moved my arm again. He moved his. I moved my leg until our thighs touched. This time he shifted a little uneasily. Of course I should have left things there, moved away, pretended disinterest. Given up. I rolled over heavily and kissed him, my unclothed chest mashed against his.

He threw me off as if I were a rabid dog. He pushed me off, sat up, rose to his knees. ‘Jesus, Grace,’ he said. ‘What the hell? You’re married. To Walter .’

I kneeled next to him, a sharp stone pressed into my shin. ‘Forget that,’ I said. ‘Forget Walter.’ As if either of us could. I reached out and rested my arm on his shoulder. ‘Don’t you want me?’ I said.

His mouth opened and closed and he flushed dark red. He shrugged off my hand and stood up. ‘Let’s just forget this whole thing happened,’ he said. ‘Okay?’ His voice quivered with his effort to stay calm. ‘Let’s just get back to work. We don’t want to wreck this project.’

But of course I did. I wanted to wreck this project, wreck him and Walter, tear apart this life I found myself floundering in. I was so humiliated and disappointed that I started crying. Hank looked at me for a minute and then grabbed his shirt and ran down the rocky path. He left me alone, hot and sweaty and half-naked, brokenhearted, and that’s how Walter found me an hour later when he passed by with his gill net and happened to hear me crying.

‘Hello?’ Walter called from below me. ‘Who’s up there? Are you all right?’

I couldn’t answer; I couldn’t stop crying. Walter left his gill net by the transects and sprinted up the slope.

‘Grace?’ he said. He kneeled down beside me and wrapped me in his arms. ‘Grace?’ he repeated, completely bewildered. ‘What is it? Are you all right?’ He checked me quickly for cuts and bruises, his hands pausing over the sweat and dirt and gravel stuck to my back. His face darkened. ‘Did someone …?’ he asked. ‘Has anyone …?’

‘Hank!’ I wailed. Perhaps I meant Walter to understand that the only way he could. Perhaps that cry simply tore itself from my heart.

‘Hank?’ he whispered. ‘Hank did this?’

I never contradicted him. I let him dress me, lead me back to the car, think what he wanted. I let his own heart break, half with rage at my supposed violation, half with a pain he could never admit, and I didn’t care. I knew I could never face Hank again, never survive unless Hank was out of my life. I could never stand to watch Hank and Walter together. I brought our world crashing down around us, the end of another life.

A Refuse Heap

No one could have missed the changes that occurred in Walter after that. Over the years, five horizontal lines had carved themselves across his forehead, which folded into neat corrugations when he lifted his eyebrows. Now a pair of vertical lines sprang up above his nose, crossing the horizontals in a ragged checkerboard. The web of fine diagonals around his eyes darkened and deepened, and two furrows cut from the wings of his nose to his mouth. His face cracked into a complex map, as if I’d carved it with a razor; and at night, when he thought I was sleeping, he groaned. Not once or twice, on falling asleep or awakening, but all night long. Each time he rolled or moved he let out a low, broken sound, as unforced and unstoppable as breath. In the mornings he lay in the tub, quite defeated, and he couldn’t get out until I’d brought him coffee. Through all this he could never say what was hurting him so: as if, by his not saying, I wouldn’t know.

I knew. Walter had confronted Hank and Hank had refused to defend himself; all he’d ever said to Walter was, ‘I didn’t touch her.’ Walter turned all his frustration and hurt into anger and cut Hank off completely, and still it wasn’t enough for me. I was seized with a sense that I’d lived my whole life wrongly, falsely, badly; and all I could think of to do was to thrash at the world around me. Walter’s project collapsed and his group disbanded and Hank transferred to Page’s lab, and I congratulated myself on how well I’d punished everyone, even me: Walter was perfectly kind and sympathetic, but he could no longer make love to me. Perhaps he knew more of the truth than he knew he did.

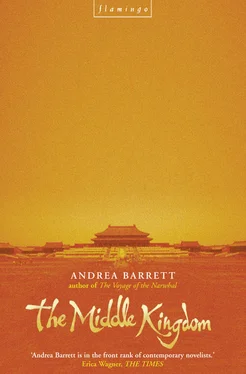

As the fall wore on, Walter threw himself into the plans for an international conference he’d been invited to organize in Beijing, for the following September. He grew tired and anxious, drowning in a sea of visas and invitations, travel agents and hotel brochures, but I couldn’t make myself help him or even show any enthusiasm for the trip. This was my chance to follow in Uncle Owen’s footsteps and see what he had seen, but I had never meant to go like this: a forced march on the arm of an angry husband, who refused to allow me to stay at home alone. Our living room filled with papers and abstracts and I grew guiltier each day, until finally I roused myself enough to write Dalton and tell him some of what was happening. I described Hank and what had happened in the swamp, and what I had done to Walter; ‘… and now he wants me to go to China with him,’ I finished. ‘What am I supposed to do?’

‘Whatever you have to,’ Dalton wrote back. ‘But just go.’

His note lay on top of a big box of Uncle Owen’s things, all his diaries and dictionaries and maps, and despite myself the box roused my interest a bit. I compared Uncle Owen’s things with the guidebooks Walter brought home, and even that brief acquaintance was enough to tell me that the China Uncle Owen had visited was gone. The walls around Beijing had vanished; broad streets cut through the old alleys; concrete towers had replaced the low houses. Even the language was different: Beijing, not Peking. Cixi rather than Tzu Hsi.

I tried to take an interest in that. I buried the knowledge of what I had done, I buried everything, and I tried to forget Hank and to warm toward Walter, to show a little enthusiasm for this trip he was working on so hard. I tried to believe we might enjoy traveling together; we had in the past. But meanwhile I had nothing to do but eat.

When my mother visited early in December, she turned white with horror at the sight of me. She turned white and then laughed and then frowned and then smiled, and then she tore a sheet of paper from a pad and started outlining a diet. Slim as always, she wore a straight navy skirt and a white blouse with a boat neck, beneath which her bra straps showed. For my birthday, she’d brought me two bras that resembled armor, boned and thick-sided and fastened with long rows of hooks and eyes, as expensive as a good pair of shoes. Neither of them fit.

‘Grapefruit,’ she said firmly. ‘Grapefruit after every meal — burns up the calories. High protein, no fat, no carbohydrates, ten glasses of water a day — how did you let this happen? ’

I looked at the floor. Letting had nothing to do with it — I had done it on purpose, eating with all the stealth and steadiness of a prisoner of war. Since my escapade in the swamp, I’d gorged as I hadn’t done since Mumu’s death, gaining ten pounds, fifteen, twenty. At twenty, Walter had noticed. We ate our meals in silence then, he reading scientific journals while I flipped through Uncle Owen’s China diaries, searching for solutions to my life. Walter had frowned at me one night, after I’d taken a second helping of mashed potatoes and then a third.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу