Getting from his bedroom to the front door was easy. There was no one about — his father and his sister were still in their bedrooms — and he reached the front door in a soft-stepping dash. Getting to the gate was easier. He sprinted across the yard, shoe heels smacking the concrete. He breathed a sigh as the gate swung closed behind him, and then reached into his trouser pocket for his BlackBerry to check the time, but his pocket was empty, he had left the phone behind. He hesitated a moment, and then, with a brusque shake of his head, he stuck his plastic folder under his arm and set off at a trot for his job interview.

The first person Furo met was the stocky Adamawa man who had the monopoly on garbage collection in the quarter of Egbeda where Furo lived. He was pushing his garbage cart down Furo’s street, and he drummed the cart’s side with a hooked metal rod to announce his presence to the gated houses. But on catching sight of Furo, the rod slipped from his grasp and dangled on a string from the cart’s handle, and then he averted his gaze to the shambles in the cart’s bed, but kept on advancing, his steps growing slower, the cart trundling before him with its bold stench. Furo usually delivered the house garbage to him, and they had bantered several times over the haphazard costing of his seller’s market service, so Furo, out of habit, greeted him as they drew abreast, and at once regretted the appearance of his voice. The man’s silence only sharpened the bite of Furo’s blunder. They pulled past each other, and Furo reached the bend in the road before casting back a nervous, salt-pillar look. The cart was abandoned in the middle of the street, and the man stood several paces in front of it, one hand shading his eyes and the other slapping at blowflies, and stared at Furo with festering intensity.

On the next street Furo approached the Isoko woman who ran a buka in front of a tenement building for navy personnel and their families. She was frying hunks of pork in a cauldron of seething oil that straddled a coal fire. Her naked toddler — a girl, her round tight belly accentuated by strings of coloured plastic beads looped around her waist — sat on the ground a short distance from the fire. The child played with fistfuls of charred wood chippings and coconut shell; she babbled to herself — or her imaginary friend — through popping bubbles of spit. As Furo drew near, she looked up with fat-cheeked wonder and caught her breath. He was expecting it, but when the howl came it startled him nonetheless. Hearing the rush of the mother’s footsteps, he glanced around to see her picking up the child, and after turning back, he heard her say with a laugh, ‘No fear, no cry again, my pikin. No be ojuju, nah oyibo man.’

And so it went: stares followed him everywhere. Pedestrians stopped and stared, or stared as they walked. Motorists slowed their cars and stared, and on occasion honked their horns to draw his face so they could stare into it. School-bound children hushed their mates and poked their fingers in his direction, wrapper-clad women paused in their front-yard duties and gazed after him, and stick-chewing men leaned over balcony railings to peer down at him. As he passed by the corner store where his mother got her emergency groceries, a hubbub of voices burst out, and when he looked over he saw the attendants, Peace, Tope and Eze, crowded in the doorway, gawping at him. A radio jingle — Mortein! Kills insects dead! — blared from the barbershop where he got a shave every weekend and his hair cut every month, and when he hurried past the front, Osaze, the Bini barber, who was bent over a smouldering pile of hair, froze in that position, only his head moving through thickening smoke as he followed Furo with his eyes.

No one had called out his name. He’d passed houses he wasn’t a stranger to, and he’d been stared at by several people he knew, people whom he had lived beside for many years, joked with, been rude to, borrowed money from — and yet no one had recognised him.

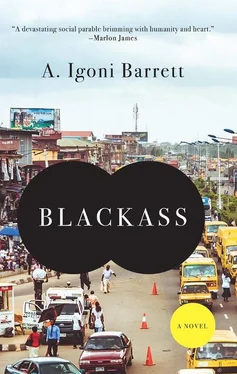

Lagos, they say, is a city of twenty million people. Certainly no less than fifteen million. The economic capital of Nigeria and its most cosmopolitan city, Lagos hosts the highest numbers of foreigners in the country. Construction workers from China mainly; restaurateurs, hoteliers and import dealers from India and the Middle East; tailors, drivers, domestics and technicians from West and Central Africa; expat employees of Western multinationals and global bureaucracies; sojourning journalists and religious crusaders; few exchange scholars; fewer tourists. In some parts of the city it is not unusual to see a white person walking the streets on a sunny day. Ikoyi, Victoria Island, and Lekki Peninsula. That’s where oyibos — light-skinned people — live, work, play, and are buried. In private cemeteries. In Apapa, Oshodi, Ikeja, and other business districts of Lagos, the sight of a white man passing through in a chauffeured car is by no means a rarity. But if in traffic his car were bumped by another motorist and he came down to demand insurance details, it is likely that a Lagos-sized crowd would gather to stare, drawn by this curious display of courage. As for the outlying — economically as well as geographically — areas of Lagos, places such as Agege, Egbeda, Ikorodu: a good number of the inhabitants of these neighbourhoods have never held a conversation with an oyibo, never considered white people as anything more or less than historical opportunists or gullible victims, never seen red hair, green eyes, or pink nipples except on screen and on paper. And so an oyibo strolling down their street is an incidence of some thrill. Not quite the excitement decibels of seeing a celebrity, but close.

One anxious step after another and Furo finally reached the stretch of roadside marked out by collective memory — the script on the metal signpost had since rusted away — as Egbeda Bus Stop. It was mid-June, the flood-bearing rains had arrived, and the road drainage, which was clogged with market litter, was undergoing expansion by the municipal authorities. Half of the sidewalk was dug up, the excavated soil heaped on the other half, and these hillocks of red mud had been colonised for commerce, turned into a stage for stalls, kiosks, display cases, impromptu drama. In this roadside market stood food sellers with huge pots of steaming food, fish sellers with open basins of live catfish and dead crayfish, hawkers with wooden trays of factory-line snacks, iceboxes of mineral sodas, and armloads of pirated music CDs, Nollywood VCDs, telenovela DVDs. Then there was the noise, the raw sound of money, of haggling and wheedling and haranguing, the rise and rise of voices against the roar of traffic. The bus stop was crowded with heads and limbs in a swirl of motion, and jostling for space on the motorway were all types of vehicles, from rusted pushcarts to candy-coloured mopeds to sauropod-sized freight trucks, all of them vying with pedestrians for right of way.

Lone white face in a sea of black, Furo learned fast. To walk with his shoulders up and his steps steady. To keep his gaze lowered and his face blank. To ignore the fixed stares, the pointed whispers, the blatant curiosity. And he learnt how it felt to be seen as a freak: exposed to wonder, invisible to comprehension.

About two hours into his trek, just as he sighted in the skyline the straggly multi-storey buildings of Computer Village, Furo realised he had misjudged the distance. His interview was at Kudirat Abiola Way, on the other side of Ikeja, at least an hour’s walk from Computer Village. A long way still to go. His face smarted from the sun’s heat, the underarms of his shirt were moist with sweat, and thinking of the road he had to cover, he pulled out his handkerchief and scrubbed his face. The cambric came away browned with grime. He fisted the handkerchief into a wad, adjusted the folder under his arm, and quickened his pace. He hadn’t come this far to be defeated. This was the time to find a solution. But first he had to find out the time.

Читать дальше