He arrived at The Palms with ninety naira in his pocket.

Who did Furo see but a white person striding towards him as he passed through the glass doors of The Palms. A long-haired woman with a large mole on her chin, she wore a lavender summer dress and green oversized Crocs. In both hands she grasped the big yellow bags that boasted of lowest prices. Faced with this test, this face-to-face with a white person, Furo realised he was unprepared for the encounter. He was worried how they would see him. Could they tell by sight that there was something wrong with him? If they could, then why, how, what was it they saw that black people couldn’t? Thinking these thoughts, Furo halted in front of the glass doors, his attention fixed on the woman. She drew close, her gaze flicked over his face, and then she was past, her Crocs clopping and ShopRite bags rustling.

The woman’s lack of reaction to his presence proved nothing, Furo told himself, but he feared that before long he would find out the truth, because in the crowded passage ahead of him were several oyibo people, some Indian- and Lebanese-looking, some Chinese, walking alone or in small groups, laughing, chatting, gesturing at the bright lights in storefront windows: all of them as indifferent to their difference as he wasn’t to his. Then he thought he had stood too long in the same spot, that people must be staring at him and wondering, and he looked around but caught no eyes, they seemed to ignore him in the midst of plenty. Buoyed by this glimmer of a chance at a normal life — one where he wouldn’t always be the cobra in this charmless show of reality, the centre of attention — he started forwards into the chill of the mall.

Furo’s fear came to nothing, as none of the oyibo who looked at him gave the impression that he was something he shouldn’t be. The few glances he attracted came from his own people, and even they seemed more interested in his dusty shoes, his wrinkled trousers, his sweat-grimed shirt, his cheap plastic folder, all the signs showing he wasn’t kosher in the money department. That was a look he was used to from before, and so it didn’t worry him. Better the scorn he knew than the admiration he didn’t. But above all, better the people who ignored him than the ones who didn’t. Moving through the crowd, he began to feel more at ease with the approach of non-blacks. There was no uncertainty about their reaction to sighting him. They would see him and maintain stride, see him and keep on talking, see him and show no surprise, every single time. With the others, the majority, it was hit-and-miss. And after some near misses, a woman hit on him.

He was almost at the entrance of the lavatory when he heard a hiss behind him. He spun around to find her standing there. Though he had never seen her before, he recognised her at once. She was one of those youngish women who dressed not so much to kill but rather to mimic teenagers — which sometimes they claimed they were, rarely truthfully — and spent their days stalking the mall in a hunt for lone white men. In two words, she was a runs girl. In one, a prostitute. She had the worn-out sensuality, the overbearing perfume, and the arsenal of glances. While her mouth said, ‘Hello there,’ her eyes were busy telling Furo, I’ll be good to you, baby. Or something to that effect. Perhaps, on some other day, he might have responded to the promise in her eyes, but today he didn’t even reply to her greeting before whipping back around and striding away from the lavatory.

He arrived at the food court to find it brimming with voices. After-work hours on weekdays were busy periods for The Palms, as commuters killed time there — eating dinner, watching movies, browsing the shops — in a bid to wait out the worst of the traffic. Looking around for somewhere to sit, he saw that most of the tables were occupied by whispering couples or chattering groups of office colleagues, but near the centre of the dining area stood a table with three empty chairs, the fourth taken by a man reading a book. Weaving a path through the jumble of conversations, Furo approached the silent table, and the man raised his head. His dreadlocked hair was neck-length, and his beard stubble was sprinkled with grey, as was the hair on his chest, which showed through the V-neck of his T-shirt. Despite the greying, he was about Furo’s age.

‘Hello,’ Furo said. ‘Can I share this table with you?’

‘Please,’ the man replied, and waited until Furo sat before returning to his book.

After placing his folder on the table, Furo raised both hands to massage his neck, at the same time throwing a look of resentment at all the happy people seated about him. He envied them. Unlike him, they all had homes to return to. He knew that the food court and all the shops in the mall would be closed by ten, and the mall would be emptied of people and locked up after the cinema upstairs finished its last showing around midnight. And then where would he go? He couldn’t risk illness, not when he had no money, and spending another night in an abandoned building full of mosquitoes seemed to beg for malaria. But what choice did he have today, tomorrow, the day after, until he began work at Haba! in a couple of weeks? In an effort to get away from these insoluble worries, Furo returned his gaze to the table, and narrowed his eyes at the book across from him. Fela: This Bitch of a Life — the words on the front cover. The man’s short-nailed hands gripped the book cover, pinning it open. Head cocked to one side, eyelids lowered, face expressionless, his lips moved silently as he read.

This bitch of a life indeed , Furo thought. There he was, living his life, and then this shit happened to him. He had always thought that white people had it easier, in this country anyway, where it seemed that everyone treated them as special, but after everything that he had gone through since yesterday, he wasn’t so sure any more. Everything conspired to make him stand out. This whiteness that separated him from everyone he knew. His nose smarting from the sun. His hands covered with reddened spots, as if mosquito bites were something serious. People pointing at him, staring all the time, shouting “oyibo” at every corner.

And yet his whiteness had landed him a job.

Furo blew out his cheeks in a sigh. Dropping his hands to grasp the table, he pulled in his chair. The metal legs screaked on the floor tiles. At this sound his tablemate looked up, and Furo, seizing the chance, said to him, ‘Sorry to bother you, but can you please tell me the time?’ The man nodded yes, put down the book, reached into his trouser pocket, and pulled out a phone. He said, ‘It’s almost five thirty,’ to which Furo responded, ‘Thanks.’ As the man returned the phone to his pocket, Furo said, ‘Funny how time drags.’

‘When you’re bored,’ the man said. He smiled and added: ‘And when you’re waiting.’

Furo forced a laugh. ‘Also when you’re in trouble.’

‘That too,’ the man agreed. He waited a beat. ‘Do you mind saying what the trouble is?’

‘Ah … no,’ Furo said. ‘It’s not something I can talk about. But thanks for asking.’

The man leaned forwards in his chair and crossed his hands over his book. ‘But we can talk if you want. To pass the time.’ He tapped the book. ‘That’s one good thing about books. You can always pick up from where you left off.’

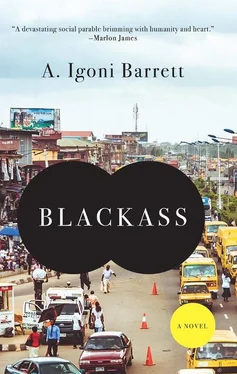

‘I have to confess I’m not a big fan of books myself,’ Furo said. He thought a moment, and then chuckled. ‘I shouldn’t say that in public. I just got a job selling books.’

‘What sort of books?’

With a glance at the man’s shock of hair, Furo said: ‘Probably not your type. Business books, that’s what the company sells.’

‘What’s the company’s name?’ As Furo hesitated, the man said, ‘I ask because I used to work for a publishing house. I might know your company.’

Читать дальше