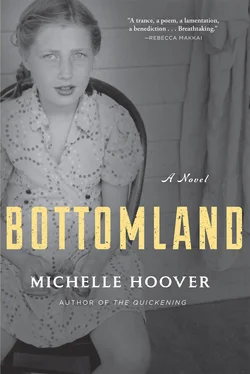

Michelle Hoover

Bottomland

To my late father, Lee, my Aunt Irene,

and their mother, Bess,

the first to speak in these pages,

and whom I never had the chance to meet

Don’t forget me, don’t forget that hill

the horses cantered you down

to the bottom land.

From this stone, ageless heart,

remember your mother,

a mother who loved her children.

— Margo Taft Stever, “Bottom Land”

Part I: Never Make Too Much

It was little more than a month before winter shut us in when I last saw the youngest of my sisters. Our little Myrle. I woke to find her shivering just inside the front door when she should have long gone to bed. It was dark as a cellar in that hall and outside it would be darker — miles of field and grassland lay beyond the front porch. Our house sat alone on the prairie, far from its neighbors. The road to our place was a run of stubble and dirt. Myrle’s hair shone white on her shoulders and she wore nothing but a nightgown, her arms and feet bare in the cold — not enough sense to cover herself though she was almost grown.

I raised my lantern to her face. “Why, Myrle,” I said, “you’ll catch your death.”

The look she gave, as if startled out of sleep. Her eyes teared and she ducked her head. The door was locked at her back. After the war, Father would have made sure of it. A draft rushed our ankles from the doorstep. The rest of the house was still, nothing but a wind outside knocking the stable gate. I touched Myrle’s forehead and felt it damp. She brushed away my hand. Her other hand she hid behind her hip, and when I asked her to show it, she glanced up the staircase and called our sister’s name, as if Esther might rush down to save her. I turned my head and Myrle was off — the white of her nightgown a whirl up the stair. In their bedroom above, the two girls whispered together. When at last Esther stepped out, she looked down at me with her dark face, her hands very still where they gripped the rail. Without a word, she slipped back inside and drew the door shut behind her.

Later that night, I would wake again and remember Myrle as she stood in the hall. What noise had woken me a second time, I could not say. The hall had been cold when I’d found her, though her fingertips were colder. Her nightgown carried the smell of the riverbed. As she rushed away, I saw how her hair clung to her neck, her nightgown damp against her back, and the mat where she’d stood was dark with wet. When Myrle was born, I too was just a teenager, but when first I held her, I believed nothing was so fearsome and astonishing as a child. All the many times we had watched her and chased her and held her fast — brushing her hair, tickling her feet, clutching her hands. As I lay in my room, I imagined again the heat of the flame as I’d held up my lantern. I saw how it had burned close to Myrle’s cheeks until she flushed. I took the blanket from my bed, wrapped it around my shoulders, and stepped out into the hall. When I tried the front door, it was locked as it had been, but the hall was empty now. Not a sound came from the room above.

I should have been wary of the stillness the next morning, but quiet in a house is a thing a woman likes to keep. The sun hadn’t yet risen. A sliver showed against the eastern windows, and I sat on the kitchen steps, waiting for the others to wake. Through the fog, my brothers walked in the dark with their buckets of milk. Lee, the younger, was large as an oak and pale, while my older brother Ray was thin, bent. A tin cup banged from his hip, one he hooked to his belt to keep only for himself. They dropped the buckets by the steps and Ray grimaced, wrenching the door open with his good hand. “You’re late,” I told them. Lee shrugged, following his brother inside. “There’s eggs,” I called. The buckets smelled of hay, the milk adrift with dirt and hair until I strained it, though I couldn’t convince myself to even start. I thought of frost, of the snow coming. We had the last of the harvest to bring in and the cellar to fill with canning, a new washhouse to frame if my brothers could get the lumber for a good price. Were Mother alive, she would have liked to see such a thing done. The door banged open at my back and Ray hurried off without another word between us. Lee stopped to nudge me with the toe of his boot. “Ray’s in a mood.”

“Ray’s always in a mood.”

“Right, right,” Lee said with a wink. He put a knuckle to his ear. “Esther didn’t come out this morning.”

“She must be in the pastures.”

“She said she’d come to the smithy, said she had something for me. Don’t forget, she said. And I almost did. She forgot more, I guess.”

Lee headed off and I opened the door to the kitchen. Esther, she didn’t forget anything. Inside, my sister Agnes stood over the stove, picking through the pan of eggs. I might have scolded her, but the kitchen table was empty, the chairs pushed close. I had left a stack of plates by the sink for our breakfasts. Half of them were stacked just the same, clean enough they shone. The sun was starting now at the horizon, and Agnes still wore her nightgown.

“Why aren’t you dressed?”

Agnes’ curls were matted from her sleep on the back porch, her refuge from her sisters in the warmer months. She looked like a child standing there, balancing on her toes. “I couldn’t. Our room is locked.”

“It must be stuck again. Are you sure?”

She pinched her gown to show me what I had already seen.

“Where are your sisters?”

“I don’t know,” she complained. “They’re sleeping.”

I hurried to the foot of the stair, but the door at the top was closed. “Esther, Myrle,” I called.

Agnes joined me in the hall with her plate.

“At the table, Agnes.”

She made a face.

“Go on up, then,” I said. “Wake them.”

“But the door.”

“Push harder .”

I went myself into the chill morning. Without the two girls at their chores, a half dozen of our youngest steers would be out to pasture, their feed low, and both my brothers were off without knowing. Already the animals in the barn were restless, begging for attention. The potatoes in the garden were close to a freeze, three dozen or more tomato plants set to move to the cellar. In the distance, the Clarks’ chimney smoked, the glint of a lantern in the Elliots’ barn. I drove the cows from the pasture, my arms heavy with buckets by the time I returned from the well. In their pen, the hogs clamored for feed, and I carried a pail of swill to them and turned the horses out into the growing warmth.

Back in the house, the door at the top of the stairs was closed. When I put my ear to the wood, I heard nothing. When I tried the knob, it wouldn’t turn. My baby sisters were huddled together in their beds, or so I imagined, and I felt old and dry and ever less a woman as my years went and I remained unchanged, except for the fraying of my hems. With Mother gone, I had tried my best, but our youngest were growing wild. They freed the animals from their pens, filled their pockets at the market without paying. For a month, Myrle had gone to bed without supper and in a teary state, and Esther had taken to spying at us from around corners, that mushroom cap of her hair short above her ears, like a boy’s. Aren’t you too old for games? I asked her. Aren’t you too old? she returned. Too quick for her own good, that one, and with a terrible imagination. Why, she could convince a person the devil himself knelt in front of the parlor fire, warming his hands.

Читать дальше