When they’d finished their coffee, Pemberton pushed back his chair and stood but Serena remained seated.

“I have a bit more work to do tonight.”

“I or we?”

“I,” Serena said.

“And it can’t wait till morning?”

“No, better to go ahead and get it done.”

“You’re not well yet,” Pemberton said. “Not completely.”

Serena rose and came around the table and stood before him. She reached her hand behind Pemberton’s head, clutching his hair as she pressed his mouth to hers. She held the kiss, settled her free hand on his lower back and pressed him closer. A full minute passed before she stepped away.

“Still believe I’m not completely well, Pemberton?”

“I’m convinced,” he said. “But still …”

“Go on to the house,” Serena said. “Chaney will be around if I need help.”

Serena took him by the upper arm, led him toward the office.

“Go on, Pemberton,” she said softly. “I’ll join you in just a little while.”

Chaney waited on the porch. As soon as Pemberton went by, Chaney stepped into the office, where Serena had remained. Pemberton walked past Dr. Carlyle’s house, empty since its former inhabitant was found in the Asheville train station’s bathroom with a peppermint between his death-locked teeth. Pemberton mounted the steps to his house and went inside. A counteroffer for the Jackson County tract lay on the kitchen table. He sat down and began to read.

When an hour had gone by Pemberton left the kitchen and stood on the front porch. The office lights were off, dark in the barn and stable as well. He walked over to the porch edge, stared up the ridge and found Chaney’s stringhouse. It was dark. Just as Pemberton was about to go back inside, the moon emerged from behind a cloud. The first full moon of October, what the mountaineers called a hunter’s moon, and at the same moment a stooped figure emerged on Chaney’s porch like something rising out of deep water. The old woman faced not toward the camp but westward.

Serena returned at dawn. She undressed and got in bed, pressed her body against Pemberton’s. He felt the night’s chill in the hand she rested on his side. Serena’s lips lightly touched his, then she settled her head into the feather pillow and slept.

THE FOLLOWING AFTERNOON Sheriff McDowell knocked on the office door and waited for Pemberton to acknowledge him before entering. Pemberton motioned for the sheriff to come in. He did not offer the man a seat, nor did the sheriff ask for one.

“What brings you to the camp that a telephone call couldn’t convey, Sheriff McDowell?” Pemberton said, looking over at the clock for emphasis. “I’ve got too much work to entertain uninvited guests.”

McDowell did not speak until Pemberton’s gaze again focused on him.

“Sarah Harmon and her son were found in the river this morning.”

The sheriff’s eyes absorbed Pemberton’s surprise.

The only sound for a few moments was the Franklin clock ticking on the credenza.

“So they drowned?” Pemberton asked.

“The mother did, or so Saul Parton claims, though he’s not filling out his coroner’s report until someone from Raleigh has a look at her.”

“And the child?”

“His throat was cut. Left to right, so whoever did it was a lefty.”

Pemberton told himself not to look in the direction of the gun rack until McDowell was out of the office. What else not to do, he asked himself, but could think of nothing else. He checked the clock but the minute hand had not moved.

“How long were the bodies in the water?” Pemberton said.

“Parton believes since around midnight.”

“Perhaps the river caused the cut throat,” Pemberton said. “That river is rocky and fast. A body could be tumbled about, cut by a sharp rock.”

The sheriff looked at the floor a few moments as if studying the grain of the wood. He slowly raised his eyes to look directly at Pemberton.

“Do you think we’re utter fools down here?” McDowell said. “Or just so afraid we’ll let you do anything?”

Pemberton resisted the urge to answer.

“I went over to Asheville last week,” McDowell continued. “It’s not my jurisdiction but I talked to the coroner about Carlyle. He said once he got Carlyle’s clothes off he found five possible causes of death. Whoever killed Carlyle had it in for him. I can’t do anything about Abe Harmon or Buchanan or Carlyle, but I vow I’ll do something about the murder of a mother and her child.”

McDowell paused, his voice softer, more reflective.

“There’s something about it,” he said, “seeing a child laid out in a morgue. It takes root in the mind and nothing can get it out.”

McDowell splayed his fingers and ran them through his hair, revealing a few streaks of silver Pemberton had not noticed before. He had no idea how old the man was, though he would have guessed forty-five, maybe fifty.

“When was the last time you saw that child?” McDowell asked, looking at Pemberton now.

“Are you expecting me to say last night, Sheriff?”

McDowell waited.

“June. She brought him to one of Bolick’s services.”

“I seen him about that time as well. He’d grown a lot since then. His face had filled out more, become a lot more like yours.”

McDowell paused, then stared into Pemberton’s eyes as if trying to look through them deep into the brain that lay behind.

“The eye color too,” he said softly, “not blue like his mama’s but molasses brown, not a whit’s difference between that child’s eyes and the eyes I’m looking at right now.”

“I’ve got work to do, Sheriff,” Pemberton said. He peered at an invoice on the desk, raised it slightly as if to better read the numbers.

“I measured a boot print left on the sandbar,” McDowell said. “A distinctive type of boot from the narrow toe, nothing you’d buy around here. From the size and shape I’m betting it’s a woman’s. Now all I’ve got to do is find my Cinderella.”

Pemberton did not raise his eyes from the invoice but knew the sheriff watched for a reaction. After a few more moments McDowell turned and walked out the door. Pemberton watched from his window as the sheriff got in his car and drove back across the ridge toward Waynesville. He locked the office door and went to the gun rack, opened the drawer beneath the mounted rifles.

The hunting knife was in the same place as before, but when he pulled it from the sheath blood stained the blade. The blood was black and appeared to be clotted, but when Pemberton scratched a fleck free and rubbed it between his thumb and forefinger, he felt a residue of moisture.

The phone rang and Pemberton picked it up. Campbell was calling from the sawmill. Almost all the train cars had been loaded. Pemberton’s voice seemed hardly a part of him as he told Campbell he’d be there in a few minutes.

He hung up the phone. The knife lay on the desk, and Pemberton picked it up.

He considered taking the knife to the sawmill and throwing it in the splash pond. He realized that for the first time in memory he felt vulnerable, almost afraid. For a few moments he did nothing. Then Pemberton rubbed the blade clean with a handkerchief, slid the knife in the sheath, and returned it to the gun rack’s drawer.

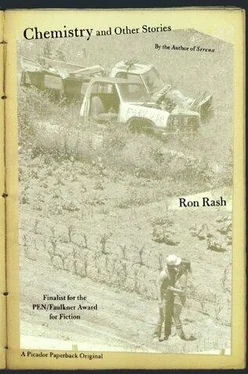

PUBLISHER’S NOTE:

The story “Speckled Trout,” which won a 2005 O. Henry Award, was later altered and extended to become the 2006 novel The World Made Straight. What follows is the story in its original form.

Lanny came upon the marijuana plants while fishing Caney Creek. It was a Saturday, and after helping his father sucker tobacco all morning, he’d had the truck and the rest of the afternoon and evening for himself. He’d changed into his fishing clothes and driven the three miles of dirt road to the French Broad. He drove fast, the rod and reel clattering side to side in the truck bed and clouds of red dust rising in his wake. He had the windows down and if the radio worked he’d have had it blasting. The driver’s license in his billfold was six months old but only in the last month had his daddy let him drive the truck by himself.

Читать дальше