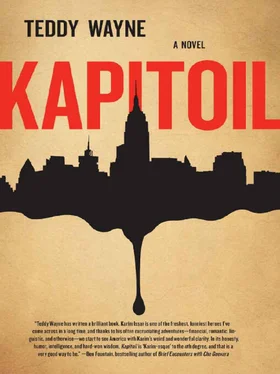

“That’s how I grew my company,” says the tanned and salt-and-peppered 64-year-old, who resides in an Upper East Side penthouse in Manhattan during the week but chooses the subway over cabs and limos (“The subway is fast, cheap, and entertaining; a car is none of those”). “Counting cents.”

Known in business circles as “the Hedge Clipper” for his innovative hedging strategies in the 1970s, when his fledgling company soared while nearly everyone else faltered, Schrub is the closest thing the financial world has to an ambassador. Confidant to senators and celebrities alike, board member of dozens of charitable organizations, and the face of perhaps the most successful financial company of the last quarter century, he ranked first in a recent poll asking graduating MBAs which business figure they sought to emulate.

For now, though, he is looking forward to an afternoon on the high seas aboard his relatively humble — by Greenwich standards—35-foot yacht (named Clarissa , for Schrub’s mother) with Helena and their two sons, Wilson, 21, and Jeromy, 19, on summer break from Princeton. “Sailing is my passion,” opines Schrub, “but I don’t need a fifty-foot boat to prove that to others. I’m not one for conspicuous consumption. There’s nothing inherently wrong with accumulating money, unless that’s all that matters to you.”

The rest of the article is about sailing, and it does not indicate if the soda is Coke, which would interest me more than sailing does, but I like the last quotation, and I consider mailing the translation to Uncle Haami, because of what he said one year ago when I had the opportunity to labor at Schrub’s Doha office. He was eating dinner at our home on a Friday and we were roundtabling my job offer. After being polite for the majority of the meal, Haami finally became upset when I discussed Schrub’s recent record growth. “You will be divesting money from Qatar and into the hands of greedy Americans,” he said as he swallowed the hareis I had cooked.

I was very prepared for this argument. “First, how are they more greedy than Doha Bank?” I asked. “They both aim to create more wealth. Schrub merely possesses more equity. Second, how are we paying for this lamb?”

“It is not money I object to,” he said, which is slightly different from Mr. Schrub’s quotation but has some intersection. “It is the imbalanced distribution. And it is the American economic policy of imperialism.”

I said that companies like Schrub create the largest pool of money, and they can do so only because there does exist an imbalanced distribution of equity, so that the innovators, e.g., Derek Schrub, have enough capital to impact the world around them. I did not say it then, because it might have negated my argument, but the article is correct when it calls Mr. Schrub the Hedge Clipper. It would of course be optimal if everyone infinitely produced wealth, but sometimes only a zero-sum game is possible, and you must hedge to create wealth while others are losing it. And I agree with Mr. Schrub: I am trying to earn impressive wealth not for conspicuous consumption, but to certify that I can pay for half of Zahira’s tuition and so our father can retire from his store before he becomes very old.

“And the correct word is not ‘imperialism,’ but ‘globalization,’” I said. I believe I pronounced the English translation as well. “Globalization creates more trade and jobs for everyone, in both the U.S. and Qatar.”

“I will not argue with you anymore in your father’s home,” Haami said. “What do you think, Issar?”

My father breathed on his gunpowder and mint tea and drank from it and scratched his gray beard before he replied. He looked at my uncle although he was discussing me.

“Karim is a grown man,” he said. “He can make his own decisions.”

He did not say another word then about Schrub, and he has not said anything about it after.

I appreciate that Zahira supported me by saying that I was not designed to labor in a garage, like our uncle, or to sell food and items people want that they cannot purchase elsewhere, like our father, and although that is true and I have more robust plans for myself, I told her after dinner that she should not devalue their jobs, which are integral even if we desire more from life than merely waking up, eating breakfast, laboring for someone else at tasks most people could do, and repeating the same actions daily without personal growth.

The airplane contacts the ground with force, and I close my eyes and contain my breath until the wheels smoothly merge with the concrete and we decelerate.

After I retrieve my luggage, which is minimal because I do not have much clothing and only one additional suit, I see a black man holding a sign that displays “KARIM ISSAR” with large quotation marks and at the bottom is the logo for Schrub Equities of a flying black hawk transporting the letters S and E in its two feet, which infinitely makes me feel proud, but especially now, when I see my name publicly linked to my company. He is approximately 15 years older than I am and has a full mustache and a mostly voided beard, probably because he shaved in the morning.

“I am Karim Issar of Schrub Equities,” I say. I put down my luggage to shake his hand. The name sign on his left pectoral displays BARRON without quotation marks.

Barron does not shake my hand but picks up my luggage. “This all?” he asks.

I nod, because this is the first American here I have talked to besides Brian and the airplane workers and the customs official, and I am nervous about making an error even though his own sentence is incomplete.

“I can carry them,” I say. But Barron is already leaving. I follow him out of the automatic doors of the airport onto American concrete, and my lungs consume the cool air that is like the initial taste of a Coke with ice.

Barron drives a black car, but it is not a limo, and the interior leather is the color of sand and feels like Zahira’s stomach when she was an infant. A photograph inside the sun-protector over his head displays a little girl with braided hair, although it is unlike the fewer and less rigid braids my mother sometimes used to produce for Zahira when our father was at the store.

In the front mirror I see Barron has a small scar above his right eyebrow, which looks like his left eyebrow in the mirror. It is like debugging a program: Sometimes you do not truly observe something until you study it in reverse.

We are on the highway now, although there is not much to see and the sun has already descended. The speedometer is at 55, the optimal rate for consuming gas, so I recall the problem on the airplane. This car is probably not efficient enough with two people to be as efficient as the airplane, but I am curious.

“Excuse me. How much gas does this car guzzle?” I ask.

“Guzzle?” Barron says. “You mean its fuel efficiency? I don’t know.”

“It is not 42 on the highway, is it?”

Barron laughs, but it does not make me feel the way it did when Brian laughed. “Not even close. But if you find one like that, let me know. They make us pay for our own gas.”

The car zooms through the streets of Manhattan like a circuit charge, and the buildings maximize as we get closer. From a distance I identify my new apartment building, Two Worldwide Plaza. On its top is a glass pyramid, and pyramids intrigue me for four main reasons:

1. The Great Pyramid of Cheops is one of man’s superior ventures, yet we do not know with 100 % certainty how it was constructed.

2. The perimeter of the Great Pyramid divided by its perpendicular height approximately equals 2  .

.

Читать дальше

.

.