Bagley’s only real legacy is the group of thirty children he sent to England for a secondary education. When they returned they became the cultural elite of the province, and occupied the most important posts at Guiyang schools and colleges. Not one of them returned to Shimenkan though.

The poverty in these mountains puts me to shame. Most people have never worn shoes. The family I stayed with a few days ago cooked their food on a piece of broken terracotta. They served me a bowl of maize gruel and a cup of salt water, and I gave them my last packet of biscuits. They told me they grew enough grain to eat for two hundred days, and the rest of the year have to make do with husks and potatoes.

That afternoon cadres from nearby villages gather at the committee house to read the central authorities’ 1986 agricultural plan. There are ten Party members, but only five know who Deng Xiaoping is and none have ever heard of Secretary Hu Yaobang. At the close of the meeting, the Party secretary announces that tonight’s mission is to arrest a man who has fathered four children and owes the state thousands of yuan in family-planning fines.

‘We ransacked his house last month, but he still won’t give himself up. He was seen creeping back to his house two nights this week, and leaving before dawn, but his wife will not admit to it and refuses to tell us where he is hiding. Tonight we must surround his house and catch him red-handed. Liu Wang, you place six men in ambush outside his uncle’s home, and don’t forget the torches. The rest of you must guard the village gates.’

In the middle of the night, twenty militiamen arrive at the committee house and wait for their orders. When I see their guns I suspect the peasant will not survive the night.

Surprisingly, though, he surrenders without a fight. The men bring him to the committee house, tie him to a table, open his abdomen and snip his sperm ducts. In the afternoon he squats in the office refusing to leave, but no one takes any notice.

‘Why not go home? Your wife will be getting worried.’ If he stays here all night I will not get any sleep. He rolls his eyes, one hand still clutching his bandaged stomach.

‘I am not going until they give me back my bull.’ Ever since they cut through his skin, he has looked like a deflated football.

‘You haven’t done so badly. You still have four children at home.’ He looks away and ignores me from then on.

The village committee confiscates his door, window panes, roof tiles and farming tools, but these are still not sufficient to cover his fine. At dusk they drag him outside. After a meal of mutton noodles with the village cadres, I open the front door to see if he is still there, but he has vanished into the black night.

Between Daxing village and the Jinsha River, the temperature suddenly rises, and banana and prickly-pear trees appear by the side of the road. I cross the river at dawn and start my ascent of Mount Daliang. At noon it is so hot I climb stark naked, but when I reach the two-thousand-metre peak I shiver in my down jacket.

That evening I reach a village called Mayizu and stop for the night. A Hong Kong-Shenzhen production is shooting a movie here and has transformed the village into a film set.

In the morning, the Yi villagers dress in their national costume and parade through the mucky lanes, laughing and kicking dogs out of the way. No one goes to work on the fields. When the crew start shooting, the Yi follow them from location to location, brandishing wooden chests, hip knives, earrings and bracelets, hoping the director will need to hire them for the next scene. When the director picks someone for a role, they moan at the injustice. They cannot understand why the dirtiest layabouts and ugliest women are always given the best parts. After the director shouts, ‘Action!’ the villagers start laughing and crying as if they were watching a film at the cinema. The puny director’s constant pleas for quiet are translated into Yi by the security guard sent down from the county town.

The film is based on the true story of an American pilot who parachuted here in the 1940s after his plane was shot down by the communists. The Yi found him and made him their slave, and it was nine years before they let him leave their mountain enclave and return to America. They would never have imagined that the ‘foreign monkey’ they released would one day bring them such fortune. The Hong Kong director is at his wits’ end. ‘This is a nightmare,’ he says. ‘The Yi charge us for everything, and their prices go up every day.’

Money has changed these people’s lives and their way of thinking. What would I do if I came into some money now? Would I still be wandering through these mountains? My poverty allows me to move as freely as a leaf in the wind, but sometimes I wish a stone would fall on me and pin me to the ground.

The American pilot was able to stay here all those years because he had a goal in life: he wanted to go home. I have no such goal, so I must keep walking.

I check my compass, head south and a week later arrive at Yunnan’s capital, Kunming.

On 2 June, two hours after leaving Baoshan, the long-distance bus stops at a small hamlet, halfway up a steep mountain valley. The driver jumps off and says he needs to find some water for the engine. The passengers start lighting cigarettes. The baby next to me wakes and screams. His mother lifts her vest and stuffs her left nipple into his mouth. The bus is hot and stuffy.

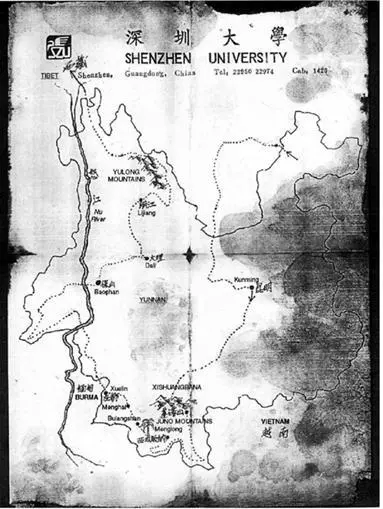

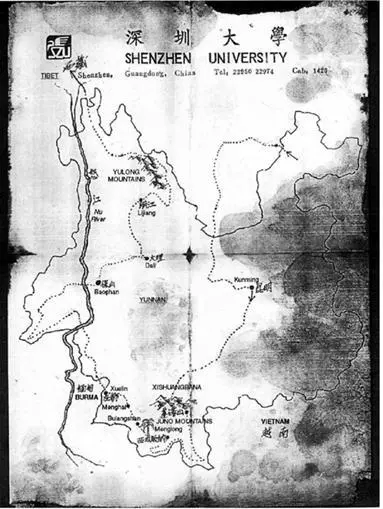

This is my second month in Yunnan. Six weeks ago, I gave a lecture on modern poetry at Kunming University which attracted a small audience. The next day the students told me their university’s propaganda department had issued a warrant for my arrest. The alleged crime was ‘disseminating liberal propaganda to impressionable youths’. I ran away to the border region of Xishuangbana, but on my second day in the capital, Jinhong, the poet who was hosting me said the local writers’ association had received notice that an officer had been sent to Beijing to investigate my case, and that pending the results, they should have nothing to do with me. He gave me a nervous glance and said, ‘Please, if they catch you, tell them we’ve never met.’ I left town and headed into the mountains, and have been racing through the borderlands since then like a hunted animal.

The baby has fallen asleep again. I open the window, take out my notebook and read through the last few entries.

28 April. Still wandering through the Jinuo mountains in the Xishuangbana region of southern Yunnan. The landscape is green and tropical. I have seen oil palms, papaya trees, pineapple trees, tropical orchids, climbing wisteria, fire flowers blazing on rotten wood, leafless bachelor trees and chameleon trees with leaves that change from yellow to green to red. The slopes cleared twenty years ago by city youths to make way for rubber-tree plantations are now dry and barren. By the banks of the Pani River, I saw the graves of fourteen youths who died in the fires. Two of the tombstones bore the inscription: POSTHUMOUSLY AWARDED MEMBERSHIP OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY.

The Jinuo village I am staying in has a long bamboo house that is shared by 29 families who belong to the same clan. The families live in separate rooms, but cook their meals on a communal fire in the long central corridor. The house is cluttered with farm equipment, baskets and stools. There is little attempt at decoration.

Jinuo custom allows members of the same clan to fall in love, but not to marry. When the time comes for a clan couple to separate, they exchange gifts with each other as pledges of undying love. The girl gives a leather belt and the boy gives a felt bag. These gifts are then taken to their new marital homes and displayed on the wall. When the clan lovers die, they carry their gifts to the mythical Nine Crossroads, meet up and travel together to the underworld where they can marry each other at last. For the Jinuo, husbands and wives in this world are mere companions of the road, true love must wait for the afterlife. I have seen these belts and bags hanging on the walls of several village huts. When a girl gets married, her clan lover splashes her with water from a dirty washing-up bowl as a show of jealousy. It is considered a great humiliation for a bride not to be drenched at her wedding. Jinuo women wear white, peaked hats and long black skirts.

Читать дальше