I hear a muffled chanting and trace the noise through a dark corridor to a chapel behind where thirty or forty child monks are sitting cross-legged on the floor. I quietly kneel in the doorway. The old lama leading the prayers is the first to see me. Then two child monks peer round and soon the whole room is staring in my direction. I stay where I am. After a while the chanting peters out. The little monks laugh and prod each other, then rush over and engulf me.

‘What’s this temple called?’ I ask.

‘Nyima Temple.’

‘How old are you?’

‘Ten.’

‘And you?’

‘Eleven.’

‘And you?’

‘Ten.’

‘Twelve.’

The old lama storms over and barks in broken Chinese. I show him my identity card and explain I am a journalist from Beijing. His expression changes. He thinks for a second and asks, ‘Where’s your car?’ When I tell him it is parked at the bottom of the hill, he relaxes at last and joins the crowd of little monks who are examining my camera and denim jeans. I ask to take their picture and they arrange themselves at once into three neat rows.

One of the novice monks speaks Chinese. He shows me the dormitories, dining room, printing room, even the wild-dog den on the other side of the hill. He says his father is Tibetan and his mother is Han Chinese. He spent six years in a Chinese school, before his father had a change of heart and sent him to the monastery. He does not like chanting sutras and wants to be a truck driver when he grows up. He has two little sisters and his father is a local government cadre. He tells me his Tibetan name is Sonam, his Chinese name is Xu Guanyuan, and he is not sure which one he likes best.

In the afternoon, I leave the monastery and return to the committee guesthouse in Maqu. The straw pillows are rough and noisy and stink of insect repellent. In my dreams that night I see a Tibetan butter pouch made of soft suede. When I squeeze it between my hands it gasps, and moans, ‘Stop it, you’re hurting me. .’

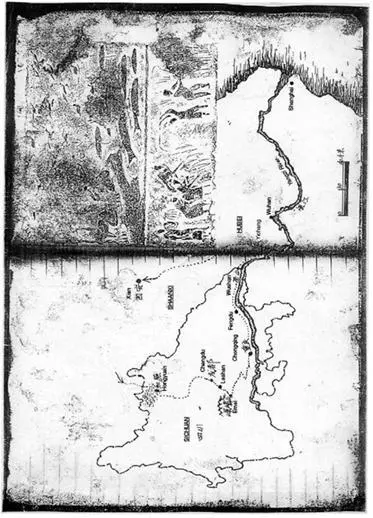

The next day, I fill my water bottle and leave Maqu at dawn. Another dirt road stretches ahead, not a truck in sight. I scratch my flea bites with a twig and walk for hours until my head throbs. At last I reach Langmusi village — a few stone shacks clustered around a fork in the road. All the doors are padlocked. It looks like a roadworkers’ camp. The tall mountain behind is dotted with sheep. A shepherd boy stares down at me from a rocky outcrop. The summit is a sheer stone cliff. I look at it for a while, then take the road that curls to the right.

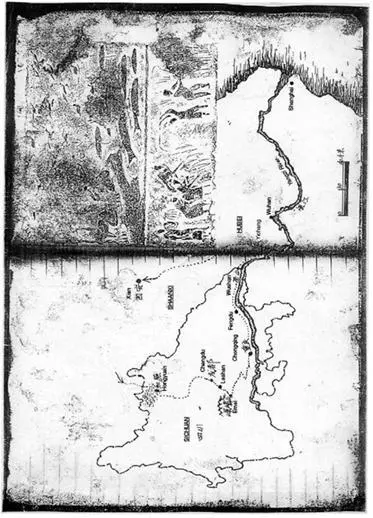

On the other side of the mountain, I see the fertile basin of Sichuan sweep to the south. I stop and think back on my route through Gansu and Qinghai. I think about the puppy I carried in my arms, the girl in the red blouse, the monk called Sonam who dreams of being a truck driver, and I wonder what they are doing now.

I spend the night in a hostel attached to a petrol station outside the village of Redongba. The electricity is turned off at dusk. I fetch a basin of hot water and wash my feet and socks by candlelight. The bedcovers are filthy and full of fleas, so I douse myself with tiger lotion, lie on the bed fully clothed, and escape at the first light of dawn.

The road soon leaves the mountains and cuts into the Songpan meadows. In 1935 Mao Zedong led the Red Army through here in what proved the most arduous stretch of the Long March. The grass is green and lush, but beneath it lies treacherous swamp. I remember the pictures in my history textbook of soldiers and horses sinking into the mud. It is still not known how many died — hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands. The ones who survived the marsh are the founding fathers of today’s communist tyranny. No one has thought to retrieve the bodies of the dead soldiers and give them a proper burial. All that disturbs the meadows now are the red poppies wavering in the wind.

As I scan the swathes of grass and inhale their perfume, my mind fills with images of death and misery. Under my breath I sing a song from the revolution: ‘The Red Army climbs a thousand mountains and crosses ten thousand rivers, yearning for a moment of rest. .’

I stay off the grass and tramp for hours on end, watching noon change slowly into dusk. After three days I lose interest in the scenery and keep my eyes on the road. On the fourth day, I reach Hongyuan as a cold rain begins to fall.

The guesthouse I book into is an old-fashioned two-storey building with wooden floorboards and a veranda at the back. The pillars flanking the front door are still marked with the peeling red slogans ‘Long Live Chairman Mao’ and ‘Long Live the Communist Party’. I take a stool onto the veranda, light a cigarette and watch the raindrops burst bubbles on the puddles in the backyard. I remember as a child how excited I would get at the first glimpse of rain. I would run outside and build mud banks across the gutter so I could wade in the puddles behind. I never got very far though — someone would always cycle through my dam before I had finished building it. Now, as I stare at the rain and look at my muddy shoes and crinkled white feet soaking on the wet floorboards, I feel tired and a long way from home.

In the evening I have a beer and close my eyes. I have a whole room to myself and it costs just two mao a night. This must be the cheapest hotel in China. I decide to stay a few days and take things easy.

The first day I have a shower and wash my clothes.

The second day I stroll into the meadows and take photographs of Tibetan prayer flags. The Buddhist sutras printed on the cloth murmur in the breeze.

The third day, I take my blanket onto the veranda and shake out the dust. Then I walk through the village and buy a Tibetan knife.

The fourth day I walk to the next hill. Rain clouds fill half the sky while the other half bathes in sunlight.

The fifth day I write some poetry, mend my socks and drink a bowl of fresh oxblood bought from the local abattoir.

After two weeks I finally leave Hongyuan and catch the morning bus to Chengdu.

Yang Ming and I walk out of the concrete building that has baked all day in the Chengdu sun, and squeeze ourselves onto a bus that is even hotter than the editorial office we have just left. When the doors close I feel oppressed, not by the number of passengers, but by the stale stench of the noisy steam that rises from the city.

‘It’s easier to get on buses here than it is in Beijing,’ I say.

‘It is if you look as bad as you do.’ Yang Ming has a voluptuous figure, but she speaks and moves like a man. She was the eight hundred metres racing champion one year at her university. We clutch the hot rail. My fingers look dark and chapped next to her delicate, white hands. ‘My boss rejected "Escarpment", so I sent it to a literary journal published by Guizhou Press,’ she says. ‘It’s got past the lower committee. The editor, Old Xu, is a friend of mine. He likes your style. I told him you are travelling the country and he said you should look him up if you visit Guiyang.’

The last time I saw Yang Ming was in Hu Sha’s room. She had come to Beijing to recite her poetry at a literary conference.

She is wearing brown jeans today. Her large round eyes stare vacantly at my beard. I cannot connect her with the Yang Ming I saw last winter in the red knitted hat, so I resort to discussing mutual friends.

The road is packed, but the bus sways like a fish above the sea of faces and the silver light thrown from the metal handlebars. When we pass the main square the cyclists thin. Ahead, a huge statue of Chairman Mao, one arm raised in salute, towers above a smoking chimney stack behind and makes the pedestrians seem much smaller.

Читать дальше