The elevator halts with a jerk.

I’m not scared. Elevators get stuck every day, somewhere. I look at the man.

He starts jamming the heel of his palm into a lever beside the buttons. The V of veins deepens. “Don’t worry about it,” he says. “Happens all the time.”

I try to say, “I’m not worried,” but the words get stuck in my throat like phlegm and I can’t spit it out. I’m chewing on it. He bangs on the lever again and a bright shiny brick of gold falls out of his back pocket. But it’s not a brick of gold, it’s a National Geographic that’s been rolled and bent and loved. There’s a huge macro photograph of a bee on the cover.

“Bee,” I say and point. There was a sentence that went around that word in my head.

He bends down to pick it up, forgetting the lever. “They’re disappearing. Did you know that?” He shakes the magazine and I shake my head. “A friend got me interested. She keeps a hive in the city. Totally illegal. They’re just vanishing. Poof.” I shake my head again. He hits the magazine against his palm a couple times. “Here, take it.” He shoves it in my hand. “I’m finished with it.”

There’s a groaning noise, the elevator is talking and jerking and I let my mouth hang. But he just smiles wider and we start moving down, slow and smooth. It takes forever, actually. And when it seems we’re almost at the bottom, I say, “Hey, thanks.”

And the guy keeps smiling and says, “No problem.”

But we’re not down yet like I thought. I look at the doors. “So, is this your building?”

He looks at me like he’s never been asked that before and shrugs. “Something like that. Custodian.” I can’t help staring at his thick head of hair while he talks. It’s wavy and gray, short but not too short. Exactly the kind of gray I want to have. It seems to light up when I look at it and is so full I almost touch it. Then, as if he can read my thoughts, he runs his own hand through his hair. “Yeah. It’s all right. Just started a few weeks ago. I can get into any gallery. I can look at art in the middle of the night if I want.”

“Do you?”

“No.”

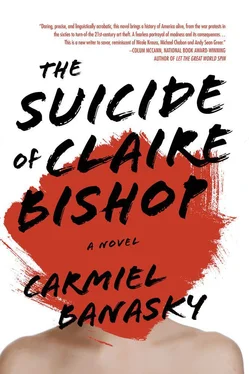

“I went to see The Suicide . The painting called The Suicide .”

He stares at me for a moment, nervous-looking, his face shining with sweat, giving off light like his hair. He takes a breath like someone trying to not get angry. Then he reaches out his hand. “My name’s Jill.”

I give him my hand but I can’t give him my name. Not until I know it’s safe.

“Yeah, yeah. My folks wanted a girl, I guess.” Jill laughs at that, then says, “I guess you like her art?”

“Yeah.” My best nonchalant voice, juggling the magazine in my hands. “Don’t you?”

Jill shakes his head. “Can’t say. Can’t say I do.”

“I know her,” I say. And then we hit bottom and I want to pull my ears out for telling him that. Jill doesn’t even respond. Actually, and this can’t be right, he looks ready to cry.

I mumble thanks and hurry out into the street and the stupid day without her painting.

In the hospital last year, my psychiatrist asked what words were the most hurtful. He called it a wellness strategy — to pick the words that I found the most harmful concerning my disease, and to take them out of my vocabulary. He was a young guy fresh out of med school and had the weekend shift. Bursting with unconventional ideas. They’d just switched my diagnosis from schizophreniform to schizophrenia. And I felt kind of at a loss. They could just take away or replace.

We settled on the two words. “Let’s rip them out of the dictionary,” he said excitedly, “to make it official.” He brought over a big old Webster’s, its hard cloth cover frayed at the corners. “It’s okay. I got it used.” Scissors weren’t allowed, but the pages were thin enough I could use my fingers (though there may have been some extra, inadvertent victim words). He sat back with his hands clasped behind his head and watched me flip first to the S’s, then to the C’s. I extracted those two normal-seeming words. The ones that had disappeared until Nicolette texted them the other day. The ones she shouldn’t have. All it took was a thumbnail.

The Chelsea lofts are gray clouds against a gray twilight sky. Far away, black birds drift like a man’s stubble. If only I had the painting under my arm.

The 1950s. How can it be hers? Had I not held her just a year ago? But it is her painting. It doesn’t matter if it was painted in 1952 or 26 B.C. It is possible. No one will believe me, not the gallery sitter or the Hasidic owners or her fans on her guerilla art website. But it is hers.

A bee buzzes near my ear and I flick the National Geographic to shoo it, but when I look around I don’t see anything.

I have a talent for memorizing the weather. I get real cold and can feel the sleet in my hair when I think about the day my mom forgot to pick me up after a chess tournament in Tacoma. Or I sweat when I remember Jules’s wedding day three summers ago in a synagogue without air conditioning. I memorize weather like I’m cramming for a test, but maybe more like recalling the taste of grapefruit when you haven’t had one in months, tongue puckering. As for today, I’ll never shake the humidity.

It’s not dark yet, but the sun is down. Dusk is the truest time. All that ambiguity freshly unmasked from the seeming certainty of daylight. The certainty the sun imposes on lines. At dusk, lines meld together, you can’t tell the beginnings or ends of things, buildings melt into streets melt into telephone poles melt into my body. And the reality of the physical world, the day, it says, So long, Chelsea town, so long.

I walk down Eighth Avenue until the sky is the color of the street. Past the nearest subway stop, down on to the next. I want to walk. I want to feel the bones in my feet, because she’s here, she’s out here. I pause as a few notes drift out of a lit-up shopfront, trumpeting the sidewalk, looping in and out as if the night were at moments muting the music, at moments inviting it to move in and rise, like a fellow player at a jazz club, taking a solo, giving one. The repeated phrase takes a turn and it’s coming for me, violent for a moment, but the crescendo relaxes, sinks a bit in on itself. And there, in the display case of that shop window, is a large vase, and the design on that vase is exactly the visual representation of the song being played. It is blue and white with loops along the top, dots in the center, loops again below, a Dutch pattern but it’s all jazz. Art and intention all around — that craftsman knew I’d be looking at that vase at the end of dusk with jazz in my ears. How all things, all senses come together — when that happens I fill up and am so grateful for the pulse and life of the city.

I must lower my dosage. One pill per day instead of two and we’ll see how it goes. How else will I be able to find the truth? It all makes sense. But the sense of it is so heavy. I can barely hold it in my head. It makes so much sense I’m scared of it. But I will find the truth. I will find Nicolette. And you’ll help me, Loyal Voices.

I spread the magazine over my head. A light drizzle starts, and tonight will be wretched. All the summered people in the street, we all watch the city through a thin screen, gray and lit from afar like a movie, but the screen is also touching all of us, connecting us. Threading us through with water from the same cloud. This is what I’ve missed. Monday almost over. Tonight it will rain. Tomorrow the street will be different.

PART III: THE PROTEST MARCH 26, 1966

The marchers came in small groups. Countable, until they were no longer countable. Police appeared on cue. And suddenly the street was blocked to traffic and Claire couldn’t cross Eightieth. In a matter of minutes she could hardly see the ground. Thousands swarming from the north, and Claire found herself — of all the places and days — in the heart of a protest.

Читать дальше