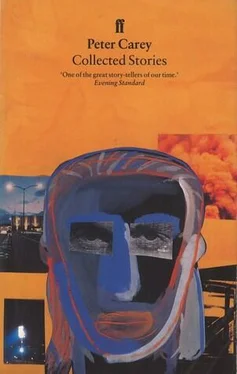

Peter Carey - Collected Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Carey - Collected Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Faber and Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Collected Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber and Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Collected Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Collected Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Collected Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Collected Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Doubtless you think me a poor fellow, forever watching, never travelling, my red hands gripped around the wire mesh, doomed to be left behind, to watch from cuttings, to peer from bridges, to stand amongst thistles in driving rain whilst the train passes me by and leaves me to walk two miles through muddy paddocks and wait for a bus to take me back to my room. If you think me pitiful, you are not alone. My co-workers have belittled me, taken every opportunity to play some cruel trick on me and in general have acted as if they are in some way superior, and all the while they have complained about their own lot, the monotony of their lives, the injustice of the state, the cruelty of their superiors. Little did they know how I pitied them, how I laughed at their presumption that they might one day control their own destiny.

But I, I have not complained. I have worked day in, day out, forever filing away the mountains of paper which record the business of the state: births, deaths, marriages, all tucked away in the right place so they can easily be found when needed. I have filed acts of parliament, executions, stays of execution, punishments of greater and lesser degree, exhumations, cremations, promotions and so on. When my clothes have become worn I have spent my precious savings in order that I might do honour to my lowly position and not disgrace my superiors.

My colleagues’ frayed cuffs and stained suits have appalled me. Their scuffed shoes, their dirty hair, their missing buttons have affronted me day in and day out for nearly thirty years.

They have thought me vain, foolish, lonely, pathetic but they, like you, do not know everything, and when they hear of my reward, my gift, my privilege, we will see who is laughing at who.

For I, Louis Morrow Baxter Moon, am to travel on the train on official business.

Ha.

Today I have been to the bank and withdrawn my savings, every penny. I have purchased a new suit, a pair of shoes, one pair of dark socks, and I still have some not insubstantial amount left to cover such items as tips and wine. The state, of course, will pay normal expenses but I do not intend to travel as a lackey.

In addition I intend to drink gin and tonic.

2.

The ticket is palest pink, denoting a journey of two thousand miles. A black diagonal line across the corner entitles me to a private salon of the second rank which, humble as it may sound to the uninitiated, is more sumptuous than anything my co-workers will experience if they live to be three hundred years old.

The ticket is held between two gloved fingers. I hand it to the man on the gate. He looks at me quizzically. Does he remember me? Has he seen me here on Sunday mornings and is he now indignant that I shall at last pass through his gate? I stare him down. He waves me through and I enter the platform with my heavy suitcase.

I had expected a porter to rush to my service, but this is not the case. All around porters carry cases belonging to other passengers. Perhaps my dress is not of the style normally worn by travellers. I carry my case without complaint. In any case it will save me the difficulty of tipping. I would rather save the money for other things.

I experience a strange sense of unreality, perhaps explained by my sleepless night, the curious nature of the mission that has been given me, the experience of walking, after so many years, on the platform itself. How often have I dreamed of just this moment: seeing myself reflected in the large windows of the carriages, a ticket in my hand, ready to board the train.

Through the windows of the dining car I see maids laying tables with fine silver. Three wine glasses are with each setting and do not think that when the time comes I will not use at least two of them.

I present myself at car 23 and hand my ticket to the steward.

“Who is this for?” he asks. He is red-haired and freckled-faced. His elegant uniform does not disguise his common upbringing. I do not like his tone.

“It is for me. Mr Moon. A booking made on the account of the State, on whose business I am travelling.”

“Ah yes, I see.” He seems almost disappointed to have found my name in his register. His manner is not what I would have expected.

He allocates me the salon next to his office.

“Here we are.”

“Is this over the wheels?” I ask this as planned. It is well known that a salon directly over the wheels is less comfortable than one between the wheels even though the rails are now laid in quarter-mile sections, thus eliminating the clickety-clack commonly associated with trains.

“It don’t float on air,” he says and somehow thinks that he has made a great joke. He leaves, laughing loudly, and in my confusion I forget to open the envelope I had marked “Tips”.

Any feeling (and I will admit to the presence of certain feelings) that he has somehow given me an inferior salon soon disappears as I investigate.

3.

The salon, in fact, was roughly the same size as my room. But there the similarity ended. The floor, to begin at the bottom, was covered with a plush burgundy carpet so soft and luxurious that I removed my shoes and socks immediately. There were two couches, not velvet, as I had expected, but upholstered with soft old leather and studded along the fronts with brass brads, each one gleaming and newly polished. The bed stood along one wall, a majestic double bed with high iron ends in which I discovered porcelain plaques depicting rural scenes. The bed, of course, could be curtained off from the rest of the salon and one reached the toilet and shower through a small door disguised as panelling. The wallpaper was a rich wine red, embossed with fleurs-de-lys.

I placed my case high on the rack above the bed, put my shoes and socks back on, and retired to the leather couch. From this privileged position I could watch the other passengers pass by my window without appearing in the least inquisitive. Then, remembering the matter of the tip, I removed two notes from the envelope in my breast pocket, folded them, and slipped them lightly into my side pocket. Then I rang the bell.

He took long enough to come.

“Yes?” He just stood at the door, staring in. I would have no more of this.

“Please enter.”

He entered reluctantly, tapping a pencil against his leg with obvious impatience.

First, the tip. I’m afraid the manoeuvre was not gracefully executed. Perhaps he thought I wished to hold his hand, how can I tell? But he stepped away. I clutched after him, missed, and finally stood up. Abandoning all pretence at subtlety I displayed the notes. His manner changed.

“Now,” I said, retiring to the couch, “there are services I shall require.”

“Yes, sir.”

It would be an exaggeration to say that there was respect in his voice, but at least he used the correct form of address.

“For a start I will be drinking gin and tonic.”

“Gin and tonic, sir.”

“And I wish there to be plenty of ice. On occasions I believe the ice can run out very early, is this so?”

“You don’t need to worry, sir.”

“Then I shall require a reservation in the dining car and after dinner I wish a …” and here, I blush to remember, I hesitated. I had been so intent on not hesitating that I did.

“You wish, after dinner?”

“A courtesan.”

“A what, sir?”

“A courtesan.”

“You mean a woman, sir?” I swear he smirked. He had me there. Perhaps the term courtesan was not in common use amongst the lower classes from which he came.

“A woman, a courtesan,” I insisted.

“And ice.”

“And ice.”

“Will that be all, sir?”

“That will be all.”

He left me. Was he smiling? I couldn’t be sure.

My pleasure in the train’s departure was marred by my embarrassment over this incident, but as the train passed through the slums I called for my first gin and tonic. The ice was clear and cold and the drink quickly restored my good spirits.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Collected Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Collected Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Collected Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.