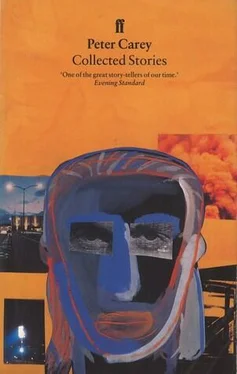

Peter Carey - Collected Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Carey - Collected Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Faber and Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Collected Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber and Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Collected Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Collected Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Collected Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Collected Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I’m beginning to wonder if I’m not emotionally dependent on the drama he provides me. What other reason is there for keeping him here? Perhaps it’s as simple as pity. I know how bad he is. Anyone who knew him well wouldn’t let him in the door. I have fantasies about Vincent sleeping with the winos in the park. I refuse to have that on my head.

“How many people answered your ad?” I asked.

“Only you.”

Thus he makes even his successes sound pitiful.

Tonight I have made a resolution, to exploit Vincent to the same extent that he has exploited me. He has a story or two to tell. He is not a poet. He was never in Long Bay. But he has a story or two. One of those interests me. I intend to wring this story from Vincent as I wring this Wettex, marked with his poor weak blood, amongst the dirty dishes in the kitchen sink.

Before I go any further though, in my own defence, I intend to make a list of Vincent’s crimes against me, for my revenge will not be inconsiderable and I have the resources to inflict serious injuries upon him.

Vincent’s first crime was to lie to me about having been in Long Bay, to ask for sympathy on false grounds, to say he was a poet when he wasn’t, to say he was a reformed alcoholic when he was a soak.

Vincent’s second crime was to inflict his love on me when I had no wish for it. He used his dole money to send me flowers and stole my own money to buy himself drink. He stole my books and (I suppose) sold them. He gave my records to a man in the pub, so he says, and if that’s what he says then the real thing is worse.

Vincent’s third crime was to tell Paul that I loved him (Vincent) and that I was trying to mother him, and because I was mothering him he couldn’t write any more.

Vincent’s fourth crime was to perform small acts that would make me indebted to him in some way. Each time I was touched and charmed by these acts. Each time he demanded some extraordinary payment for his troubles. The wall he is propped against now is an example. He built this wall because he thought I couldn’t. I was pleased. It seemed a selfless act and perhaps I saw it as some sort of repayment for my care of him. But building the wall somehow, in Vincent’s mind, was related to him sleeping with me. When I said “no” he began to tear down the wall and call me a cockteaser. The connection between the wall and my bed may seem extreme but it was perfectly logical to Vincent, who has always known that there is a price for everything.

Vincent’s fifth crime was his remorse for all his other crimes. His remorse was more cloying, more clinging, more suffocating, more pitiful than any of his other actions and it was, he knew, the final imprisoning act. He knows that no matter how hardened I might become to everything else, the display of remorse always works. He knows that I suspect it is false remorse, but he also knows that I am not really sure and that I’ll always give him the benefit of the doubt.

Vincent is crying again. I’d chuck him out but he’s got nowhere else to go and I’ve got nothing else to trouble me.

I can’t guarantee the minor details of what follows. I’ve put it together from what he’s told others. Often he’s contradicted himself. Often he’s got the dates wrong. Sometimes he tells me that it was he who suggested Upward Island, sometimes he tells me that the chairman mumbled something about it and no one else heard it.

So what happens here, in this reconstruction, is based on what I know of the terrible Vincent, not what I know of the first board meeting he ever went to, a brand-new director who was, even then, involved with the anti-war movement.

The first boarding meeting Vincent ever went to took place when the Upward Island Republic was still plain Upward Island, a little dot on the map to the north of Australia. I guess Vincent was much the same as he is now, not as pitiful, not as far gone, less of a professional Irishman, but still as burdened with the guilt that he carries around so proudly to this day. It occurs to me that he was, even then, looking for things to be guilty about.

Allow for my cynicism about him. Vincent was never, no matter what I say, a fool. I have heard him spoken of as a first-rate economist. He had worked in senior positions for two banks and as a policy adviser to the Labor Party. In addition, if he’s to be believed, he was a full board member of Farrow (Australasia) at thirty-five. It is difficult to imagine an American company giving a position to someone like Vincent, no matter how clever. But Farrow were English and it is remotely possible that they didn’t know about his association with the anti-war movement, his tendency to drink too much, and his unstable home life.

In those days he had no beard. He wore tailored suits from Eugenio Medecini and ate each day at a special table at the Florentino. He may have seemed a little too smooth, a trifle insincere, but that is probably to underestimate his not inconsiderable talent for charm.

Which brings us back at last to the time of the first board meeting.

Vincent was nervous. He had been flattered and thrilled to be appointed to the board. He was also in the habit of saying that he had compromised his principles by accepting it. In the month that elapsed between his appointment and the first meeting his alternate waves of elation and guilt gave way to more general anxiety.

He was worried, as usual, that he wasn’t good enough, that he would make a fool of himself by saying the wrong thing, that he wouldn’t say anything, that he would be expected to perform little rituals the nature of which he would be unfamiliar with.

The night before he went out on a terrible drunk with his ex-wife and her new lover, during which he became first grandiose and then pathetic. They took him home and put him to bed. The next morning he woke with the painful clarity he experienced in those days from a hangover, a clarity he claimed helped him write better.

He shaved without cutting himself and dressed in the fawn gaberdine suit which he has often described to me in loving detail. I know little about the finer details of the construction of men’s suits, so I can’t replay the suit to you stitch for stitch the way Vincent, slumped on the floor in his stained old yellow T-shirt and filthy jeans, has done for me. I sometimes think that the loss of that suit has been one of the great tragedies of Vincent’s life, greater than the loss of his fictitious manuscripts which he claims he left on a Pioneer bus between Coifs Harbour and Lismore.

But on the day of his first board meeting the suit was still his and he dressed meticulously, tying a big knot in the Pierre Cardin tie that Jenny and Frank had given him to celebrate his appointment. His head was calm and clear and he ignored the Enthal asthma inhaler which lay on his dresser and caught a cab to the office.

Whenever Vincent talks about the meeting his attitude to the events is ambivalent and he alternates between pride and self-hatred as he relates it. He has pride in his mental techniques and hatred for the results of those techniques.

“As a businessman,” he is fond of saying, “I was a poet, but as a poet, I was a fucking whore.” He explains the creative process to me in insulting detail, with the puzzled pride of someone explaining colour to the blind. He is eager that business be seen as a creative act. He quotes Koestler (who I know he has never read) on the creative process and talks about the joining of unlikely parts together to create a previously unknown whole.

There were a number of minor matters on the early part of the agenda, the last of which was a letter from the manager of the works at Upward Island. Upward was a vestige of an earlier empire when the company had been heavily involved in sugar, pearling, and other colonial enterprises. Now it was more an embarrassment than a source of profit and no one knew what to do with it. No one in the company was directly responsible for affairs there which is why such a trivial matter was now being referred to the full board for a decision.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Collected Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Collected Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Collected Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.