The man is scented with patchouli, his hair, a buoyant ash-grey; it’s not Gull, it’s not my father. Who is this? He’s got earphones, he’s connected to a red plastic box. Broad, full-chested. Not one of the workers.

The Brides. The dance of the Pleiades. Not Orion: O’Ryan, the Huntsman. He’s transcribing arcs of pure motion. He’s smoking. The speed of nerve gives him an amphetamine stutter.

It’s Joblard.

And again he has worked a transformation. He has got out of himself, folded back all the inessentials, all the human tentacles, packed them — so that his form is dense. The shell is hard, but more brittle.

Drink runs through the skin of my head, never gets inside me. He calls for more. The glass is taller; I roll it across my brow.

Joblard is making some kind of confession. I can’t take it in. Trust is fractured and will have to be remade. He has mutilated the previous, the creature that he has impersonated for so long: by choice become a new man and, yes, there is a new woman.

The orphan is, again, his own father. And because of this is an orphan once more. He is cutting himself loose. Mad with pain. And mad with new pleasures. Unshaven, drinking it, the long weekend.

Unwilling; I am implicated. Soon and sudden. Behind the thin walls, an inhuman voice: ‘Don’t break the ring!’

‘It is remarkable that the skin of the penis and scrotum was perfectly normal in every respect.’

Merrick allows the room to perform its cellular function. The long evening slides over his window; brick dust, the shadows of birds. A nurse, crisp scratch of her skirts, pokes at the coals in his grate. The moment holds breath, like a studio oil, darkens into its frame.

His sitting room. A doll’s house. Silver tongs. Ornaments, pictures. Volumes in fine bindings; quite a respectable collection. Hair stroked across his wrist, sensitised. No mirror: the doorspace filled, suddenly, by his protector.

‘A little excursion.’

Curtains shutter low theatre lights that lift the eyebrows. Demonic masks of glittering, scale-like paint. Hell poses. Slow dancer struggling to lift their dead limbs.

The coach summoned.

Joblard is pursuing the invisible.

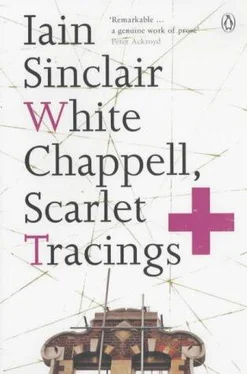

‘I want to make tracings of unseen acts. To flood locked rooms with chemicals that trap the slightest movements of light. To cover all the marks of my own complicity. I want erasures. Weak illumination of ink. Shaded bulbs hung over parchment. The word “whisper” in some unknown language. I want the acts to repeat. I want to measure the force of decay in bread, the glow in the bones of mackerel. To erase time and to bend its direction of flow.’

I don’t know if he is saying this to me, or hearing it on his headset: or if I am making him speak. My fever rubs out the connections. The defences are all down and the shift is on.

I know there is nothing to be written: all writing is rewriting. That old dream: completed books that will never be transcribed, made redundant by their own conception.

The room has filled, but the dance is unbroken. The dancer slips off a black gauze shirt; her body is young, younger than the last time. I can only watch the reflection in the mirror behind her. A shudder of rhythm through her back, slowed convulsion, as she sways her shoulders. She is detached from what she does and detached from her audience. The act is ritualised. Curse and blessing of Enkidu. The pearl. The shed of feathers. She gleams; her hands lifting and covering her breasts.

*

Now Treves was beginning to take a positive relish in introducing Joseph to new experiences: subtle pleasures could be derived from watching.

Joseph was bathed; fussed over by nurses, tub dragged before the fire, thick warm towels. Treves hovering, always, hand on hip, fingering the links of his watchchain. Escorted into the evening, not knowing if he would ever return: the purpose of his journey a mystery. To make it a routine: that each day should be a rehearsal for the next.

Out on his stick, the coachman’s arm about his shoulders; across Bedstead Square, the herb garden, to the street. Lifted into a sealed cab. A flick at the horses. Treves, arms folded, smiling; blocks the window.

Those first autumn evenings: mildness, death. Hay on the pavements. Bales brought on carts to market. Horsedung. Groups in the doorways of public houses. Political meetings.

The route was varied but the duration, seemingly, fixed. No conversation. Tense, rapt. The interval between these excursions was not to be anticipated.

He walked the labyrinth for fifteen years, never encountering the minotaur. The minotaur is outside. We only plunge deeper into our own confusions: turn away and the maze unravels. It is a ghost trap. Walk its length out into the countryside. The path drops through barley fields to Landermere, the estuary. And is repeated in a meander of ditches.

Open the gates of the heart. We force ourselves against the valve. The seals are there to be broken. Upon the door of a decayed greengrocer’s shop, Virginia Road, is painted the map of the labyrinth.

The artist has ‘gone away’, associate of villainy: his grievous body, harmed. His oils dumped among potato sacks. Violent panels. Brawling heads scratched among pint pots. Palette dipped in industrial slurry. He has located the fear and nailed it to his door.

His wife has gone. Tear it down. He is betrayed. The names of birds mark the entrance-gates: from Birdcage to Spread Eagle. Beasts guard the exits: avatars of the Black Bull. Blast them with red light, shatter them in a furnace of sound.

She is twisting, on her back: the floor. As if sacrificed. They close in, tight, to cover her with coins. Naked to the pelt. They are cattled by an ambiguity of need. What is and is not offered.

Joseph’s fear was caged. Another time; a fairy tale, a Penny Story. Private box, the nurses in evening gowns, scented, hair dressed; they shade him from the eyes of the curious. Erase his attendance.

He was awed. He was enthralled. The spectacle left him speechless, so that if he was spoken to he took no heed. He often seemed to be panting for breath, thrilled by a vision that was almost beyond contemplation.

As the dancer walks among us the body of Joblard’s attention is bound to her, as with a cord. His confession has made necessary some further act. The confession is not singular; it deletes the past, recasting casual acquaintance into a darker intimacy.

She has wrapped a lizardskin coat around her shoulders, naked otherwise, the scorch of the dance contained: perfume, spiked heels. He folds paper into her cup. Gives the word; whispers. I watch the collar of this coat, glittering, in the long mirror. A snake-rope. She will come with us. They are eating Indian.

‘My dear, come along, you will be comfortable.’

‘Shit or bust,’ says Joblard, gripping his right forearm with his left hand. On the square. Dynamic tension. And another barley wine.

‘All or nothing.’

Now it is random, it is anything. My fever has cooled to a clammy chill, shirt soaked from blue to black. ‘Hinton cops out. These restraints. Whips it, fans the fire, then refuses to follow his reasoning to the death. Dementia of the monk, the self-flagellant. Vision of the snail. Unless we can exactly repeat the past, we will never make it repent; it will escape us. Nothing is exorcised. It goes on for ever.’

New weather shifts the colour of time. Concentration breaks with close thunder. A torrent. Melting skies. Bones greasy with fright. We run across the Lane. The dancer, squealing, her gleaming skin pulled tight; wobbling on absurd heels.

We are occulted: seeing the future by flashes of lightning, seeing the present from underneath.

Gull redeemed his time. When it was the hour of action, he acted. There were no instructions or whispers from secret masters: no sealed orders. A plot of ground in St Patrick’s Cemetery, Leytonstone, was unfulfilled. There were shadows: in the mortuary glass he saw the shape of the burial party. He looked across the estuary and saw the white men rising from the water: the unclaimed dead.

Читать дальше