‘Hey!’

No movement from his lips: he speaks out of his nose.

‘Yeah!’

Nods, bleary. Whistles.

‘Hey, OK. OK, man? Ha!’

Without invitation Howard starts to pull books out of the bookcase, glance at the covers, without opening any of them, crams them back, fiercely, scoring the edges, the torn lips of trout.

‘Shit! Got any decent stuff?’

Howard is like a horrible shrunken doppelgänger of Nicholas Lane; something culled from a mindless masturbatory emission. He wears a lapel badge that announces, unnecessarily, ‘BEAT DEATH’. Howard shelters within that pun.

Nicholas Lane is visibly damaged by being confronted with this mannerless futurist madman. Who considers it normal behaviour to manifest himself, unannounced, in the middle of the night for an obscure shakedown.

He is gone deep into cellular time: so vividly living the present moment that he erases history, yesterday’s books, parcels, deals no longer exist. He looks clean through Howard and the Howard behind Howard and the Howard behind that.

‘Pulled a few decent numbers, man. Elmore Leonards. You wanna come down the shop? Work something out?’

Howard’s nose is running, in anticipation. Good trade. Fix, score, shift: commodity exchange, contra usuram , let’s keep currency out of this.

‘Where he goes — I go,’ Dryfeld grunts. ‘Until we get this money split, I’m his shadow.’

Unholy twins. Waiting for surgery.

On the street they try to summon a cab. Would you take them? Two gaunt scarecrows with wild tails of rat hair; one of them bounding along, the other shuffling, as if his laces were tied; and the manic cropped Dryfeld, in despair, feeling his hair growing, actually sensing the stubble climbing out of his skull, shaking himself into a storm of bone dandruff.

The shop, in a narrow court once favoured by purveyors of curiosa , is, naturally, shut: no problem, Howard kicks the lock and the door breaks open. There’s no light, that’s been cut, but beyond the counter are two unemployable Outpatients defying their limits by the glow of a hurricane lamp.

One of them is working with sandpaper to erase the inhibiting announcement, ‘damaged stock’, from the fore-edges of a pile of bought-in publishers’ successes of last month. There’s nothing ‘damaged’ about them, except the stamp: and that is being swiftly remedied. The Outpatient’s knees are white with the flakes of falling paper. He coughs.

The second Outpatient is hunched over a kettle steaming the labels out of a collection of oversized fine art library books. If there are easier ways to earn your breakfast, he is incapable of imagining them.

The shelves in the shop, as illuminated by Dryfeld’s torch in a tunnel of unbelieving light, are rich with the direst dreck, condemned tea-chest gloom, most of the books covered in a layer of tea grains, brown, lumpy, inert. Strictly for the captive student market, yards of instant grant-bleeders.

The gelt is elsewhere.

Behind one of the stacks is a roped-off stairway that lets us down into the basement. And here the best of the Outpatients, a man whose abilities almost lift him to the rank of Scuffler, sits beside a candle, two handed, signing, with mantra-like automatism, a stack of newly minted first editions. Who would have thought that John Fowles needed to moonlight? Or that John Fowles and Dick Francis were one and the same: the left hand and the right hand.

The Ian Fleming presentations have already been taken away; to weather, overnight, under a desk lamp.

The Near-Scuffler, a former Newdigate Prize Winner, ignores us. He has seen worse things. And did not believe them either.

Dr Suk, mysterious man of business, lecturer, pornographer, liked to employ poets. He was a one man Arts Council. Liked the sense of having a court about him, the formerly great in straitened circumstances only increased his prestige: he pinched them tighter than ever, until they couldn’t move at all. Hooked them to him in talons of need; bored with themselves, blank with fear. A comfortable pond filled with the lamest of ducks. A septic tank. Each inmate able to function: but only just. Excess of energy or imagination could only harm them. Gracious Suk, the Duvalier of Shit Street.

We waited, again, a slow tongue of light, pale through the overhead grille; the fat wheels of Suk’s Mercedes block it out.

Suk looks about fifteen years old in sunshine, ninety by candle. His moonfaced benevolence, coupled with bun-sized spectacles, gave him his start: posing as the adopted child of an English Missionary to China. It was a good scam — for a while. And he played it beautifully, no hurry, easy pace.

‘Excuse me, Sir, I see that you trade in Antiquarian Literature…’ ( This to a gentleman guarding a table of tattered remnants, street sweepings .) ‘Might I have a word? Perhaps you have the time to take a cup of tea?’

Put it into print and the story screams stinking fish: but to hear him give it, the dull uninflected tones spike you, a narcoleptic nodding trance.

‘Orphan sent to Theological College in the north of England’… ( just look at the long black coat, the damp mournful face )… ‘Dear father’s books in store in the East End’… ( where? )… ‘Mostly theology and church history’… ( groan, boredom , go away)… ‘But he did also collect; er, I am not sure of the word; er-otica; very old, Sir, Japanese. How do you call them? Scrolls?’… ( the punter is drooling )… ‘You understand, I cannot myself sell such things’… ( oh no, of course, we’d look after that for you )… ‘A percentage; we could share?’… ( of course, we could; very fair; 90 per cent for us, 10 per cent for you )…

And when the hook goes in, cast according to the pretensions and potential of the punter; £30 on the street to £200 at the top…

‘To get the books out of storage now.’

It always worked. Beautiful.

The taxi eased away with one sombre bowl-faced missionary orphan.

It took about two hours per hit. He could only work an area once. Morning, Camden Passage; afternoon, Kensington Church Street; Brighton, tomorrow.

It took months to put together a reasonable roll; so he claimed a degree in Accountancy and started lecturing at night school to overseas students, who knew less than he did, but who were desperate to pick up the certificates which would allow them, in their turn, to work the game in their native lands. Awarding himself a doctorate in survival studies was easy.

Smutty videos, car repair kits, fast food, student hostels, a bookshop: with plenty of flash remaindered stock, remaindered, it must be said, without the publisher’s knowledge; an easy move from a conglomerate warehouse in the sticks. They didn’t have the remotest idea what they were holding: the computer wasn’t interested in that kind of detail.

He’d peaked: the white Mercedes, designer jeans, pigskin jacket, his own coke dealer who’d take payment in books; which would be rapidly converted back into weasel-sugar.

The stuff doesn’t come in neat plastic packets, like Miami Vice; it comes, in fast-food foil, out of the spine of a book by J. B. Priestley. A gross text, too dull for anyone to ever open. Dug out like a suppository: often it is a suppository.

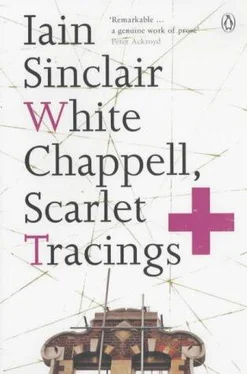

Nicholas Lane takes a carrier bag and fills it with tradables, that would never now see daylight. Stored beneath the pavement, sold at night by telephone, joined to the rest of a major collection, boxed in a bank vault. Buying just enough time to sell the big one, Study in Scarlet .

But should it be local, J. Leper-Klamm, for a quick kill? Try £8,000. Or should they call in one of the Californian fat cats, and go for top dollar, £15,000? Brain candy. Holes in the shoe.

Читать дальше