The photos on Google Street View had been taken in the early summer; the trees were leafy and the may was in bloom on the low dual carriageway bushes outside the Holiday Inn. At one point you could see right inside people’s cars. Google Street View had protected privacy by pixellating the numberplates of the cars. But at one point two cars were level at a junction and a man was in one, a woman in the other, and a lone pedestrian was waiting behind them at a bus stop. It was good to see some people coinciding, even unknowingly, just going somewhere one day, caught by a surveillance car and immortalized online (well, until Google Street View updated itself). Seeing them made me wonder briefly what was happening in their lives on the day this picture was taken. I wondered what had happened to them since. I hoped they’d been okay in the recession. I hoped they’d arrived safely wherever they were going.

Then I wondered if any of them was going to Lufthansa to complain about being charged for a ticket he or she hadn’t bought.

Of course in the end I wasn’t going to go there and explain anything. Of course it would make no difference. Of course it was impossible anyway to see anything of Lufthansa’s London Office on Google Street View since it was on a bit of the map to which the little virtual person couldn’t be dragged.

So instead I skimmed along Bath Road for a bit, first one way, then the other, until at one point the address label at the top of the photograph told me that though I was still on Bath Road I was no longer in West Drayton and that I was now in Harmondsworth.

Harmondsworth. Something inside me chimed a kind of harmony. It took me a moment, then I remembered why: Harmondsworth is the place all the old Penguin paperbacks declare their place of issue. It was where the original Penguin copies of, for instance, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which caused all the excitement and led to the obscenity trial, will have issued from in 1960, the place where the thousands of copies sold after the trial will have been issued too. And all the other Penguin Lawrences. I looked across at where L was, on my shelves. Almost all my Lawrence books were Penguin books. Pretty much all the Lawrence I’d ever read had come, one way or another, from this very place I happened to be looking at.

I stood up, pushed back my chair. I got my old copy of St Mawr / The Virgin and the Gypsy off the shelf. Oral French. I turned the page. Harmondsworth.

It was a ridiculous, glorious connection, and one that somehow made me bigger and truer than any false claim being made against me. It also made me laugh. I laughed out loud. I did a little dance round the room.

When I’d stopped, I closed the book and put it back in its place on the shelf. I stood at my desk for a moment. I reread the letter. I girded my loins. I sat down to reply.

Dear Barclaycard,

This is just to thank you and Lufthansa for the reminder that nothing in life is ever secure.

Thank you also for allowing me to find out how easy it is to be made to seem like a liar when you aren’t one.

Thank you, too, for introducing me to a whole new kind of anxiety, a burning and impotent fury which I truly believe has helped me understand, just for a moment, a sliver of what it must have felt like for a couple of writers I like very much from the first half of the twentieth century to have suffered from consumption. The experience has certainly brought a new layering of meaning to the word consumer for me.

Yours faithfully,

A. Smith.

PS. If Lufthansa ever tell you where that ticket I didn’t buy was for, just out of natural curiosity, I’d love to know.

It felt good when I wrote it.

When I read it half an hour later I knew it was too anal, like an awful comedy letter someone would send in to a consumer rights programme on Radio 4.

I deleted it.

I wrote the kind of letter I was supposed to write, in which I simply denied knowledge of the transaction Lufthansa claimed I’d made. I sealed the envelope and I put it on the hall table for recorded delivery tomorrow.

Then I went to bed, put the light out, slept.

Meanwhile, in my sleep, the freed-up me’s went wild.

They spraypainted the doors and windows of the banks, urinated daintily on the little mirror-cameras on the cash machines. They emptied the machines, threw the money on to the pavements. They stole the fattened horses out of the abattoir fields and galloped them down the high streets of all the small towns. They ignored traffic lights. They waved to surveillance. They broke into all the call centres. They sneaked up and down the liftshafts, slipped into the systems. They randomly wiped people’s debts for fun. They replaced the automaton messages with birdsong. They whispered dissent, comfort, hilarity, love, sparkling fresh unscripted human responses into the ears of the people working for a pittance answering phones for businesses whose CEOs earned thousands of times more than their workforce. They flew inside aircraft fuselages and caused turbulence on every flight taken by everyone who ever ripped anyone else off. They replaced every music track on every fraudster’s phone, iPad or iPod with Sheena Easton singing Modern Girl. They marauded into porn shoots and made the girls and women laugh. They were tough and delicate. They were winged like the seeds of sycamores. There were hundreds of them. Soon there would be thousands. They spread like mushrooms. They spread like spores. There would be no stopping them.

Meanwhile, that snake that Lawrence threw the log at disappeared long long ago into its hole unhurt, went freely about its ways, left the poem behind it.

Meanwhile, right now, the ashes of DH Lawrence could be anywhere.

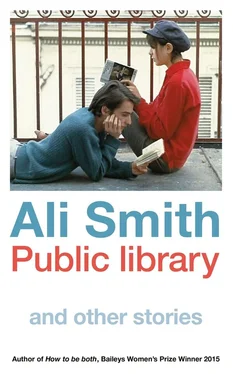

Local councils, under the pressure of draconian and politically expedient cuts, don’t like to say that the libraries they’re closing are closing. They say they’re ‘divesting’. They now call what used to be public libraries ‘community libraries’. This is an ameliorating way of saying volunteer-run and volunteer-funded.

Just in the few weeks that I’ve been ordering and re-editing these twelve stories for this book, twenty-eight libraries across the UK have come under threat of closure or passing to volunteers. Fifteen mobile libraries have also come under this same threat. That makes forty-three — in a matter of weeks.

Over the past few years, just in the time it’s taken me to write these stories, library culture has suffered unimaginably. The statistics suggest that by the time this book is published there will be one thousand fewer libraries in the UK than there were at the time I began writing the first of the stories.

This is what Lesley Bryce told me when I asked her about libraries:

The Corstorphine public library was a holy place to me. It was an old building, hushed and dim, like a church, with high windows filtering dusty light on to the massive shelves of books below. And the library had its own rituals: the precious cards (only three each), the agony of choosing, and the stamping of dates. The librarians themselves were fearsome, yet kind, allowing the child me to take out adult books, though not without raised eyebrows. My parents were readers, but we did not have many books in the house, so the library was a gateway to a wider world, a lifeline, an essential resource, a cave of wonder. Without access to the public library as a child, my world would have been smaller, and infinitely less rich. All those riches, freely available, to everyone and anyone with a library card. All children should be so lucky.

There’s a great kids’ library at the end of our street now where we live, in Notting Hill, soon to be sold, along with the adult one, though they claim to be rehousing it nearby.

Читать дальше